As part of the 10th anniversary of The Savage Critic on the web, and since we had such a great time last year doing it with WILSON, we've decided to try and do several Savage Symposiums this year, leading with one "mainstream" and one "alternative" title. Abhay is leading the superhero one, which should see print in about two weeks, and I ended up leading this one, for Chester Brown's PAYING FOR IT.

I asked the gang five questions, the first two of which are presented here for your reading pleasure. A question a day will follow through Friday.

Since we didn't know what our reactions would be until after the book (s) were released, I found that I wasn't a huge fan of PFI, and my questions are generally pretty bitchy. That said, I think you'll find this to be fun reading.

I suck REALLY hard because I've got no art for this, and if I have to go find some (or, more likely, scan it myself) this won't get up for another few weeks...

Anyway, enough preamble, let's get to it!

Question 1: Memoir Versus Polemic. PAYING FOR IT is subtitled as “A Comic-Strip Memoir About Being A John”, but I actually wonder how much you found that to be true? Perhaps this is an issue of definitions, but (to me) a “memoir” doesn’t try to lead one to a point. I think that it is true that memoirs don’t need to be as strictly honest as one expects of an autobiography (or as Will Rogers said, “Memoirs means when you put down the good things you ought to have done and leave out the bad ones you did do”), but PAYING FOR IT strikes me much more as a constructed argument that attempts to use the autobiographical form, than a memoir in and of itself. Plus, it pretty much cuts away right when it gets to what I felt was the most interesting point of the memoir -- how does a monogamous paid relationship actually work? Anyway, am I splitting hairs here? Does it succeed as a memoir? Does it succeed as a polemic?

JEFF: A good set of questions here, Bri, and I think it’s not that you’re splitting hairs with the book so much as trying to [and hopefully this will be my only exasperating pun] find a convenient hole to put it in.

Certainly, Will Rogers’ definition of a memoir doesn’t jibe with the current use of the term and hasn’t for at least a decade, if not longer. In fact, it’s probably more true to define today’s memoir as exactly the inverse: the memoir is the refuge of drug addicts and alcoholics, adulterers and participants in incestuous relationships, crooked cops, career cheats, wastrels, rakes, and -- worst of all -- writers with literary ambitions.

But just because your definition is outdated doesn’t mean you’re wrong. One of the many, many problematic aspects of PAYING FOR IT is that it’s neither one or the other. It’s a memoir and it’s a polemic, and it’s not just an argument for the legalization of unlicensed sex work, but it’s also an argument against monogamy and romantic love, to boot. (And based on how Chester Brown draws himself, you could also imagine it’s the weirdest Mr. X story ever told, but maybe only I did that.)

PAYING FOR IT is like Thoreau’s Walden except with blow jobs instead of trees, and Walden generally doesn’t get dinged for mixing its autobiographical elements with its polemic ones. I think PAYING FOR IT’s failures (and its successes) transcend whether it works as a memoir or a polemic. As you point out below, Brown’s admissions and adherence to his definition of a memoir end up puncturing some of his most crucial arguments. But what appears to be your take on the book -- “PAYING FOR IT is a polemic, and a bad one because the things Brown shows contradict his points” -- show an impressive lack of generosity toward the creator. Maybe it’s a bad polemic because it’s not supposed to be a polemic?

But then, that does beg the question -- what the fuck is this book, anyway? Having that question unresolved makes this book absurdly hard to write about in more than the most superficial way. I hope I can get a better take on what it might be and how it functions as we proceed.

I will say this, though: PAYING FOR IT has given me a lot to think about and I think that makes it, at the very least, a “not-failure.”

ABHAY: I don’t think I read enough memoirs to have strong “genre expectations” where they’re concerned. I think it succeeded for me as a memoir-- just maybe not one concerning prostitution. For me, it’s a story about this guy, growing old alone, alone except for some equally, uh, “eccentric” artist friends, and his desperate need to rationalize to them something unusual he finds that makes him happy, however little they seem to care. He can’t accept just being a quote-unquote “bad person,” or accept that Joe Matt’s stepmother judges him, or simply keep his personal life to himself—the story is his struggle to make what he’s doing not only acceptable, but “right”, morally correct, until at the end, he’s “succeeded” and reasoned & rationalized & pontificated his way to something almost resembling a happy ending. As a story about prostitution, I’m not sure if it meant much to me. But as a story about people’s need for acceptance, just to be accepted as you grow older, maybe about friendship—looked at that way, I suppose that I think it succeeds quite a bit. I think it’s a very sad comic, though. I don’t know that it succeeds in a way that Brown intended, to the extent that matters.

So, I think I differ with most of the reviews I’ve seen in that I think cutting away from the “most interesting point” was the best choice Brown made. I’m not sure if this is intentional or not by Brown but... by doing so, he presents this relationship with this woman he “loves” as being secondary to telling Seth about it. I think it’s a more meaningful and telling detail that we saw THAT instead of him expressing his love directly to his employee.

(I don’t know. It’s that weird thing with memoirs where… are we supposed to judge his life? He’s selling his life. But I know people get queasy about that sort of thing, and heck, I suppose I do too…)

As a polemic though, I’d suggest it’s a failure. But come on: how many people are really buying this comic with an open mind? Political art in general for me-- there’s always that thing of “congratulations on blowing the minds of the well-meaning liberals trying to impress one another with how cool & laid back they are.” Still—he’s debating Joe Matt and Seth…? Clarence Darrow’s not really breaking a sweat with those two, by the looks of things. To succeed as a polemic, Brown would have had to have engaged with the world around him, and talked to educated, engaged people with differing viewpoints on the issues, instead of beating-up on straw men. He’d have to have been Joe Sacco, instead of drawing himself lecturing Seth. Plus: Brown presents himself as being a broken weirdo riding a bicycle. I don’t think it really challenges reader’s prejudices to find out that broken weirdos bicycle to-and-fro brothels. (That absurd scene of Seth telling Brown to “get a girlfriend” – sure, sure, there are probably acres of Canadian women, waiting for a hoser with a Schwinn ten-speed to pedal into their lives.) While it’s perhaps true that odd guys like prostitutes, it’s certainly been my experience that way, way more guys than fit that description have paid for sex, just thinking of people I’ve known or met, friends of friends, etc. I’ve known a wide range of guy-- most of whom I’d call “decent” and “normal”-- who’ve paid for sexual encounters, and none of them have been like Chester Brown. Hell, it’s been ALL of our experiences, thanks to Tiger Woods. Eliot Spitzer. Hugh Grant. Etc. I think Chester Brown damaged his case by virtue of being Chester Brown...? Maybe that’s cruel, though.

TUCKER: I thought it succeeded as a memoir under the most basic “googled a definition of the word” rules. This is some stuff Chester Brown did, some conversations he remembers having, and his personal beliefs on the subject of prostitution. That’s enough for it to be a memoir, in my book. I’m inclined to agree with Abhay in that I think this story ends up being a lot more about the fact that Chester Brown has some unusual and unpopular beliefs that end up making this a memoir more about how Chester might be a pretty unusual person than it does a book about prostitution or any other subject he might have planned on. I’m going to forget about the appendix and remember Seth calling him a robot, basically.

On the question of whether its a polemic or not--I can see where people might say that it is in terms of the way Chester presents his belief system, but I just can’t take it seriously, and I’ll just go ahead and say that I find it absurd that anyone else would do so. The appendix to the book reads like one of those 9/11 truther websites, only this is about why human trafficking isn’t that bad because Chester underlines the word “want” in the phrase “they want to be trafficked”, and the hits go on from there. I wasn’t totally surprised by the junior high school library card essay club nature of the notes half in the back--by the time I’d gotten there, I’d already seen the way Chester “debated” these subjects with his friends--but I was still a bit surprised at how much effort seems to have been put into presenting a dilettante's attempt at rationalizing his behavior as if it were on the same level as a Pulitzer winning investigative team. Early on, Chester shoots down a perfectly good argument from Seth (in the Odysseus/romantic love discussion) by asking if Seth has any stories to back it up. When Seth says “if there is one, I don’t remember it”, Chester chooses to use Seth’s lack of proof AS proof...for the Chester Brown point of view. That’s the kind of “argument” going on here, and while I’ve got zero problems with that as local color for a memoir, and would go so far as to say that re-reading all of the Seth scenes alongside Seth’s own appendix makes it an even better memoir, it’s one of the main reasons that I don’t see any reason why someone would engage with this thing as a political animal. I’d point anyone towards Seth’s own words who argues differently.

CHRIS: I'm going to bypass everyone else's definitions of memoir and look at PAYING FOR IT based on what I assume is the reader's expectation for any memoir, be it a conquering hero's victory lap, the confession of a scandalized figure, or Some Quirky Person's Quirky Story: to get some insight on the subject of the memoir.

On that level, PAYING FOR IT didn't work for me as a memoir. I knew going in that Chester Brown was a Canadian cartoonist that championed the patronization of sex workers over monogamous romance. I knew he was friends with Seth and Joe Matt, and that he used to date that lady from MuchMusic. I think I even knew he was a libertarian. If the reader didn't know any of that, they can read the dust jacket of the book or skim his concise Wikpedia entry.

Brown's decision to minimize any aspects of his life that didn't involve being a john is understandable, if frustrating. Like Abhay, I think his conversations with Matt and Seth were the most illuminating and engaging narrative spine. But to structure the book as essentially a catalog of all his paid orgasms, and then seemingly take pains to genericize all but the Yelp Review-iest portions of said orgasms made large stretches of the book a slog for me. For an act that he posits is so 'sacred', he might as well have written a 'memoir' about all of the times in the past eight years that he's scored cocaine, or shoplifted a book, or shit in someone's hat. Actually, I bet all of those would have more variety in their telling. Unless of course Brown decided that to 'protect' others that he would draw all of the hats as a Seth-style fedora, and change the names of the stolen books.

As a polemic, it succeeded in feeling like a polemic. But I had the same reaction as Tucker to the level of argumentation. It didn't help that a few years ago I read Against Love: A Polemic -- at the behest of a Canadian girl, now that I think of it, what's with Canadians? -- and it covered much of the same ground, except it was written by a college professor who understands how to argue and cite resources. I didn't find it any more compelling than Seth's argument, but I could at least admire the structure.

*********************************************************

Question 2: Entertainment Versus Argument. I’m not certain that I’ve read anything much like PAYING FOR IT before, primarily because I think that it mostly functions as an argument above all else. This isn’t why I, as an individual, read comics (or, for that matter, consume most other media) -- it isn’t that all work would need to be fiction, but more that non-fiction work should either be properly objective (like, say, LOUIS RIEL) or “entertaining” (like, say PYONGYANG or even PERSEPOLIS). Even in cases where it’s clear that the author has a clear point of view on what they are discussing (say, MAUS), I expect to be “entertained” by the story. Does this make me a obnoxious reader? Is this expectation fair to the work, and were YOU entertained by it? For me, I really flashed back to CEREBUS #186 more than anything else, and thought “am I supposed to be enjoying spending my time with this?” I can’t ever imagine reading this again, whereas I go back to my first four examples on a fairly regular basis.

JEFF: Aughhhhhh! Can I just say that for a moment, here? Aughhhhh!

I think your questions do a fantastic job of laying down a framework for discussing the book, B, but I’m finding myself reacting more to your framework than to the book itself. Let’s just say that there are three levels of struggle going on with me here: (1) I’m struggling with whether your very common-sense definitions are inappropriate just for this book, or for art in general; (2) I’m struggling with how to define PAYING FOR IT, which is great at resisting classification and terrible at accepting it; and (3) I’m struggling with whether I can consider the book a success even if I decide it fails at what I decide it’s trying to do.

Whether or not entertainment was PAYING FOR IT’s intent, I was entertained by this book. I was entertained by how Chester Brown looked like Mr. X. I was entertained by how much Joe Matt came off as selfish, insecure, more than a little weaselly, and yet still fully rounded as a character. I was especially entertained by Appendix 3, in which Chester Brown creates the world’s worst argument for prostitution by imagining a future in which everyone has sex with anyone they don’t find abhorrent as long as they are paid -- it was like reading a Jack T. Chick tract from Bizarro Earth! I was entertained by CB’s drawing of himself in tighty-whities. I was entertained by the time I spent trying to imagine how Brown might score on tests for mild autism. I was entertained by the idea Brown thinks he knows the lives of sex workers because he’s been a john, and how that might be similar/dissimilar to the way viewers might think they know the life of a creator because they’ve beheld their art.

Entertainment isn’t the right word in many cases here. Maybe it’s something like “engagement”? For example, I’m reluctant to say I was “entertained” by the scene in which Brown admits to being turned on by the woman who keeps saying “ow!” while he has sex with her -- but I’d be lying if I didn’t say I was...I dunno, enthralled? Trying to figure out why Brown would admit such a thing took up a certain amount of active thought, you know what I mean? Is Brown trying to portray himself in a neutral light? A positive light? Is he trying to play “fair” with the reader? Was he totally unaware of how dehumanizing it is to portray every sex worker as faceless?

For that matter, why does he think someone will recognize a sex worker’s face from a caricature? Why does he think he can’t create new faces, new names? Why does he tell us he drew “their bodies accurately, or as accurately as my memory allows”? If Brown sees sex “as sacred and potentially spiritual” (as he tells us in Appendix 15), why does he remove every emotional component from his sexual encounters? Why does Brown have a nimbus of light in many of his panels, but not others? Why does every sexual encounter have that nimbus? Is that his definition of the spiritual? Why does that book end with the picture of Brown? Why did I shudder when I saw it?

These considerations don’t “entertain” me, but I find them engaging as hell. And I feel a certain appreciation for Brown for allowing me to consider these things because he stays so true to...whatever the hell he’s staying true to. Because he stays true to it, I’m able to come to some conclusions I wouldn’t have been able to if Brown had been more willing to manipulate me or prevaricate.

ABHAY: I think I’d classify it as a “personal essay.” Those are pretty common.

I don’t know if I’d call PAYING FOR IT “entertaining”, but I’m not sure if we all have the same definition of that term. (Especially as I’m not a PERSEPOLIS fan). But it’s a provocative piece of work, and maybe that has its place, too. I think it’s more provocative and suggests more for the reader to think about than a number of the other comic memoirs I’ve read (e.g. FUN HOME, say)-- and so I would think at least some select audiences would find it “entertaining,” by virtue of that fact. There were a few pages where I was creeped-out by what he was showing or the fact he’d made the comic at all, namely page 1 to the final page that I read. I think I had the same reaction as Jeff to the author photo. I went “UGH” or “YIKES” a couple times out loud. Whether that’s “entertaining,” or we need a different word for it, I don’t know, but I have no regrets. (Seth’s line about Brown & Joe Matt was certainly funny). My reaction to most comics is “What were they even trying to do? Why did they even bother? Why is this taking place at an AA meeting?” So, I prefer being skeeved-out to feeling nothing. And I definitely got to feel skeeved-out lots and lots, so.

And heck, some of the jokes were funny—I certainly hope that Brown bicycling away from his “conquests” was meant to be humor, at least. Enough of it was funny to me that I guess I took the non-lecture chunks to be intentional black comedy and not something unintentional. Though, I thought there was some fine unintentional comedy, too. You know, part of the comedy of PAYING FOR IT for me is that Brown’s looking at the rest of the world, saying “Look at how crazy all these OTHER assholes are.” I think that’s fucking hilarious. It’s funny for me that Brown can’t abandon his need to judge the rest of the world, no matter how shitty his life gets-- the Good Lord knows that’s the road I’m on, so here’s to the good life! Did Brown intend it as a comedy, that the ultimate endpoint of the world-view expressed in alternative comics is a bald man thinking the rest of the world is crazy while he grunts over his imported sex slave hiding her face with her hair so she doesn’t have to see the skeletal rictus he calls an O-Face? Maybe not. I don’t know. Is it technically comedy when you’re the only one laughing? I don’t know. I don’t know. Are we supposed to judge his life? Here we are.

I don’t think I’m interested enough in the subject matter to have sought it out for myself if we weren’t doing this. There’s an old Dennis Miller line, back before he became so awful— something like “The most interesting thing in the world to me is my orgasm, and the least interesting thing in the world to me is your orgasm.” You know, I bought the Winshluss PINOCCHIO the same week—I’m much more taken by that. I thought that was significantly, significantly more impressive.

Since I didn’t need persuading on the issue of prostitution-- I’m basically okay with whatever people want to do—for me, it’s nothing I’m especially excited about because the book didn’t add to much more than an exercise in “Look at me.” Maybe that’s true of all memoirs; I’m just not a memoir guy-- I’m too self-centered. I get my “Look at me” needs filled quite sufficiently by the internet. This comic would be very impressive if the internet doesn’t exist—but as it does... You can read the diaries of a prostitute at the McSweeneys site, not exactly a hotbed of lasciviousness—discussion of such things is not particularly hidden from view or noteworthy. And the act of an artist revealing something startling and unseemly about their lifestyles for their commercial gain—shit, I don’t know why anyone would find that very surprising. I suppose these things are rare for comics but … so is intelligence, wit, craft, not-hating-women-constantly, charm, originality—shit, once we start making that list, we’ll be here all fucking day. And-- and I don’t know. I’m rambling. Sorry. So, in conclusion, I think Frank Miller said it best when he said, “Whores.”

TUCKER: It’s probably worth mentioning that I only read and decided to participate in this questionnaire after reading Abhay’s above response.

BRIAN: And I just want to jump back in here and second that Winshluss PINOCCHIO recommendation...

TUCKER: Lemme third that one for you. That Pinocchio book is incredible.

*********************************************************

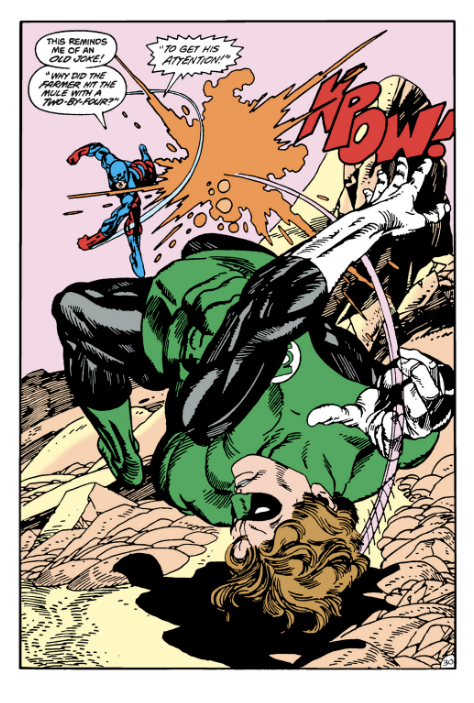

They had me at "Kpow!": Gil Kane Atom slugs Gil Kane Green Lantern, from Justice League of America #200.

They had me at "Kpow!": Gil Kane Atom slugs Gil Kane Green Lantern, from Justice League of America #200.