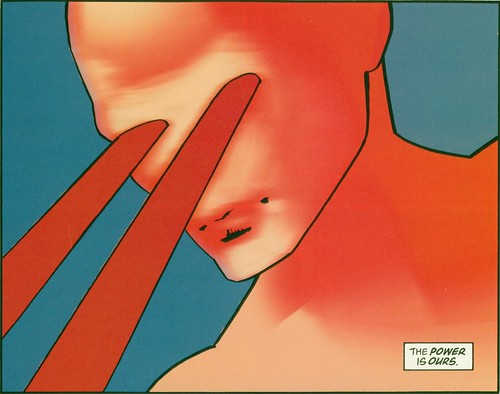

SAVAGE SYMPOSIUM: WILSON by DAN CLOWES

/Dan Clowes is the cartoonist and author of a considerable number of the most celebrated comics of the past 20 years, including GHOST WORLD, DAVID BORING, ICE HAVEN and THE DEATH RAY, all of which originated in his EIGHTBALL anthology series. His most recent publication is WILSON, his first original graphic novel published by DRAWN & QUARTERLY and released on April 28, 2010.

WILSON prompted the following Savage Critic round-table discussion, which took place via the internet between May 2 and May 9, 2010.

ABHAY: Let's start with the premise. WILSON is a series of one-page comics (mostly, gag comics) documenting the life of an abrasive Clowes-character, between late-middle-age and old age. Wilson is a hyper-critical blowhard with a persistent need to expound at length upon his opinions to total strangers, whose relentless judgments on everything around him-- none really earned by a life of any notable accomplishment-- leaves him increasingly isolated and pathetic. So, question #1: Is Dan Clowes making fun of me? What did I ever do to Dan Clowes?? We all fall under the category of "internet loudmouths", as far as St. Peter is concerned, so: did you relate to the Wilson character? I'm curious to know how much your sympathy for the main character, and/or recognition of yourself in the main character, impacted your enjoyment of the book. That seemed to be the thesis of Mr. Glen Weldon's WILSON review for NPR. Weldon's review suggested the pleasure of WILSON was recognizing the worst parts of yourself in the main character. And I think I had the opposite experience, where-- I read it on a night where I was having a little struggle with the ol' self-esteem, and WILSON provided the precise opposite of relief. I had a "Why did I just do THAT to myself" reaction to it, a wrong-night-to-read-Clowes reaction, on a pure human level, separate and apart from any admiration of craft or what have you. How did it find you?

JOG: Speaking from my personal experience, Wilson is a nearly-to-a-T reminder of one of my uncles, since passed; we weren't super-close, but I liked him a good deal, we got along well, I think. He carried himself in much the same way, albeit without Wilson's incessant, possibly fake nostalgia for a time when people really connected to others. Or his prolonged unemployment, or his failed marriage; like, this guy I knew was a consistent worker, very pragmatic, who essentially understood the disconnects between people - then again, maybe Wilson himself is like that, just not on the page? In that his sputtering seems characterized as only half self-aware? I'm thinking of the various bits where Clowes has Wilson going off and yammering toward the end of a page, while his unwitting target just sits there resigned to their fate - it got so that sometimes I wondered if Wilson was even actually talking or if several of his rants are simply occurring in his imagination. I don't know if that's correct as in-story happenings -- a bunch of the time people WILL react to Wilson, so that would render the technique odd and irregular, not that Clowes might not be interested in that anyway -- but it does isolate Wilson as a real oddball purely by his impolitic nature, rather than for his yearning for a more pressed-flesh kinda existence. Obviously one of the big running gags is that Wilson is a "people person" who completely fucking hates people, because they don't meet his standard of how people should interact, which naturally implies (to me) that Wilson doesn't understand his own outlook all that well.

As for the effect it had on my reading, I'd say I found it more difficult to process the book as 'pure' humor, which I know is how some people took it, in that it struck me as more of a painful, seriocomic character study. And it's not just personal recognition feeding into that -- most of the comedy-of-awkwardness Clowes is dishing out is very similar to the humor in Chris Ware's work, where I think it comes off better (just done better, better timed, written; funnier), and anyway some of the page ending 'gags' are straightforward, pretty cheesy dramatic beats (I'm thinking of the part where he asks his dad on the phone if he's been to see the doctor, that'd be the earliest manifestation of that) -- but I do wonder if the farcical aspect of the character would be clearer to someone who might interpret it all as some distillation of the worst part of themselves, rather than a fairly recognizable personality type? I mean, I agree that parts of Wilson's struggle are supposed to be taken as a variation on universal human longing, judging from his cliché attempts to divine meaning from water and weather patterns, which are acknowledged by the character as being a silly banality, but of course Wilson is a silly character, so in the end it's raindrops beating rhapsodically on the windowpane that leaves him touching something he believes to be divine, so it's more of a look-how-true-and-lovely-these-well-worn-poetic-devices-really-are. This is immediately preceded by a defiant howl of existence against the uncaring universe, again ironically positioned because it's really an empty cafe, ha ha, not the universe (and the one other guy in there would probably like to leave since Wilson is really annoying), but - it's a lot like a genre comic acknowledging an overused trope before using it. That doesn't make the writing deeper, it just indicates the writer knows better and did it anyway.

Er, to sum up, it strikes me as a fairly natural impulse on a reader's part to want to identify with a nasty character by recognizing said nasty parts in their own personality, but I don't think that's entirely the point here; I saw Wilson as a pretty specific, wholly-formed character in his own right. Moreover, my idea of the book's visual concept is that Wilson is a singular character -- "100% Wilsonesque" as the back cover puts it -- that perseveres within and according to himself, while the reader's observational position is aggravated by ever-changing visual styles that I think inevitably color our reading of the action.

TUCKER: Near the end, Wilson refers to Thomas The Tank Engine as Thomas the Train Engine, and I did that once too.

SEAN: I don't think I recognized myself in Wilson any more or less than I recognize myself in any character I read about. You can't help but pivot off of shared experience, and so to the extent that I've ever thought "Jesus Christ what a miserable fucking shithole this world is" then yes, Wilson and I have that in common. But at the same time I can't imagine being abusively rude to total strangers I met on the street or in a cab or coffee house or whatever. (The Internet, on the other hand? Game on, assholes!)

DOUGLAS: Wilson came off as a blowhard and a dick every step of the way to me--an absolute jerk who likes to pretend he wants to connect with other people but can't begin to manage it. He's always a caricature, and I never really believed in him because of it (I can't imagine, for instance, why Pippi got married to him in the first place). The routine of his trying to find meaning in nature had its moments, though--I like pg. 58, "Icicle," although it reminded me a little of Jaime Hernandez's story in Kramers Ergot 7 ("I still don't see it").

SEAN: Douglas--well, Pippi was clearly a mess herself, right? Compared to a situation where getting a tattoo that reads "PROPERTY OF SIR D.A.D.D.Y. BIG-DICK" is the right choice, marrying Wilson doesn't seem so bad. Of course, if you don't buy Wilson, you might not buy Pippi either.

BRIAN: There wasn't anything in Wilson himself that I saw or didn't see in myself, I wouldn't say -- but that's generally true for Clowes' characters for me. I tend to think that Clowes most vivid characters, in general, are obsessed with being right, even when they're clearly wrong. Hm, actually, on reflection, that does sound a bit like me after all...

DOUGLAS: Note the Washington City Paper interview with Clowes: "Likable characters are for weak-minded narcissists. I much prefer the Rupert Pupkins and Larry Davids and Scotty Fergusons as my leading men." Fair enough; but if you've got a totally abrasive deadbeat as your lead, it's hard to justify claiming that he can function in society without showing us how.

CHRIS: Wilson definitely fit the Larry David archetype for me: a protagonist in a story in which you more readily identify with his many victims. Still, like with most unlikable characters in fiction, I found myself cringing with brief flashes of identification. Then again, I'm the type of person who will suddenly remember a shitty thing I did to another kid in sixth grade, and spend the rest of the walk home feeling like the world's biggest jerk. I don't think that identification or lack thereof affected my enjoyment of the book, for better or worse.

ABHAY: Like Clowes' DEATH RAY, WILSON leaves a lot of information off-panel, and on re-reading it for this, I was struck by what he chose to leave off-panel. Namely: Wilson has friends. Page 30's Long Distance, possibly Page 67's Housemates, and Page 70's Caller I.D. all involve Wilson on a phone or receiving phone calls from other people in his life that we never see. By leaving them off-panel, has Clowes inherently made a statement about friendship, that "friendship is meaningless compared to family"? Such a statement would strike me as notable. Statistics and demographics will tell you that people are marrying later in life, starting families later in life, relying on having friends more. On the other hand, I know I can be pretty cynical about "friendship"-- there's a lot of dull comics about how "being friends means something, dammit!" What do you make of it?

JOG: Ha, I took page 67 just as Wilson describes it: that's he's managed to harangue some hapless insurance salesman into a conversation about his life, which is perfectly in keeping with his characterization throughout the book, although I guess he could just be taking a preventative measure against Shelley talking to him. It's all much more humiliating if it really is a random stranger, though, and anyway the joke seems to be that Wilson isn't very intimate with his housemate, no doubt due in part to his unconsciously abrasive nature as demonstrated for us.

I think the idea of family becomes more pronounced than friendship because the story is in large part about Wilson's mostly crappy attempts to communicate with people -- it's stated on the first page, and it's the engine of most of the gags, Wilson attempting to chat with folks and failing horribly -- and he seems to value this face-to-face ideal of human understanding that flatters the notion of family. Those are people you should always be able to talk to, and extract wisdom from, as Wilson understands it, given his remarks about wanting to record his father's story, so the story of Wilson pivots dramatically around his even-worse failings regarding family. I also take the absence of Wilson's acquaintances as another means of keeping the reader in a particularly observational state, really peering at Wilson so that we only ever see him and his purportedly bottomless appetite for the most profound communication, generally failing, so that "friends" and accidental encounters are pretty much the same in terms of demeanor. I liked how the prostitute gets more than one page, since she's at least getting paid to hang around with this oaf, and I guess sex mandates a little more attention than average.

The big irony of the book is that Wilson is an egoist, and, through the dozens of refracted impressions that are Clowes' ever-shifting art, the book forces the reader to examine Wilson from all sorts of angles, even though he can't know or benefit from that, and the final impact is that he remains the same as a character. We never discover what he realizes about life in the end - the book makes it a point to conclude right there, so we're not being placed in the position of God, let's not get cocky. That's only Dan Clowes.

SEAN: Well, Wilson's family relationships are pretty meaningless, too. He starts off estranged from his ex-wife, with a daughter he's never met, and a father he barely speaks to. He ends up estranged from his ex-wife, with a grandchild he's never met, a daughter who notifies him of this grandchild's existence essentially out of a sense of obligation, and a dead father. In between, he goes to prison for his forced rapprochement with his ex and daughter. I see his sudden seizure on the concept of THE FAMILY as part of his generalized fallen-world lionization of various hoary old conceptions of how society is supposed to work, but he's no more able to actualize this than he is to carry on a normal conversation with anyone. Seen in that light, whether he has or doesn't have friends doesn't matter much.

DOUGLAS: Also, this is coming from Dan Clowes, whose Ghost World is one of the great American comics about friendship (among other things). But I think showing Wilson and his friends on-panel together would have required him to make more of a case for the kinds of meaningful connections Wilson is capable of forming with people, which wouldn't make a lot of sense in the context of this story.

BRIAN: Nah, I think you're over thinking it, Abhay. I mean Wilson is about Wilson -- even when he's trying to engage with family, he's never concerned with anything that isn't about him. Hell, look at "Fatherhood" or "Grandfather" or even more so, "The Trail". The few places where Wilson engages with other people outside of his family ("friends" or not) his behavior doesn't change. I think Clowes showed all he needed to of friendship to make the point.

CHRIS: Wilson seemingly tries to befriend everyone he meets, in his own broken way. The fact that "friendship" to him is someone who will listen to him monologue about himself and how everyone else is an asshole, which is presumably why he has so few friends, and why the interactions we do see end so poorly. I'm sure he's met some people who will put up with repeat performances for whatever reason -- maybe because in Clowes's words he's the sort of guy who is "fun to hang out with in short and finite increments", though none of us seemed to have that experience in our short finite increments of interaction with him. Perhaps there was once a less-Wilsonesque Wilson, the same man that somehow managed to court Pippi and (presumably) have some sort of childhood to look back fondly on. Or maybe not, maybe Wilson has always been a terrible person and his friends are equally terrible. I don't know that Wilson cares any more about "family" than he does about "friends" -- if anything, "family" is just a subgroup of friends who he thinks should feel more obligated to put up with all his bullshit. That doesn't lionize or impugn "friends" or "family" as concepts external to Wilson, just for him. And what else matters, he might ask.

DAVID: The thing about leaving things "off-panel" in Wilson is that the book doesn't just have gutters between the panels, it has gutters between the pages - supergutters. Wilson's structure as a series of discrete one-page comic-strip vignettes leads to Clowes having the ability to, by reordering the pages (something he's said he's done), change the pacing of the story. The best example I can think of this is once Wilson goes on what seems to be a totally blissful family trip with Pippi and his daughter, and then, a few pages later, there's a strip revealing the fact that both Pippi and his daughter were straight-up kidnapped. Clowes doesn't show this moment, and this makes those initial vacation strips that much funnier: "How the hell did this asshole get an actual family vacation?" I imagine he uses the same sort of tactics on whatever friends he has, likely trapping them in his orbit by inducing guilt.

ABHAY: Jog, in his review over at Comics Comics, refers to WILSON being a "a worthwhile experiment, and sometimes a trying, tedious one, particularly as the comedy [...] gives way to a wholly expected whiff of fleeting redemption." Did you find the ending predictable? Or do you find the comic thematically, I don't know-- too simple? Is the comic saying more for you than "live a decent life, otherwise you'll be sad you don't know your grandchildren"? I know some of you are pretty punk rock-- is that too bourgeois for you punkers? What are you even rebelling against, punkers? Is all the formatting Clowes does tarting up 5-cent middle-class values? Or do you think it's a more honest comedy about a misanthrope than is normally the case, e.g., the end of AS GOOD AS IT GETS where the Jack Nicholson misanthrope ends up with Helen Hunt. (As comedies about chubby misanthropes go, I like the BANK DICK more...) I don't know. I'm a quiet person, an introvert, a bookworm, quote-unquote "sexual dynamite", so as a quiet person, a story about how a loudmouth suffers in life... That doesn't really conform to how I view the world, I guess. What do you think of WILSON's themes?

I disagree with your description of him as well. He's a loudmouth, maybe, but he's very much a quiet person, he's an introvert, he's a classic bookworm, he's all those things. There's very few scenes in there where he's dealing with more than one person at a time, and there's never a lot of stuff where he's doing more than throwing out verbal shitbombs, he rarely actually responds to being corrected or told he's wrong. Part of that is the punchline-dependent delivery, the way Clowes doesn't ever play the scenes out after the final cymbal crash, but I don't see Wilson as a truly confrontational misanthrope, mostly because I don't see the evidence for him being one. He can throw a punch, I don't disagree, but he reads like someone who just throws one and then hurry off to be alone and continue the conversation in his head, where he's certain to win.

JOG: Interestingly, the two-page side-story Clowes did in the New Yorker was, in fact, one scene over two pages, making it twice as long as any sustained scene in the book proper, and it does feature Wilson dealing with multiple parties at once. He comes off much more clearly as a loudmouth in those pages, if only because Clowes lets the scene play a little while longer, apocryphal as it might be in the grand Wilson narrative. I prefer the elusive quality of the one-page-only concept, which I think bolsters the flux status of the art.

I'm hesitant to break the 'story' and 'art' portions of the work too far apart, because their interrelation is so necessary to the whole experiment; I totally agree that the themes inherent to Wilson's characterization are simple, but there is more going on than Clowes running through these routines in the form of a comic, he's seeking to optimize them in comics form, i.e. using the miscellany of diverse visual impacts to emphasize the subjectivity of observation. Here we see reflective Wilson, in a lamp-lit world of silhouette. Now he's a big-nosed cartoon blithely revealing his fantasies about his ex-wife falling into ruin. Now he's a realist human figure, reflecting while his lover is sleeping, eventually discovering the chill shade of SIR D.A.D.D.Y. BIG-DICK. Sometimes this approach is facilitative of whatever narrative the current page is trying to deliver, but it primarily underlines the structure of Wilson's life -- as in, the thing he denies on the book's penultimate page -- even if it's only a structure we can see, as observers. Wilson remains inside himself, forever oblivious; this is the most universally-keyed impact in all of the work, because none of us can glimpse that structure as it pertains to ourselves. All of us are therefore Wilson, in addition to Wilson being Wilson and ourselves being everyone else - the blend of elements that forms a comic is what assures us.

The problem is, while Clowes' usage is very present, it's not especially rich. Page by page, the 'gag' setup facilitates a simplistic pace, a boom-boom-boom of similar beats at the end of most of the book's vignettes, which leaves the serious parts feeling mawkish from repetition. It compares poorly to Clowes' more varied use of the multi-strip technique in Ice Haven, which encompasses a plurality of narrative modes along with the shifting visuals, or something like Jason's Hey, Wait..., which relies on an even more rigid six-panel grid format, one vignette per page, yet doesn't feel the need to emphasize some particular beat on every page. (I mean, I suppose the approach inevitably forces discreet focus on every page, but Clowes really seems to push the impact of each section, to the point where I found myself thinking "ooh, here comes a serious part" a few panels ahead of the story, which isn't a helpful thing when you're dealing with so simple a plot.)

SEAN: I don't see any redemption here, fleeting or otherwise.

JOG: Oh, he's not entirely redeemed in the eyes of any of his fellow characters, although his daughter is certainly willing to humor his desire for familial connection through the internet, and Shelley appears prepared to put up with his shit for a while; her last page in the book sees one of her hands momentarily touching Wilson's shoulder as he begins to weep, though (of course!) he doesn't notice. But, importantly, the narrative affords him climax - his Thomas the Train Engine tears lead right into his shout of existence leading directly to his critical epiphany of raindrops. Then: whiteness. Clowes cuts off the narrative, so that Wilson is left in a state of grace. Obviously it could change in the very next second, as it could for any character experiencing any concluding epiphany, but what we're left with is a more (I dare say) romantic character who finally Understands Things. That's the redemption, via structure. Again, the very thing Wilson denies existing on the penultimate page.

DOUGLAS: I found the ending pretty irritating too, but I also can't think of a way to wrap up the story that might have been more dramatically satisfying. (Thought experiment #1: what if the last page before the whiteout/"death" were Wilson looking at the rain and saying "I still don't see it," a la that Jaime H. story? That wouldn't really work either.) I agree with Jog that the multiplicity of perspectives/techniques doesn't amount to much, because we never get a look at Wilson that makes us see him particularly differently. (Somehow I keep thinking of the Christmas special of the British version of The Office, where we see David Brent hitting it off with Carol and it's suddenly evident that exactly the same traits that make him the unbearable boss we've seen for the rest of the series could potentially make him a fun boyfriend.) Maybe that lack of redemption, or of the possibility of redemption, or of any particular kind of change in the protagonist, is a systemic problem here--it's a story about how Wilson stays exactly the same, and that means it has to be a series of events strung together until the clock/number of heartbeats/page count runs out. (Because every single comic book has to be exactly like Joseph Campbell's Hero's Journey, that's why!)

SEAN: The ending reminded me of a cross between the ending of The Godfather Part II and that episode in the final season of The Sopranos when Tony does mushrooms in the desert outside Vegas and yells "I get it! I get it!" to the rising sun, then changes absolutely nothing about his life. I don't see sitting by yourself having some sort of revelation about life but sharing it only with yourself and perhaps the rain on the windowpane as any kind of state of grace. What's weird to me here is that Jog and Douglas seem to agree that the ending is lackluster, but don't actually agree about what the ending constitutes, unless I'm misreading something...

BRIAN: As a technical piece of work, I thought the format worked beautifully -- at first it seems as though you're just reading a series of one-page gags, but then it turns to where you see that they're actually adding up to something. As a reader, I was feeling pretty "OK, I get it, I get it!", then there is the shift around page 19 or so where it suddenly clicked for me that he was, in fact, telling a story, and not just a series of vignettes, and the work really "unlocked" for me.

RE: the ending, Clowes has always had a wobbly relationship with ending his stories, but I think that's more a function of his characters than anything having to do with plot, per se -- people really don't change all that much, even when confronted with something "life changing". My problem with the end is that I think Clowes felt like he needed to have an "end", and that "epiphany" is the best way to do it, but it seemed very OOC for what we were shown up to that point. That is to say that I tend to think that Clowes himself may be an optimist, and he really doesn't want Wilson to end on a bummer note -- but the characters dictate something else entirely...

CHRIS: Wilson seems self-centered and self-deceiving enough that I don't even buy he had any 11th Hour epiphany -- he'd just hit a point where all the other things he thought might validate him have failed, so he opts for the one avenue no one else can take away from him. Then again, maybe I'm just recoiling away from what is on the face of it, a cliché happy, undeserved redemption. But the entire book (save for the Daddy Daddy scene, which I read as primal pre-Wilson emotion overtaking him) struck me as an exercise in performative self-deception, so I don't know why it'd stop at the last moment. At the same time, the book seems like an effort to empathize with, or at least understand where the Loudmouth/Asshole/Sociopath/Wilson type is coming from. So maybe after all that empathizing, Clowes did want to provide a happy ending. I don't know if this addresses any themes other than trying to determine exactly how unreliable Wilson/Clowes are as narrators, but as a book it struck me as far more of a character study/formal exercise than anything with a Theme per se, though those aren't mutually exclusive and maybe I'm not trying hard enough.

I also still don't feel that Wilson was intended to be in any way sympathetic - he's pretty much utterly contemptible, a (as the back cover says!) sociopath who isn't feeling things, he's emulating feeling them because he feels like it's the right thing to do. He's perfectly self-centered, and any identification I can have with Wilson speaks badly on me as a human being. That's why the book was funny to me - it was easy to feel nothing but schadenfreude for such a complete piece of shit.

JOG: Well, I think your last question there answers the one before it: no, it might not be remarkable if it was prose, but it's not. It's a comic. Like I mentioned above, a lot of the worth of this book for me came from its interplay between mightily shifting observational perspectives and the "Wilsonesque" consistency of the title character. I don't think it's been done in comics to this focused a degree, and I don't think it can be so smoothly executed in prose; you'd need a totally bravura and potentially confusing ever-shifting omniscient narrative approach or a whole bunch of observing characters planted in-story and narrating chorally. Fuck that. This is comics needling its effect right into your brain, icepick style. An arctic shit-knife, if you will.

But yeah, Marc's essay on the early volumes of MOME came to mind as I was writing the Comics Comics thing: "just as not all autobiography is solipsistic, not all solipsism is autobiographical." That's not to say that Clowes is falling into quite the trap Marc declares sprung on most of the debut MOME crew -- a general failure to interface artistically with a world more than a city block or two outside their discreet zones of experience, or even all that curiously as per their experience, if I'm getting it right -- but in the tiny epiphany school, we're not exactly venturing off-campus.

TUCKER: The best Clowes is funny, critical, Clowes. This was funny. It wasn't as funny as the funniest thing he ever did, which is that one or two panel riff on "felix", who spells his name in lowercase letters, but it was pretty damn funny nonetheless.

SEAN: Ugh.

JOG: Heh, is this one of those moments where you identify with Wilson? Please expand!

SEAN: Hahaha! I've just always found Singer's writing on alternative comics self-evidently ughworthy is all. Did it look like I was "ugh"ing you or Abhay or Tucker? Shit, sorry! No ugh intended. However, look for "Ughing Tucker Stone" in theaters this August.

ABHAY: I don't know. Even if Clowes is utilizing something special to comics by shifting visual styles-- well, isn't there a line at which that becomes meaningless? Say you took the movie BRIDE WARS-- Anne Hathaway, Kate Hudson, brides warring, good times-- and you edited it, with those Hollywood computers they have, so that the scene where Anne Hathaway initiates the Bride War looks all SIN CITY, or the scene where Kate Hudson escalates the Bride War is under a blue filter, Candice Bergen is on that crappy Avatar planet, and so forth. That wouldn't be the same movie, no-- it might be more interesting than what they released. But you're still basically watching a movie that's inherently about bride warriors, no? The formatting might add a layer of interest to WILSON, and I can see enjoying it just for having that layer-- but isn't there still something under and independent of that layer that invites a separate reaction? Maybe I've badly misunderstood what you're saying (Jog, that is) though, or aguing a point no one cares about, as nobody seems to be defending WILSON as a "story."

On the subject of solipsism-into-autobiography: mighty clever of Clowes to have Wilson, on the last two pages of the story, consistently facing to the right and having his gray hair thinning out and getting shorter, and then bam, on the last page, there's the artist's self-portrait, which might even be another style of drawing Wilson.

JOG: Plus, setting aside that Wilson is a tightly-controlled work of vignettes, I don't think a movie could ever really have the same effect, in that cinema is for the most part (and definitely in the case of Bride Wars) a photographic medium, running continuously from one temporal point to another, which implicates the viewer's idea of realism at every turn. Like Walter Kerr theorized in The Silent Clowns, pre-talkie dramatic pictures are inevitably distanced affairs to contemporary audiences, because technology has gotten so much more efficient at depicting or analogizing realism (via well-established tenants of film grammar) that silent drama no longer looks 'right.' Silent comedy, in contrast, feeds off of realism being upset to surprising effect, which allows today's audiences to interface with it on a more direct level. The point is, a movie has to contend with the viewer's perception of reality, and somehow flatter or subvert or cope with it; shifting visual perspectives would upset this, a la the blockbuster smash Natural Born Killers, to which I believe Bride Wars was a crypto-sequel.

With a comic, 'reality' can be instantly accepted as whatever the artist can establish; while there's always going to be some readers who'll complain if the art isn't figuratively tight, there's nonetheless a lot more leeway in accepting a comic's drawn, cartooned, scribbled world as bona fied. From there, an artist can shift to guide or provoke reactions, although with Clowes here it's more like veering. But I don't think the same situation is applicable outside of comics. (And anyway, I do think the technique fits in with the story's theme of attempted communication, as detailed above.)

SEAN: Re: crypto-sequels to Natural Born Killers--I believe you're thinking of Zombieland, Joe.

JOG: And then, y'know, Clowes himself weighed in on the topic with his interview in the (now-)current issue of The Believer (Vol. 8 No. 4, May 2010, conducted by my Comics Comics sitemate Nicole Rudick, full disclosure), which is behind a pay wall online, but I bought a hard copy - "I really was exploring the idea of trying to construct a joke out of every scene in a life in a way that would piece together into a narrative." (Pg. 66) There was initially "hundreds of pages" of Wilson jokes in his sketchbook, (Pg. 67), and a terrific influence was Peanuts, and the suggestion from reading a lot of it that an underlying plot might be present. (Pgs. 65-66) If you look at his DCist interview, he adds that no one style made sense when it came time to draw the book proper: "It would have to be this kind of mosaic approach where you're seeing kind of different facets of this guy on different days, and kind of separating each strip into its own different universe that's not necessarily related to the others in sequence." I wonder if there wasn't a strongly facilitative component too - that the book's drawn this way 'cause that's how the book got drawn.

BRIAN: I can't add a lot to the formalism debate you bright minds are having, but to answer the last question of Abhay's, no I don't think it matters all that much -- this is a comics story that could really only be a comics story, and I think it engages you with each page-unit, something that can't be done in film, and would probably be insanely difficult in prose.

ABHAY: Like last year's ASTERIOS POLYP, reactions to WILSON might end up being more focused on the formal choices than the actual content. And I don't think that's a comparison WILSON benefits by-- what I found exciting about POLYP's formal choices was how it added a layer of information to the story, something I don't know that I can say is true for WILSON. Let's back up. With WILSON, Clowes is working in a similar vein as ICE HAVEN: each page is a complete comic, and the art style and/or color palette varies from page to page, including how the main characters are drawn. Which I think raises the question: to what end? Is it contributing information, for you? And that seems to have been answered a number of different ways so far. The great Mr. Paul Gravett began his fine review with the following: "Nothing is left to chance in a Daniel Clowes book." Jog in his Comics Comics review (and sorry if I've misunderstood) suggests that the different art styles reflect how others see Wilson (others sometime being the reader...?). The always-worthwhile Blog Flume blog, on the other hand, suggest a number of possibilities, including that the styles might not mean anything: "As Mr. Ames from Clowes's Ice Haven might argue, 'There is no translatable content contained within each style: it is simply an aesthetic mood, and therefore is beyond the ability of words to characterize it.' Perhaps the styles are not about anything -- rather they create a visual rhythm, a kind of plot that overlaps and diverges from the narrative plot." Where do you come out?

TUCKER: I've been listening to Das Racist a lot, and that's probably ruined me for certain things, and one of those things is that I don't really buy the idea that this "stuff", these choices and varied styles, are being left up to chance. My immediate response to them is that I thought that Clowes was commenting on other comics, on his contemporaries--that he's drawing certain pages similar to Ivan Brunetti on purpose, that his "daddy is dying" side journey is a Chris Ware thing, the little boys in prison page is Peanuts--after I started responding that way, I went looking for it, and now I'm trying to find the Darwyn Cooke's Parker page (blue tones? bedside noir?), and I'm wondering which relationship discussion is supposed to be from Optic Nerve. Whether I'm on any sort of right track or not doesn't particularly interest me, as this obsession has effectively determined how I'm interpreting Wilson for the time being, but right or not, I'm firmly in the camp that Gravett is right, and none of the choices are left up to chance.

JOG: I think I've pretty much said my peace already on this, although I guess I should add that the multiplicity of perspectives on Wilson doesn't represent in-story observing characters, but the reader as forced into the position of different, biased, tilt-headed straining faux-observers, like you're becoming a new 'reader' on every page. I totally agree that there's multiple interpretations, sure; I think the book benefits even less from Ken Parille's intuitive-shades-of-mood-beyond-description/pure-visual-rhythm option(s) than pairing it up with Mazzucchelli, since that I think that interpretation brings to mind no particular substantive interaction with the writing save for putting the scene breaks after punchlines or those goofy dramatic beats. That's just one possibility suggested in that post, I know, and anyway I'm not too far from intuitive shades of mood myself, since I'm not convinced that each 'style' as a consistent, coded meaning. But I don't think intuition's all there is.

SEAN: I say this in my review, but I think the gag is that amid all the varied styles, amid all the mastery of the craft of drawing and coloring that Clowes brings to bear here, Wilson's still the same.

DOUGLAS: The "different style on every page" thing seems like a display of mastery on Clowes' part rather than particularly like an additional layer of meaning added to specific scenes. It's also worth noting that all the stylistic choices Clowes makes here are within a distinct, limited range of visual style.

SEAN: Yes. Every single one is recognizably Clowes--in fact, I'm reasonably sure he's used every single one before, perhaps in Ice Haven alone. This isn't some chameleonic tour-de-force of mimickry or experimentation. That's not a complaint, mind you, just an observation.

BRIAN: What Douglas said.

DAVID: I largely agree with these - I don't think the styles were part of any grand pattern, or that they're express homages or map out some sort of thematic unity between the similarly-drawn strips. I think it's just Clowes using the style he thinks is funnier or more effective for that particular gag or emotional punch.

JOG: Tucker, I'd be interested in hearing you expand on your idea up above. Like, over at my Comics Comics thing where I wondered if Clowes was "fucking with us," part of that was wondering if he wasn't mixing in aspects of stereotypical sad, tortured, obsessive lit comics characters as a means of making Wilson-the-character even more abrasive to acclimated readers, not so much as critique but as a rotten Easter egg to stink up the reading for jaded nerds - Clowes knows his comics, so I don't think it'd be out of his reach to play that kind of game as a character thing, knowing that it might not register to casual bookstore browsers. But are you saying it's a broader, comics-on-comics criticism at work? What's your theory on how that plays out across the book?

CHRIS: Even before he started doing formal exercises in "shifting style" like Ice Haven and Wilson, I feel like Clowes has been far more of a chameleon than nearly any of his contemporaries: guys like Ware and Tomine may have played with a variety of styles back in the day, but both have gradually whittled down their work to a singular style. Charles Burns, Peter Bagge, Los Bros, pretty much anyone who falls alongside Clowes in the pool of Men of a Certain Age Who Do Comics Michael Chabon Might Have Been Bitching About In The Above-Mentioned Quotation -- they've all chosen to work almost exclusively in a singular trademark style. Clowes has played around with styles enough over the years that he can pull something like Wilson off and still have every page look like a "Clowes Style" as opposed to a pastiche to a foreign style, and you could try to map the pages to "Yellow Streak, Ghost World, David Boring, Pussey, 20th Century Eightball Intro" paths too. I'm willing to believe there's an element of "fucking with us" involved with some of the choices, but I don't think that was a primary goal. I don't think there was any primary agenda to the shifting styles, though I also agree nothing was "left to chance". Going back to the previous question (which I didn't have anything insightful to add to) I do wonder if the direct showiness of this specific creative decision is giving it more attention than other deliberate choice that any creator makes.

ABHAY: Oh, to be clear, Chabon wasn't complaining about comics or comics creators, but about serious prose short fiction. Okay. Let me get bold-faced because it's time for the next question. Setting aside the "what does it all mean" question-- did you LIKE the format choice Clowes made? Did you think it made the WILSON experience better than it would have been had Clowes maintained a single style throughout? Do you think "serious scenes look serious, funny scenes look funny" robbed you as a reader of your own authorship, of being able to create your own interpretation / conclusion of events presented? (To the extent that description is even true-- Page 62's Last Time and Page 49's Polly's House might suggest otherwise). By insisting to us how we should see Wilson at any given moment, is Clowes in essence doing the same thing Wilson himself is supposedly guilty of, bleating on and ignoring our own possible contributions to the conversation?

SEAN: I don't think that's what's going on, so I have no problem with this. By all means let a thousand flowers of Dan Clowes drawing style bloom.

JOG: No, I don't believe it's coded that way. A bunch of the really blatantly 'funny' bits are closer to the realism end of the scale, like where he asks the prostitute for a blowjob, or confesses his role in sending the box of shit. In contrast, the big breakthrough final page is among the more cartoony. And while the visuals force us into a bunch of different perspectives, I think there's still a lot of leeway for a reader to determine how the style interacts with the text. Like, is the monochrome look wistful or funny or depressive? That's up to the reader - what matters is that they're faced with differing situations on almost every successive page.

TUCKER: Boggie, shit. That's weird. I'm in your house, Abhay. I'm eating your almonds, I'm kissing your quilts.

JOG: Probably the first prison page (54, "Hard Time"), which I thought was the funniest part by far - that's the one where Wilson launches into a typical, I'd say deliberately-lame-on-Clowes'-part rant, and in the last panel his scary cellmate threatens to rape him. And yeah, I know: oooooh, Mr. Middle Class Hetero laughed at the gay prison rape joke! But, it's great in so many ways: (A) how the very setting is an extra punchline for the off-panel confrontation on the previous page; (B) how it's a long-game punchline to the parade of saps across the entire first half of the book sitting quietly while Wilson goes on and on and on, because here's a dude who's completely not going to sit in a cell with that and he's gonna communicate his position in an admirably succinct manner; and (C) how the dangerous cellmate speaks in this horrible, cartoonish regional dialect, while Clowes draws him in the stiffest, most serious manner imaginable. It's a lot funnier now that I've explained my feelings. Also, "so many" meant three.

SEAN: I like the Dark Knight page for its ability to provoke precisely the reaction Abhay has below. Getting pissed off about superheroes was maybe boring like a decade ago when that was still the prevailing sentiment among alternative-comics readers and creators, and, like, the Comics Journal message board was the only game in town. But in this the Every Knee Shall Bow Era of nerd-culture dominance, SOMEONE'S gotta kick people who worship the movie with the second-best movie Joker in the balls. At any rate he's making a point specific to superheroes that doesn't have anything to do with film or screenwriting in general. I also liked the page about fucking hating all religion, because word up.

DOUGLAS: My favorite is pg. 51, "Pure Bliss"--that's the one that cracked me up on my first re-read, because the punch line there is the first time Clowes lets on that he hasn't quite been telling us everything about what's been happening in the sequence leading up to it.

BRIAN: My two favorite pages are probably "FL. 1282" and especially "Agent of Change", because those seem like universal annoyances to me.

DAVID: "Taxi Cab," without a question. It cracks me up every time I look at it - the awkwardness of the entire exchange, the goggle/cross-eyed look on Wilson's face in that fourth panel juxtaposed with that dialogue snippet ("I want the actual kind you can fuck. For money.") -- trying to explain it ruins it, but I find almost every panel of it amusing, and overall it's one of the funniest single-page gag strips I've seen. I love it.

CHRIS: Nearly all the previously shouted-out pages are worthy choices, but to avoid repetition I'm going with "Frankenstein" -- I don't think it's actually supposed to be the same guy as "Table Sharing", but the pair of pages are a cute and concise reminder of just how utterly inessential Wilson's conversational partners are to him, and how memorably unpleasant a lowgrade jerk like Wilson can be. I suppose it's a gentler companion to "Hard Time", but I gently fist-pumped for Frankenstein's gentle rebuff.

ABHAY: Least favorite page? I think mine was Page 32's The Dark Knight, the one where a cab driver tries to engage Wilson in a conversation about a Batman movie, and Wilson began to rant about superheroes-- all of which struck me as disagreeable for two reasons. One, it seemed like a relic from some earlier age of art-comic, where being adversarial with mainstream comics was often (and arguably, incorrectly) seen as necessary. It again conformed to Mr. Singer's complaints, namely his complaint that "Clowes's work also seems to be susceptible to a problem that has undermined many an alternative comic. He can't escape the superhero comics he so disdains because he never stops telling us how much he disdains them; nor are his criticisms particularly novel." But also: two, it reminded me of Clowes's own failures as a filmmaker. I didn't care much for THE DARK KNIGHT, but ART SCHOOL CONFIDENTIAL is as much a piece of shit as any I've ever seen. And that, in turn, reminded me that... Clowes is a Hollywood screenwriter (with wife and child and beagle according to his bio) seeking to profit here from a story about a possibly mentally ill character. At what point, is there something cruel about that? Or just dishonest? If the vision of life Clowes is advancing is life as tragic-- he's traveled the world, thanks to a life spent drawing pictures of chubby near-sighted girls! Isn't his own biography proof that life is actually more bizarre and weird and hilarious than any "life is tragic" summation can capture? Rationally, I know what I'm saying is probably too hyperbolic, and that Clowes' extremely limited fame & minor success doesn't mean he somehow surrendered the right to talk about how he perceives life is for other people. But I know my own weird class resentment is an issue I have with this "genre" of comics, nevertheless.

JOG: Huh, brings to mind Gravett's point that "Wilson" is a partial anagram of Clowes' name. My initial impression was that you're misinterpreting the scene, since Wilson's a total goon and his speech is therefore meant to be annoying, but then I noticed a little 'out' in the punchline, which doesn't suggest that Wilson is so much wrong as equally guilty in buying in to the evidently idiotic chest-thumping babyman horseshit of superheroes. Or maybe Wilson just realizes his breach of conduct, given that he needs to get a ride from this guy, and immediately compromises himself in asking about Iron Man. Same result. Anyway, it doesn't really bother me, particularly in that The Death Ray exhibited a pretty keen-eyed take on the superhero genre, wherein Clowes lays out his particular interests - it's not a sneering blanket dismissal of the genre, it's a sneering informed dismissal of unfavorable generic aspects. And while I've never seen Art School Confidential, I don't think Clowes' own screenwriting acumen or lack thereof affects Wilson's commentary, which is focused on broad social-philosophical matters that implicitly acknowledge that a film can be 'good' in a technical/whiz-bang entertainment sense while still being repulsive. Like, it's not a good commentary, or one I particularly agree with, but I don't feel the same annoyance you do.

SEAN: Haha, I thought he brought up Iron Man just to be a dick!

TUCKER: I took it that his question about Iron Man was actually sincere, that for all of his gooniness, he genuinely wants to know what happened in these things that he's sure are stupid, for stupid people, etc. Sort of a parallel to the way you describe the character above, he's above poppy entertainment but still wants to engage with it. Then again, it would help my case if he'd actually seen Dark Knight in the first place.

ABHAY: Huh. I read it as Sean did, that Wilson was being patronizing. I'm not sure how often we were supposed to be laughing AT Wilson and how often we were supposed to be WITH Wilson laughing at the "absurdity" of his world and its numerous nail salons, etc. I have a harder time with the latter kind of comedy than the former, in general, maybe-- which has always been an issue with Clowes for me since his more comedic pieces have been on that line somewhat often. Late in the book, there's a scene where Wilson complains how much the future sucks, because he doesn't get to read Ellery Queen mysteries anymore, and I wasn't sure if we were supposed to feel sympathetic to the opinions he was expressing or pity the pathetic old man (neither of which I was really willing to do in that case).

BRIAN: "Dark Knight" made me think of, for some reason, "Feldman"

JOG: I also don't agree the Clowes' vision boils down to tragedy; surely he relents in the end that even a dolt like Wilson is capable of momentary peace, which would then allude to his own contented life, if indeed we're hitting on Wilson-as-solipsism.

ABHAY: He seems to surrender his ego for a brief moment, sure, but only "immediately" prior to the total spiritual annihilation of those white pages. Maybe it's unhealthy to view death as a "tragedy", instead of a beautiful process of nature, like pollination, but ... guilty! "This will all end with total spiritual annihilation"-- best Valentine's Day card ever.

JOG: Ah! You see, I didn't take the white pages as signifying Wilson's death - it was more like a television cutting broadcast to white noise, like: story's over! You can't see any more than that! Our POV ventures away from Wilson as he sits and enjoys his revelation on the last page: we have to leave now. I guess he could die, my uncle sure did, but -- and I realize I'm getting really really really subjective now -- I don't see it as cruel so much as relenting to give the character something nice to have planted in his mind for his last image.

ABHAY: Well, at the risk of belaboring the obvious, I just thought if what we saw in the preceding pages was not Wilson's "body" but his essence, then the total absence of that essence on the white pages was the total vaporization of his soul basically-- the heaven-less afterlife Wilson had been predicting throughout the book, quite accurately. I can see how "fictional characters all have their souls obliterated when you cease observing them; Merry Christmas" might sound a bit severe, though.

JOG: As for my personal least favorite - um, I guess the one on the phone with his dad I mentioned before (19, "Bad News"), since that's the first and worst of the gag-swapped-out-with-a-honking-dramatic-beat pages.

DOUGLAS: Maybe pg. 17, "Fat Chicks," which is the most egregious example here of Clowes doing Brunetti doing Clowes, isn't particularly funny on its own, and doesn't add anything to our understanding of Wilson--it's just repeating the same gag we've already seen a bunch of times.

BRIAN: "Hard Time" didn't work for me, but that's more from the "look a lot of time passed, and even more stuff happened off camera" aspect of than anything else.

DOUGLAS: See, I liked that one for the reason you didn't!

CHRIS: Wilson and Pippi end up going to see some sort of movie with big explosions and falling buildings in "11 O'Clock Show", so there's definitely a level of hypocrisy to his dismissal of Dark Knight, unless the page was supposed to be a super-meta-critique of comics enthusiasts who think that Superheroes Are For Children but get really excited for cartoonish male power fantasy books if they involve, like vampires or super spies or futuristic journalists or chainsmoking cyborg barbarians or something, like spandex is a mystical talisman that separates the Childish from the Mature. I'm almost certain this was not Clowes's intention.

ABHAY: Do you think WILSON is a step forward or step backwards for Clowes? I've seen some reactions online that have suggested many see it as the latter. How do you figure it in the context of his overall career? Is this a thing you think about? If Jog will allow me to quote him again "I think the wider critical/(sub-)cultural conversation has packed lit comics stereotypes into a firm enough state by 2010 to wonder freely if Daniel Clowes isn’t on some level fucking with us[.]" On the other end of the spectrum, you have this quote from the goodly Mr. Timothy Hodler from the comment section: "Clowes is definitely getting more and more Nabokovian (more the authorial puppetmaster, the magician who lets the audience pierce the veil, but only rarely and briefly) as time goes on, and some find breathing that particular kind of rarefied air stifling. (Not me! I love it!)" What do you think? Where do you come out on a Jog-Hodler continuum? Physically aroused? Me, too.

JOG: That's it, Abhay - you'll be hearing from my lawyer. Fair use? More like fair I'm suing you.

SEAN: It's not on the level of his back-to-back masterpieces in Eightball #22 and #23, but that's fine. It is what it is. People can step sideways or diagonally or whatever.

DOUGLAS: Yeah, I'm with Sean. I'm not as crazy about Clowes the formalist who makes his characters and plots secondary to Cartooning with a capital C as I am about Clowes the satirist or Clowes the observational character-builder; WILSON is pretty much a misfire for me (so were "David Boring" and to a lesser extent "Ice Haven," but I agree that #23 was a masterpiece, if that helps you calibrate where I stand on him). But the last piece I read of his was that super-compressed story in Kramers Ergot #7, which I really enjoyed; forcing himself to do something new gave it a lot of energy, I thought.

SEAN: Wow, Douglas, you may be the first anti-David Boring/Ice Haven Clowes reader I've ever heard of!

CHRIS: I wonder if Wilson is suffering from how it's generally being framed as "the first graphic novel from Daniel Clowes after how-ever-many-years since the last issue of Eightball" as opposed to "something that Dan Clowes did". I'm reminded of Evan Dorkin's tear-down of Seth pre-apologizing for Wimbledon Green as a "minor" and "sketchbook quality". If anyone walks into Wilson thinking it is going to be Clowes's Asterios Polyp or Jimmy Corrigan they're going to be disappointed. I don't have a flowchart of Dan Clowes's evolution as an artist -- what Pokemon will he turn into?? -- but as "something that Dan Clowes did" I enjoyed it. It's not his best, but nor does it make me fear he's going to slide into dotage.

TUCKER: There's no location to put this, but Chris is reminding me of it, so I'll put it out there: that whole "first original graphic novel from Daniel Clowes" thing is obnoxious, and I'm starting to wonder whether any of the creators who are getting this badge thrown on them are actually willfully reaching for it. See: Asterios Polyp, first graphic novel. See: Crumb's Genesis, first graphic novel. I could wrap my brain around it more if it made sense to Joe's "casual audience", but it really doesn't when they're casually picking Wilson off the shelf, where it sits right next to things like Ghost World & Velvet Glove, or at least it doesn't whenever those things are in print, which seems to be "occasionally". It's not a label for any of us, as far as I can tell, it's not for the casual browser, it seems wholly created for author blurbs, press releases & pissing off Eddie Campbell. On the continuum question, your real one, the one I can't really be accused of hijacking since I'm adding this at the absolute last minute: it's different enough from his previous works that I can't help but call it a step forward, because I sincerely believe that's the only thing that matters when it comes to comics, etc, anything. A step backwards for me would've been D. Boring Pt. 2, Return to Ice Haven, so on. This wasn't totally my bag of hammers, but I think I'm probably happy enough with it that you'll find me lurking on the Tim Hodler end of the pool. I'm a power bottom.

TUCKER: I think it's a good thing, generally, for cartoonists of any stripe to be able to deliver work in whatever format they most prefer. Not having the benefit of facts to draw from, I can only assume that Clowes released Wilson the way he wanted to release it--as a stand-alone, non-serialized work--because I'm of the opinion that Clowes is in a position where he can choose his method freely, due to his previous successes. If that's not true--if he wanted to serialize Wilson, and was convinced otherwise due to financial reasons or publisher prodding--than I'd feel negatively towards the method. As far as I'm concerned, and this is where I might disagree with Brian, I think the artist is the one who should make that decision, and the feelings of a publisher, retailer or reader shouldn't be given much consideration, if any at all. That doesn't mean I think their opinions on the final product are meaningless, but I don't think that sort of stuff should come into play on the creative end of the table when the work is actually being generated. Having comics in multiple formats--annual books, monthlies, web weeklies, archival bricks--doesn't strike me as something that has a lot of negative aspects. I don't believe for a second that limiting creators to the current whims of the audience is in the best interest of creating any type of art. The contradiction to all this pro-art talk is that, as always, it certainly helps to have the things I like be profitable enough that the people involved can make more things that I like, and from that perspective, Brian's general concept--that selling an Eightball version of Wilson 1-10 means Clowes and everybody else might end up with more money when it comes time to release the Wilson hardcover--might have some truth to it. I don't think that's the case with this specific work--the kinda dopey ending aside, Wilson doesn't really lend itself to satisfactory serialization. (Am I wrong on this? Eightball issues would've been purchased and read by me, certainly, but i'm a fucking lifer whose opinion on these things often runs contradictory to normal human beings. Would people have wanted to read one-page Wilson strips every weekday for the two odd years it would've taken for the story to finish? Would any of you wanted to read this over the course of a few years in 20-30 page chunks so that Abhay could fill up his precious longbox?) I'm enough of a selfish prick that I would be totally happy if Chris Ware's current ongoing stories came out in more frequent chunks, but that's because his chunks always read like they're designed to be read that way, that the final brick style collection of Jimmy Corrigan is a pain in the ass to read in a way that the individual Acme chapters aren't.

BRIAN: I don't think that Wilson would have worked as "Three issues of Eightball", or whatever, but I could see it working extremely well as interstitial material between other stories in a periodical -- say, over 10-12 "issues". Particularly because of the narrative shift around page 19 that I noted before. I like work that reads one way in serialization, but then takes a totally different tone when bound together. I think that, too, is something that is really unique and special to comics.

SEAN: Chris Ware decamped from Fanta to D&Q too, don't forget. Brain drain! I, I remember Ware and Clowes standing by the wall; the guards shot above their heads and they kissed as though nothing could fall. Anyway, I've actually never read Clowes in serialized fashion. The only Eightballs I've read contained the stand-alone stories Ice Haven and The Death-Ray, I read all his older material in collected form, and I read Mister Wonderful in one sitting over two years after it wrapped up. So this isn't that big a change for me. In general, I tend to think that it's younger artists who'd most benefit from an economic model that still permitted serialization, since in theory at least it would afford them more of an opportunity to experiment, work at a rapid pace, get feedback, and so on. An artist in Clowes's position doesn't seem to have much to gain from it.

JOG: I should note that Clowes himself addressed the publisher issue in the Washington City Paper interview Douglas linked to above - basically he finished the book without a publication deal and decided it should go with D&Q, to which he'd promised a book years ago.

BRIAN: This is me with my retailer hat on now, but I can say that when Eightball was a 3-ish-times-a-year periodical, in the first month we'd sell roughly 200% of it than we would whatever the best-selling ongoing hero book was (Uncanny X-Men then, probably Avengers now), then we'd selling that same number again over the course of the next year. Based on current velocity I'm guessing I'll sell something like 75% of Wilson-as-book compared to Avengers (ugh, what a comparison!) in the first month, then maybe 125% of that in the next twelve months. So the question somewhat becomes "how much does the numerical size of the audience matter to a creator?" I'm of the opinion that the "book market" is going to sell whatever they're going to sell of a work whether or not it was serialized in the first place (from an established creator like Clowes)

For this book, in particular, I think that the $21.95 price tag is just over the $19.95-psychological-barrier that people have for GNs, and that a second revenue stream in the form of serialization could have potentially gotten that price down below that magic number, which would probably end up shifting more units over the course of time, as well.

Of course, I tend to suspect that a number of the members of this round table got review copies of this book, so you're maybe not thinking about the arcane business of pricing whatsoever! (Which, of course, is how it should be; just saying)

The other factor, of course, is that Clowes' last solo work, Ice Haven, was released in June of 2005, which means Clowes has been "off the market" for some five years. Clowes is established enough that this is probably not a dire thing for his career, but for new or emerging creators it is really hard (not impossible) to build an audience if that much time passes between releases.

ABHAY: I don't know if this adds anything, but here is a quote from a recent Clowes interview with Time Out New York that might be of interest here: "I felt like the whole comic book thing is over. Like we can’t go back to that anymore. Now that you have to charge six dollars or whatever for a comic book it’s not the same thing as it was. It just seems like an affectation at this point in time. [...] That whole world we were in, it seems so, so lost. The whole world of zine culture and doing your own little comic pamphlets and that stuff. It’s very hard to explain to someone who was born in 1990 what that’s all about."

DOUGLAS: Wow. That's a little disturbing--maybe the problem for Clowes is that the class of 1990 is no longer making zines and little comic pamphlets (or, to be fair, that there's not really a single publisher right now in the particular position Fantagraphics occupied in 1990 with regard to serialized art comics), but I came home from both MoCCA and Stumptown in the last few weeks with enormous piles of homemade comics by people born around 1990 or a little earlier. I don't think WILSON would have been particularly effective serialized a page at a time (I'm imagining it as a web-comic, and I bet I would've thought "get to the point" very quickly); I can't see it working a chunk at a time any more than Asterios Polyp would have. But D&Q is certainly not unwilling to publish eighty-page hardcovers as "issues of ongoing series" (looks like both Acme Novelty Library #20 and Palookaville #20 will take that form this fall. Thought experiment #2: would we be thinking about this differently if its cover said Eightball #24? It'd sure be harder to sell to a bookstore audience, I'd bet.

TUCKER: Yeah, that line from Clowes isn't too far removed from other cartoonists "of his generation" in assuming that zine and mini culture is dead simply because Fanta & DQ barely participate in it beyond a couple of annual floppies. Plenty of new stuff on that front, it's just not something he's bumping into.

SEAN: The folks with more history on this list can correct me if I'm wrong, though, but as best I can tell mini/zine culture now, at least in its most potent and fecund form, treats minis like art objects, not like the "bang 'em out at Kinkos" direct line to the cartoonist that they used to be...and Clowes's use of "zine culture and doing your own little comic pamphlets" aside, the full-fledged alternative comic book from an independent publisher is pretty much dead but for quixotic projects like Alvin Buenaventura's thumbed-nose-at-Diamond line, right? That strikes me as fairly uncontroversial.

BRIAN: This may be one of those "chicken-and-egg" things, but "alt comics" "don't sell" because no one is producing them in critical-mass-enough numbers any longer. The shift, particularly with the "fathers" like Clowes and Bagge and Tomine and Crumb and Los Bros to "annual or less" output means people are no longer walking into stores looking for that kind of material, on a regular basis, any longer. And that drastically reduces the chances that the next, emerging artist can succeed "on the coat tails" (as it were) with periodical releases. What we need is 20-30 cartoonists each committing to 2-3 releases a year, so that "every week you walk in there might be something that tickles your fancy".

The beauty of the periodical is that it encourages sampling, in a way that GN-formats very pointedly don't. The alt-comics reader (to the extent you can pigeon-hole readers, which is, actually, very low) isn't coming into the store weekly any longer, or even monthly. They're making 2-3 trips a year, at best, which further reduces the hard number of readers supporting that work at retail...

But, to get back to the initial question: is there "some key quality of WILSON would have been destroyed had it been serialized?", no, I wouldn't say that at all.

SEAN: It occurs to me now that Wilson could have been doled out a page at a time online as a webcomic in a way that would have worked rather well for the material.

SEAN: Where are you getting a mercenary vibe from this project, Douglas? I'm really not seeing that in the book. I also don't see why poo-pooing the webcomics financial model means he's not enjoying himself doing what he's doing now. If anything, couldn't you infer the opposite? If the argument is just that, well, he sounds dour in an interview--this IS Dan Clowes we're talking about.

DOUGLAS: Oh, I don't think it's mercenary, I just think it's dourer than a lot of his work has seemed to be in the past.

SEAN: Ha, I think my "this IS Dan Clowes we're talking about" still stands.

CHRIS: When Clowes was talking with David Hadju at Strand last week, there was a prepared slideshow of images, and one was a group shot taken at some comic shop in the mid-1980s. Through the haze of three decades I couldn't really hash out the "point" he was making when he said words to the effect of "this was all we had for comics culture back then" -- those mustaches and haircuts and ring tees wouldn't have looked out of place at MoCCA at all -- but I do understand what he was talking about when he described how early issues of Eightball (and Cerebus and Love & Rockets etc.) were shoved in the back of the store in an "Adults Only" box. The whole 'zine/indy comix culture was very much based on on that connection to a far-flung audience that felt a secret bond, like Douglas described. Nowadays, through a combination of the Internet existing and a legitimization of comics and many other 'zine-y topics, the impulse to bang it out at Kinko's isn't really there, unless you're doing it for some sort of artistic reason. Clowes's generation have all gentrified into having book deals and the ability to put out nice looking Books, so it's understandable that very few people (John Porcellino? Anyone else?) go to all that hassle. If you don't have any attachment to the trappings of the 'zine culture, you're much more likely to focus your energies on blogs and webcomics and the like. Do any of us write for APAs? I'm just (barely) old enough to have an affection for the 'zine era, even though it was more my hypothetical-older-sibling's bag that I peeked into before I was really old enough. Still, that sort of thing catches my eye at MoCCA or anywhere else I happen to see it, but these days they often come with silk-screen covers and prices at $5 or more, something that makes me recoil even more than an over-twenty-dollar slight graphic novel does.

Rationally, I agree with Tucker's assessment that it should be the prerogative of the creator. I see Brian's point coming from the publisher/retailer perspective, but personally I am grateful for the proliferation of original graphic novels, as it helps me conserve the space and money that otherwise gets doubly eaten up by my compulsive re-purchasing of things once they're put out in collected editions. This runs directly counter to what Brian and D&Q probably want to hear -- they could've had my money twice! -- but I'm selfish.

ABHAY: Final thoughts? Ratings, if you prefer? Lessons learned? I learned how art can bring an array of very different people together to discuss, to debate, and even to celebrate -- of course, I'm referring here again to the movie BRIDE WARS. I learned that internet people can even disagree violently about the meaning of one-page gag comics, that really we're all just one ZIGGY away from an all-out knife-fight. I learned, based upon the responses to the first question, that apparently, I'm the only one who has enough self-esteem issues and personality defects to relate to schlubby Dan Clowes characters... and that made me feel pretty great about myself. And sometimes, I didn't learn anything, but was instead embroiled in an erotic game of cat & mouse. But who was predator, and who was prey? That is one sexy question that may have to go unanswered.

BRIAN: Savage Critic-style, I thought in the end, that the book was VERY GOOD. I'll opt not to discuss your sexiness.

SEAN: I learned that I would very much like to do this sort of thing with y'all again...

BRIAN: I think we should do this at least once a month, each time with a different person moderating and coming up with questions, maybe? Or maybe that's insane...

DOUGLAS: Hey, Brian, is INTERESTING TO WRESTLE WITH one of the official SavCrit ratings? I always forget.

JOG: True. I'm hesitant to say 'it sparked discussion,' because that's a crummy, overused defense -- I can stand up at Sunday Mass and fart in the collections basket, and that'll spark discussion too -- and I also think there's a hazard in crediting a 'literary' comic with formal investigation on its face, since I think that inquiry is arguably a base component of comics aspiring to a literary quality, if not necessarily to as deliberate a degree as found here. But - there's a worth in how this book's visual mechanics compliment its themes, even if it only presides over what I thought were pretty facile anxious man insights and not-that-funny jokes. Still liked that prison page, though.

SEAN: I laughed hard at this thing, man!

DAVID: Yeah, I stand on the VERY GOOD side of this fence myself. I enjoyed it and had a lot of fun reading it, and it's a great Art Object to have around - I can pretty much open it up at any time and enjoy any given string of pages, and sometimes find some narrative hooks between the pages that I hadn't noticed before. It's also wonderfully made by D&Q, and it's nice to buy a $23 hardcover that isn't bound with glue and hollow cardboard.

TUCKER: I'm comfortable with GOOD on this one.

CHRIS: We're in this Low Self-Esteem battle together, brother -- I was self-conscious enough to make a point of wearing my contacts the day I went to see Clowes for fear someone would think I was cosplaying as [slightly] Younger Wilson. I was surprised at how little I found myself thinking about Wilson after I finished it, and how little I had to say about it to my circle of Comic Friends. I still think it was GOOD, but at a certain point I wonder if that reaction isn't just because I like getting more Daniel Clowes comics.