Kramers Ergot 7

/ A lot of comics were the subject of controversy in 2008: Ice Haven, Memin Pinguin (remember that?), that one comic where the dog ate the teenagers. Surprisingly, alt comix anthology Kramers Ergot 7 was arguably the most controversial comic of them all. The issue was not the content (though much of it would scandalize those who were offended by Ice Haven), but the price of the book. Some of the controversy came from those who supported (or who were at least familiar with) the anthology series and its contributors, but who regretted the high ($125) price point. Others came from people who had apparently never heard of the series, or who had little interest in the sorts of comics which had been featured in previous volumes of Kramers Ergot.

A lot of comics were the subject of controversy in 2008: Ice Haven, Memin Pinguin (remember that?), that one comic where the dog ate the teenagers. Surprisingly, alt comix anthology Kramers Ergot 7 was arguably the most controversial comic of them all. The issue was not the content (though much of it would scandalize those who were offended by Ice Haven), but the price of the book. Some of the controversy came from those who supported (or who were at least familiar with) the anthology series and its contributors, but who regretted the high ($125) price point. Others came from people who had apparently never heard of the series, or who had little interest in the sorts of comics which had been featured in previous volumes of Kramers Ergot.

By the time Kramers Ergot 7 actually came out, however, the furor had mostly subsided. It's almost too bad that the controversy didn't happen closer to the book's release, because the actual content of KE7 hasn't actually received nearly as much attention as its price point. And since the only thing which could justify the high price is good content, it seems like a relevant issue. Kramers Ergot 7 was the most anticipated comic of the year for many people, including myself. How did reality stack up to expectation? The answer, along with my best attempt at providing some art samples (this thing's way too big for my scanner, and our digital camera/the person operating it aren't ideal), comes after the break.

Usually anthologies are all over the place in terms of quality and content, but that's surprisingly untrue for Kramers Ergot 7. This volume boasts an incredible roster of cartoonists, including several best-of-their-generation types, folks who your more literate friends and acquaintances might have actually heard of. Thousands of New York Times readers are familiar with Seth, Chris Ware, Jaime Hernandez, and Dan Clowes from their contributions to the Sunday "Funny Pages" section. And while Adrian Tomine hasn't had anything appear in the NYT (yet), he fits in with this group pretty well (surely you remember this picture from, you guessed it, the New York Times). These cartoonists' contributions to KE7 are, for the most part, the sort of thing that would appeal to the audiences they've built over the last decade or so. Ware's story is actually a continuation of his NYT work, while Seth has another contemplation of the Canada of yesterday (though it's not nearly as bittersweet--or as good--as George Sprott). Tomine's story fits pretty neatly within the niche he's carved out as well.

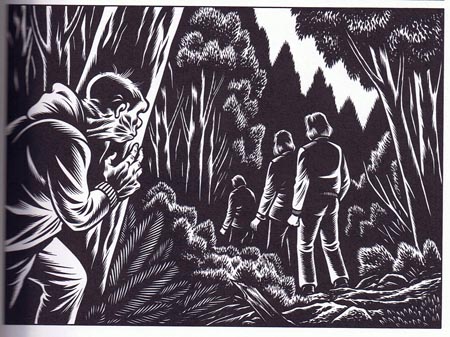

I found Hernandez' and Clowes' contributions the more interesting from this group. Hernandez' story is one of the denser single-pagers in the book (and there are a lot of dense single-page stories in KE7), a frantic, entertaining study of memory and sentimentality. Clowes' story, "Sawdust," is excellent, effectively a counterpoint to his equally good NYT story, Mister Wonderful. There's a real similarity between the protagonists--age, stream-of-conscious narration, desire for romance--but this is a much darker, even noirish work. I don't think Clowes has written many lines funnier than "Lucky for me, he couldn't dig a grave for shit!"

Daniel Clowes

But the most famous cartoonist featured in KE7 is unquestionably Matt Groening. I was as surprised as anyone to see him announced as a contributor, but his single page strip is one of the best in the book. Groening produces an homage to this illustration, but with a focus on Southern Californian despair which should be eminently familiar to anyone who's read Life in Hell over the past few decades. "River of Unsold Screenplays" replaces "Failure," "Grad School/No Escape" replaces "Charlatanism," and so forth. It's no bleaker than "Love is Hell" or "School is Hell," but the context is so much different now than in the 1980s. These days, Groening effectively represents the best case scenario for the modern alternative cartoonist. If anyone knows anything about the "Road to Success," it's Matt Groening, so it's rather dispiriting to see a long slide labeled "Disappointing sales of second album, novel, play or film." And you have to kind of wince at a series of spider webs spun by "Psycho Exes," or a cliff labeled "ungrateful children." (Simpsons fans might make note of a balloon labeled "Crackpot cult religion, you know the one.") It's a great encapsulation of Groening's Life In Hell, and one of the best cartoons of his career.

And that about does it for the very famous people, though there are plenty of other contributors who are well-known within comics circles. Ivan Brunetti plays with the book's mammoth size by forcing the reader to turn it upside down to finish his story--the joke's on us, since this thing weighs about as much as a St. Bernard. Kevin Huizenga does something similar with his page. Kim Deitch basically distills his story from Pictorama into three pages, but it's worth the repetition to see all his incredible bottle cap designs--or are they replicas? I have to admit some ignorance of the bottlecap collecting hobby here, but they're really nice, charming drawings either way. Ben Katchor contributors two stories about architecture in his imagined New York; if that sounds good, you won't be disappointed when you read them. Richard Sala's single page is mostly a showcase for his gorgeous art and character design (we're talking monsters and villains in vibrant watercolor here).

Richard Sala

The lesser-known contributors bring just as much--probably more--to the table, plus they provide the book with some degree of aesthetic and thematic coherence. When you flip through Kramers Ergot 7 for the first time, you're not struck by the star-studded lineup so much as the barrage of colors from story to story. Given the dimensions of the book, it's practically an assault on the eyes. Many of the contributors work in limited palettes, making KE7 a staggering visual experience. Stories by Sala, Dan Zettwotch, Frank Santoro, Blex Bolex, Anna Sommer, and Helge Reumann are especially noteworthy; the blue and red motif is particularly popular (and effective). Deitch's soothing pastels and Ben Jones and PShaw's multi-tiered, multi-hued contributions also stand out.

Blex Bolex

Once you actually start reading Kramers Ergot 7, you might also notice how many of the contributors have produced work dealing with the fantastic. Perhaps inspired by the towering dimensions of the book, a good many of these cartoonists turn to religion and mythology in particular. Several reviews have cited Tom Gauld's four page retelling of Noah's Ark as a highlight of KE7, and justifiably so. I've long admired Gauld's work, and it's never looked better than it does here. Gauld takes advantage of the book's size as well as anyone, using large panels to underscore the surprise of Noah's sons in finding their father wasn't just a senile old weirdo. The dense linework is stunning, reminiscent of Edward Gorey in the larger panels.

Tom Gauld

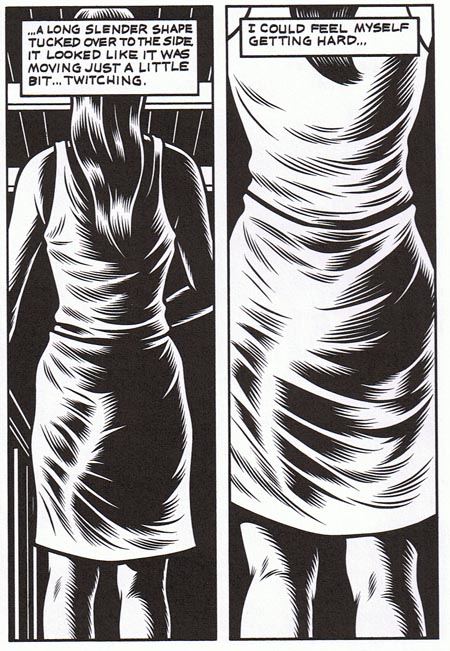

Other contributors' stories explore religion in a more general sense. The first of Conrad Botes' two stories is sort of like a pantheistic Book of Job, only without any reward at the end for the protagonist. There are a lot of horrific images inKE7, but Botes' depiction of a series of divine punishments is particularly unnerving. John Brodowski's single page story is one of the best examples of dark humor in the book, dealing with the ill-fated resurrection of an arctic traveler. Joe Daly's cold, precise drawings depict a disturbing creation myth, with bizarre creatures with enormous phalli emerging from the ocean and raping the land-dwellers, who immediately gives birth to a swarm of offspring. Anders Nilsen, Shary Boyle, and David Heatley contribute stories of a similar ilk.

Conrad Botes

There's also a great deal of surreal fantasy in Kramers Ergot 7. CF delivers a two-page strip which will appeal to those who enjoy his Powr Mastrs series. Will Sweeny works in roughly the same territory, imbuing his tale of monster invasion with very cool character design and beautiful, gossamer linework. Matthew Thurber chronicles Brian Eno's work producing an album of songs written by the resurrected corpse of Michael Hutchence. (I'm struggling to explain exactly how much weirder (and better) the actual strip is than that description.) Florent Ruppert and Jerome Mulot's two-page story is surreal and highly effective; the large panels convey the enormity of a staircase which various figures are scaling. And the art, black and white with hundreds of evenly-spaced, short, vertical lines, really stands out in a book filled with violent displays of color.

Matt Furie's story is handsome and disturbing, particularly for those who have read Boy's Club--the good-natured anthropomorphic burnouts are now killing and enslaving each other. Ted May's "Cradle of Frankenstein" has a more straightforward narrative than many of these stories, but the layout is daring, every bit as good as you'd expect from someone who included a Slade-themed pinball machine in the last issue of Injury (RIP).

Matt Furie

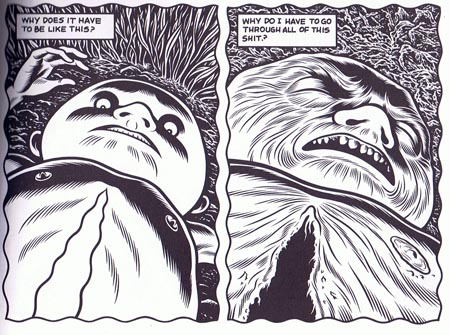

Probably the best of KE7's fantasy comics--and actually probably the best thing in the book, period--is Josh Simmons' extremely dense 3-page comic, "Night of the Jibblers." The pacing is extraordinarily effective, building a great deal of tension for two payoffs, each of which floored me for very different reasons. Just as remarkable are the Jibblers, some of the most memorable creatures I've ever seen on a comics page. No spoilers here; you really need to read this story if you have any interest in the genre. I'm not at all exaggerating when I say it's one of the best horror comics I've ever read. I'm now wondering if Josh Simmons might be the most underrated active cartoonist in the world.

Two other contributions bear special mention. While not rooted in fantasy per se, Gabrielle Bell's deconstruction of the espionage genre is a career highlight. By eliminating any trace of motivation from the protagonist, Bell exposes the absurdity of the spy thriller, while simultaneously distilling its appeal to its base elements (eg, exotic settings and murder). The monotony of the 8 x 8 grid enhances the effect. It reminds me a great deal of Richard Sala's shorter work, except Bell plays it the whole thing perfectly straight.

Editor Sammy Harkham provides as fitting a cover for Kramers Ergot 7 as one could hope for. The image depicts a post-apocalyptic colony, but it's somewhat unusual in that it's less of a wasteland and more of an idyllic pastoral. Storefronts on what used to be a city street are coated with vines and moss, but life continues to thrive; young women sit in communion with nature (one's even hugging a deer). Harkham's cover hints at the nature of the culture these human survivors have constructed. First, they're all female; the lone male figure is a cadaver in a car which is in the process of being coated in green. All the women are unclothed, except one figure who appears to be receiving oral sex from another figure (whose genitals are obscured by a group of passing ducks, adding a further note of ambiguity--maybe there are men in this world after all?). Only one storefront isn't covered in vines; rather than a store name, there is an ambiguous image which might possibly be of religious significance. Water is flowing out of its window display. The most dominant aspect of the composition is the black sky, taking up the top third of the picture and making the whole image quite ominous.

Sammy Harkham

It's a terrific illustration, and an appropriate one in a few of ways. Like many of the stories within the pages of KE7, the cover is extraordinarily dense, providing a great deal of narrative meat in what amounts to a single panel. Furthermore, the image of a post-apocalyptic city street inhabited by naked women and wildlife actually gives you a good idea of what you'll find within: haunting, off-kilter fantasy. Finally, one of the women is reading the comics section of a newspaper upside down, thus undercutting the grandiosity of the whole Kramers Ergot project.

That's the thing which might surprise all those who were inexplicably angered by the very thought of a $125 anthology: this is not a pretentious, ponderous book. Many of the stories are quite funny. Johnny Ryan's strip, "My Sexy History," mocks the most famous work by fellow contributor David Heatley--which itself appeared in a previous volume of Kramers Ergot. And it comes a mere three pages after Heatley's story in this volume!

Kramers Ergot 7 is, for my money (all $125 of it!), the best anthology of the last decade. It's also the most impressive monument to comics as a form of art. Those enormous pages do absolutely make a difference, both for the opportunities it provides the cartoonists and the overwhelming effect on the reader. Several contributors turn in the best work of their careers. I only wish I could afford to buy a copy for Alan David Doane.