Abhay: Inquisition- Detective Comics #35 & #36

/Intro text! I love it! This is the 5th in a series of question-and-answer sessions about recent comics. The same 10 questions get asked in each installment of this series; the answers are sometimes different, except when I get sleepy, then I just copy-paste and hope no one notices.

Past installments have been about The Valiant #1, Bitch Planet #1, Rumble #1, and The Names #1. This week breaks from the all #1 issue motif that had been going before, so that I could try out a complete two-part story. How exciting! INTRO TEXT!

10 Questions about DETECTIVE COMICS #35 & #36 by Benjamin Percy, John Paul Leon, Dave Stewart, Jared K. Fletcher, Dave Wielgosz, Rachel Gluckstern, and associates.

A basic description of this comic, so that everyone's on the same page.

Writer Benjamin Percy describes his fiction as typically concerning "bigfoot and bearded ladies, horse ranches, marijuana colonies and elk-hunting resorts." This two-part story features none of these things -- instead, Batman tries to survive a disease outbreak that erupts at an airport after a mysterious plane crash.

The Batman fights a cold. With his bat-fists.

I couldn't find an interview about these comics, so here's Percy taking to Guernica about his work as a journalist:

"One of my assignments was to check out 'what was really happening' in the nightlife of this city. So I went to an S&M club where people were dancing in cages and there was this giant medieval-looking wheel you could get strapped on for a whipping. I hit a lot of locations like this, one of which was an underground thrash metal club. It was full of dudes with shaved heads that revealed the tats on their scalps. When I walked in, the band was raging and the mosh pit extended across the entire dance floor. The ceiling was low with exposed pipes and timbers—one guy with a massive mohawk was hanging upside down and punching people while they punched and kicked him."

QUESTION 1.

Is this comic about anything besides its plot?

The first part is a spectacle-driven set of reveals, all plot hooks. But in the second issue, there's some small divergences from that plot: a little essay about airports as metaphors for life; a (extremely ill-timed) 24-style War on Terror torture bit; a little sentimental essay about death, near the end; arguably, an extended detour to a S&M club (which has a plot function, but is so wedged-in and amusingly out-of-nowhere that it seems almost churlish not to mention here).

It doesn't quite cohere into being a whole piece. It doesn't quite manage to have a point. The writing definitely face-plants when it tries to pretend that the story was about something, a badly misfired attempt to tack on a gooey Hallmark ending onto a story about bioterrorism.

Tangent: Speaking of Batman, the ones I grew up on and remember most fondly that weren't by Frank Miller, they were all by Alan Grant and Norm Breyfogle, so I should probably mention here the fundraising efforts that are underway for Mr. Breyfogle who's suffered health issues recently, in case news of that got by you and you have similarly warm feelings towards that run. I especially like the issue where Batman pointlessly fights a white tiger for no reason, and it very nearly ties into my next point, sort of.

It succeeds more when it's an empty exercise in style. That's probably true of all of the Batman comics I bother remembering. Style is that character's greatest virtue -- that character has invited a range of styles that just isn't true of other characters in industrial comics; that isn't true of all that many characters outside of such comics, either. It doesn't make me want to read comics regularly about that character any more because holy shit am I ever bored of hearing about the Batman. But when it's a creator whose work I enjoy enough to not even care what they're working on, just to see them work (here, John Paul Leon), when they want to get paid, and put out a Batman comic? I can least ask myself "what will they bring to that character" in a way that I don't think is true of any of the other paycheck characters in comics (e.g., Wolverine, Spider-man; who else? Hellboy?).

Anyways, Simonson-Goodwin Manhunter is a style exercise, but it's a stone-cold killer, as good as it gets. Who even remembers the plot to Manhunter? There'd be no point to -- I remember that fight at the cathedral, instead. There's worse things to be in the world than stylish. This comic, when it tries in its last page to convince the reader it told them some sappy story about a grizzled war-vet Airport Cop, it's not so hot. But that out-of-nowhere bit set at a S&M club? It wasn't enough, but I thought that was a nice try, at least. I wish they'd gone further in that direction. (For example: spanking and blindfolds...? #notmyChristian)

QUESTION 2.

Did the creative team make any interesting choices in the visual presentation of the story?

(The bit where I gush about John Paul Leon: Let me just get this bit out of the way, but man, That Fucking Guy. He understand light; he gets a lot of ink on a page without pages being drowned in the blacks, without it becoming murky, without the action ever becoming unclear. He can draw with a thin line and detail the hell out of a moment, then in the next panel go full-blown noir and tell the story in only slices of light. But his lighting choices, there's usually a storytelling reason-- he's not just showboating. His stuff is detailed without feeling like any linework is there for no reason. There's always a feeling of a human hand with his work, some other person in the world who put ink on paper just for you. In these comics in particular, he goes from massive early-00's-comics spectacle to more classical the-Batman-lurks-in-the-shadows moments, and it's still all somehow a consistent experience. I mean, shit. Shit, I just think that dude's good at his job.)

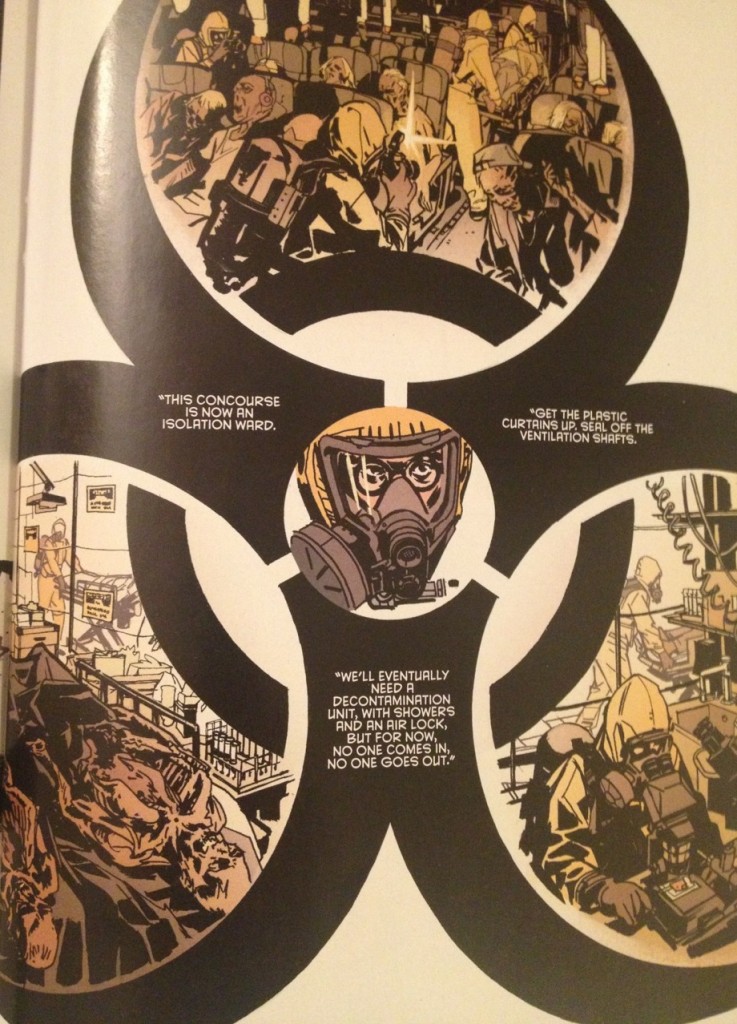

A design-heavy page from the second of the two issues.

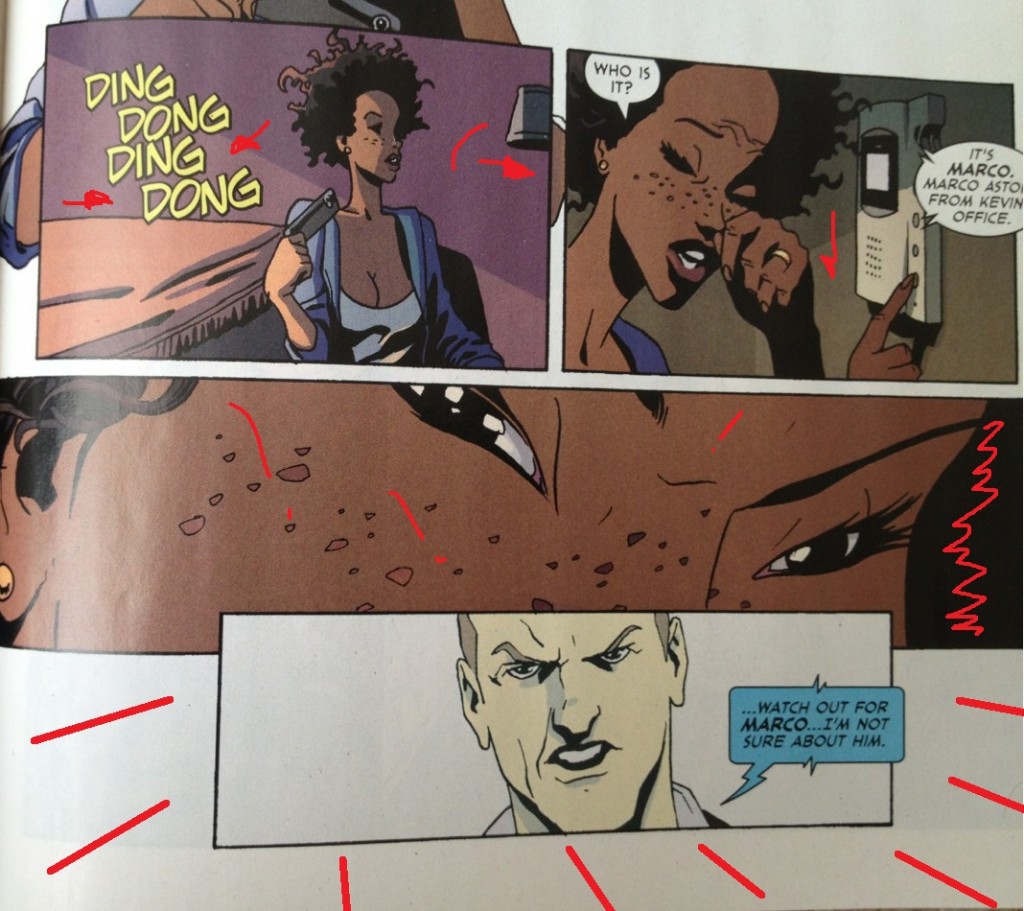

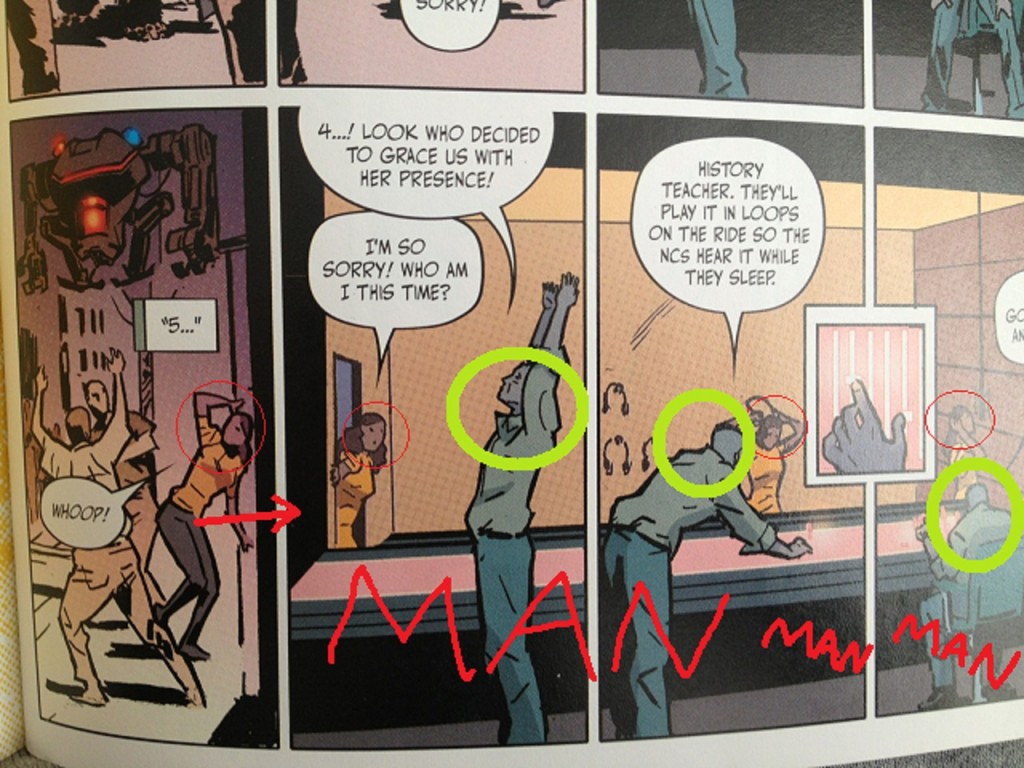

Here, while many of the pages are dominated by standard Batman adventures, the comic still gives the authors plenty of opportunity to show off visually: a page where the panels are set within the negative space of a biohazard symbol (with the head of the character who has imposed that quarantine superimposed above the symbol's center, with the panels showing the results of his action orbiting him, conveying the hierarchy of the situation both through narrative panels and through a recognized symbol); an early page with a "procedural" quality, depicting airport security locking the doors for a quarantine; a page of Nightwing stalking through a fenced-splash page of the S&M club (particularly, the momentum that they create by placing a tiny figure of Nightwing at the bottom of each of the three panels of the fenced-splash).

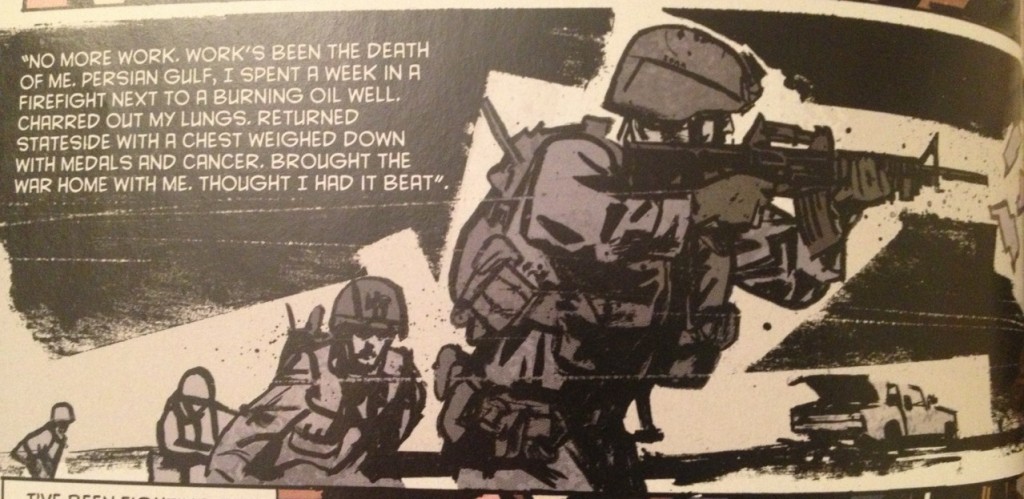

A one-panel flashback to Airport Cop's war experience. For only this panel, Leon breaks from the visual style of the rest of the comic, and gets closer to something like a Daniel Zezelj panel. I like how you can feel that texture of Leon drawing a razor blade across the ink for those small white lines (wild guess). What's most notable are those black abstract shapes that suggest chaos, violence, ruined buildings, but are just abstract black shapes on which narration can be stated without the clunkiness of word baloons. It's a shame they only pull that move out for the one panel.

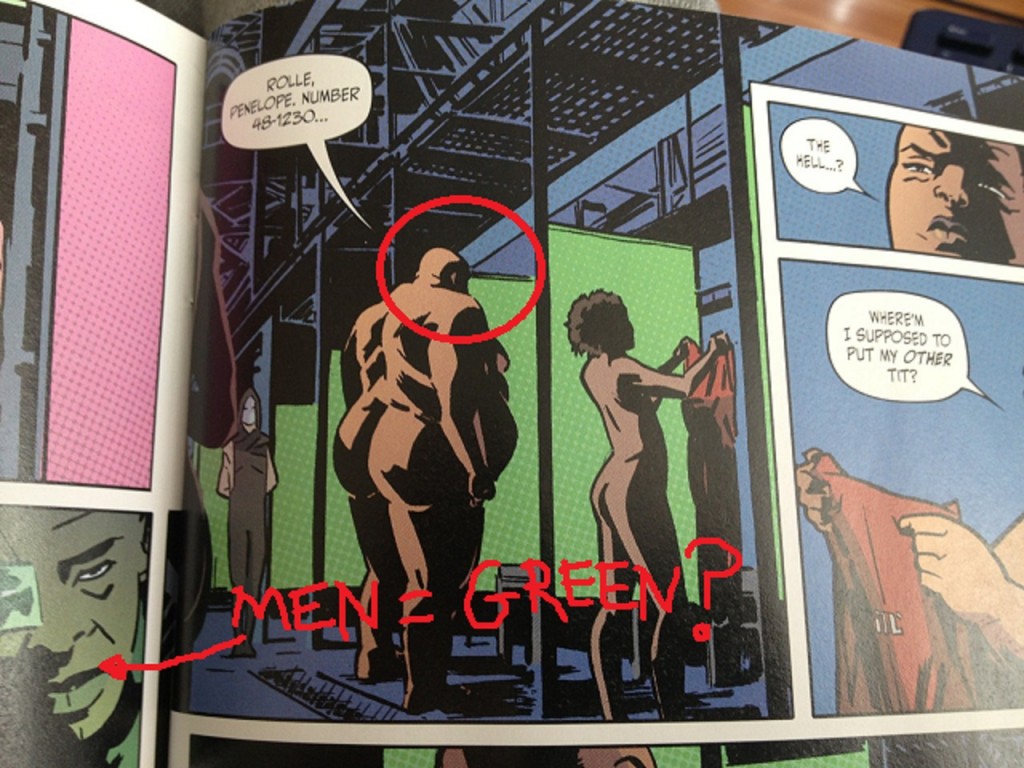

Environments are somewhat color-coded to help the reader locate themselves: the airport is bathed in a dull yellow-grey-brown mix; Gotham outside of the airport, just after sunset, in oranges and purples; that S&M club in red and purple; air-traffic control and a diseased airplane, in green. Basically, out-of-the-airport? Vivid colors. In the airport? Institutional colors. I imagine the colors help readers want to get out of that airport, just like the Batman.

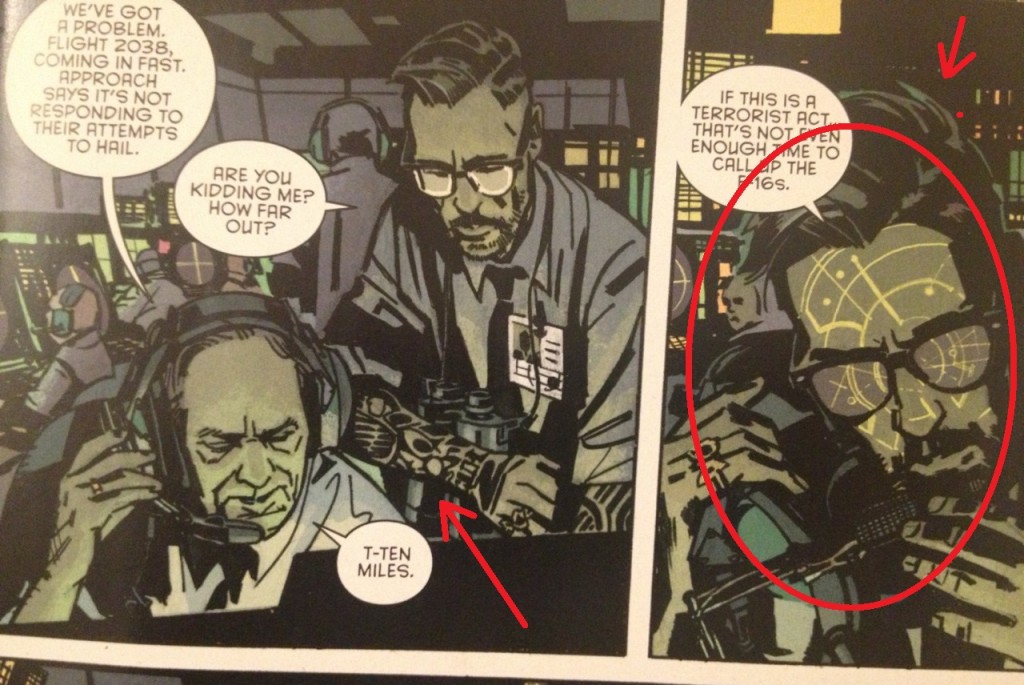

Use of color as detail, in this bit -- air traffic control displays lighting a face. Note the arm tattoos: this isn't even a major character in the comic, but he is nevertheless visually interesting.

QUESTION 3.

How is the comic structured?

One story over two issues. If you wanted to break it up into a three-act structure, I'd figure issue one is Act One (a diseased plane infects an airport), while the second issue is Acts Two (things get worse as an uncaring bureacracy takes over), and Act Three (the Batman beats the shit out of somebody, Batman-style).

I don't know that's how I think of the story, though, as there's no noticeable character arc or theme at play here, no catharsis either aimed for or really expected. I just think of a comic like this more as being structured like a joke, setup-&-punchline. Setup: Batman gets sick because of a bad guy (issue one). Punchline: Batman hurts the bad guy until Batman feels better about himself (issue two).

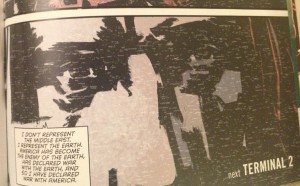

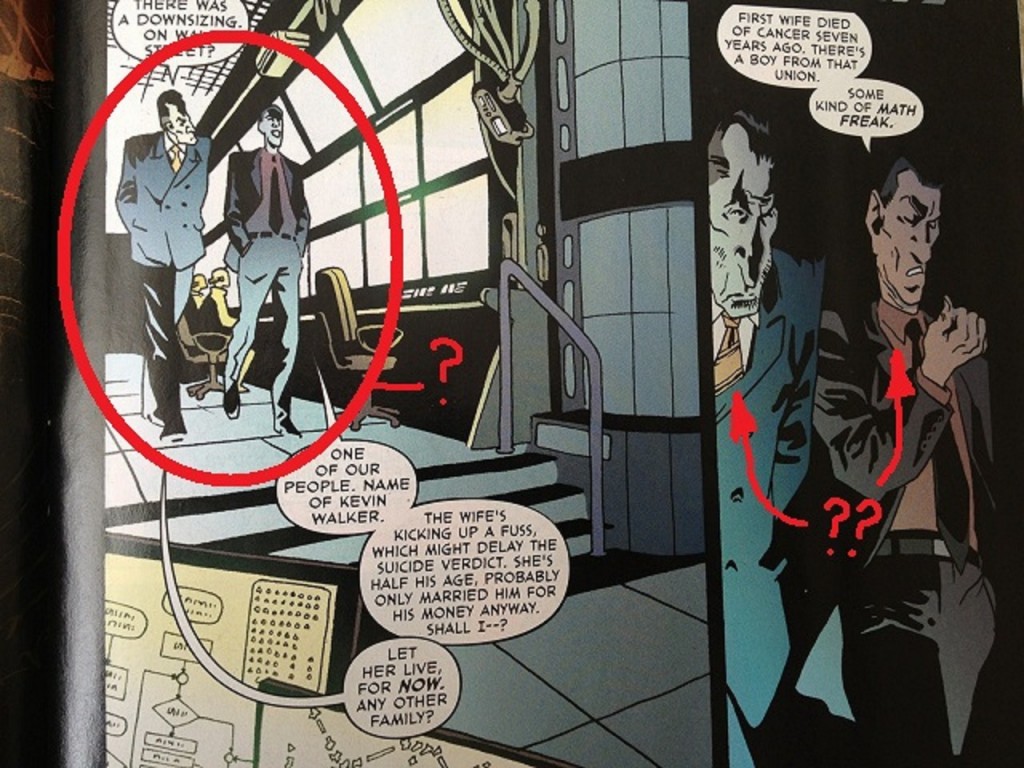

Not much of a cliffhanger inbetween issues: the story break upon the reveal that there is a villain responsible for the virus attack, some white guy with a beard. This information is conveyed by a television broadcast. Usually people will ground their last page cliffhangers on a character the reader cares about reacting to information, either verbally or through a reaction shot or both; Naoki Urasawa is particularly fond of throwing in reaction shots on his cliffhanger pages, say; Brian Vaughan likes a "Shit just got worse" final splash page; there's the often-ripped-off Mark Millar splash on a line promising a future issue filled with Big Action. Here, the issue break dialogue is just a television broadcast of Mumford & Sons speaking in an undisclosed location saying "I don't represent the Middle East. I represent the Earth. America has become the enemy of the Earth, has declared war with the Earth, and so I have declared war with America."

A little underwhelming.

It's a question how much Batman actually motivates the story or its conclusion. Batman doesn't really do anything in issue one other than just provide exposition. In issue two, the Batman just calls up Nightwing, and Nightwing runs around beating / kissing information out of people. The bad guys aren't uncovered by Batman -- after hearing the Batman's around, they just decide to reveal themselves, at which point, the Batman magically appears and damages them.

If you picked up the Batman comic in order to see the Batman be cool or effective, I don't know that you actually got that from this story.

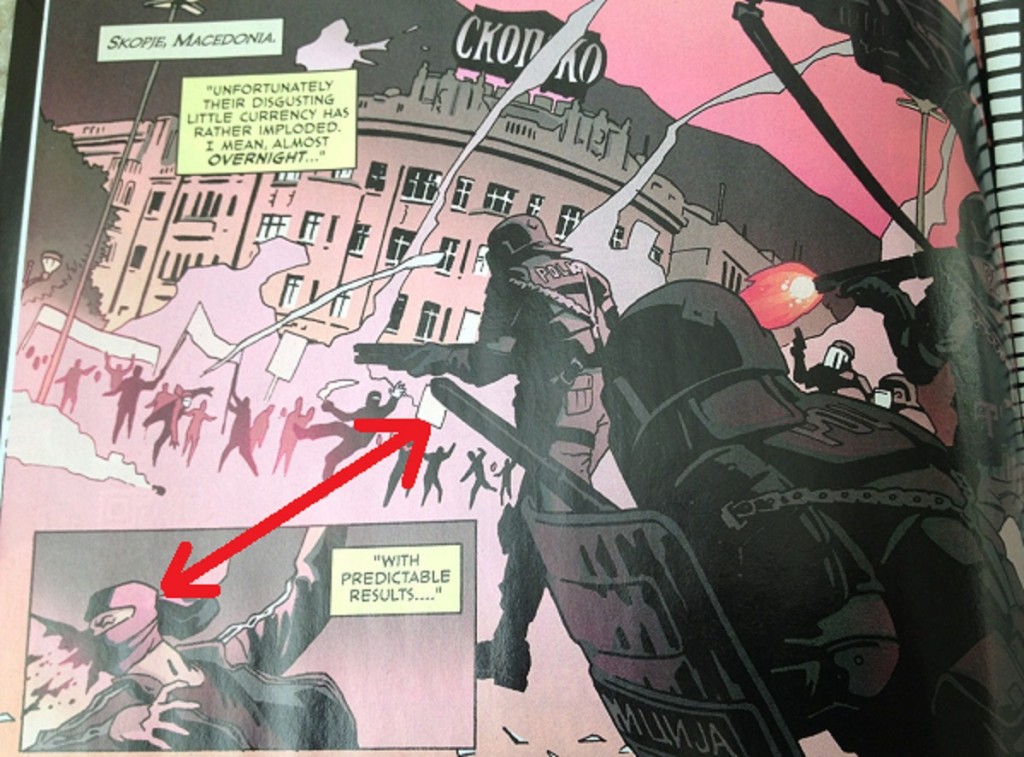

Another choice the authors make is that the story doesn't stick to the point of view of those in the airport. Rather than attempt to be a claustrophobic story about Batman trapped in a quarantined airport, a sizable chunk of part two instead takes place in Belarus...? Batman calls up a torture-happy post-911 post-24 version of Nightwing (really??), and several pages are from his perspective. For a survival horror comic (which is the kind of comic a story about a bioterror-attack calls to mind), it seems unusual to break point of view so drastically.

Since it's two issues, counting pages doesn't make much sense and isn't worth the time, probably. That said, issue one has noticeably longer scenes: most prominently, a plane crash sequence that lasts about 6 pages (and really seems to have been this comic's true raison d'etre, more than anything else). Issue two is much more to the point, broken up mostly into 1 page units, with a couple bits lasting 2 pages. I think the longest chunk of issue 2 is the three-page chunk of Nightwing infiltrating the S&M club...

QUESTION 4.

Is there anything noteworthy about the cover, logo, lettering, or design?

We'd noted above how the narration for the war flashback was put on top of abstract shapes that served a storytelling function. With Leon, the letterers often lay down narration in negative space. When they do use caption boxes, the caption boxes seem more planned than is often the case -- they keep the caption boxes taught against the panel border. I really wish people would do that more, if they could: there's less the sense of the caption box being the writer intruding upon the comic, more of a sense of the writer being invited into the comic by the artist.

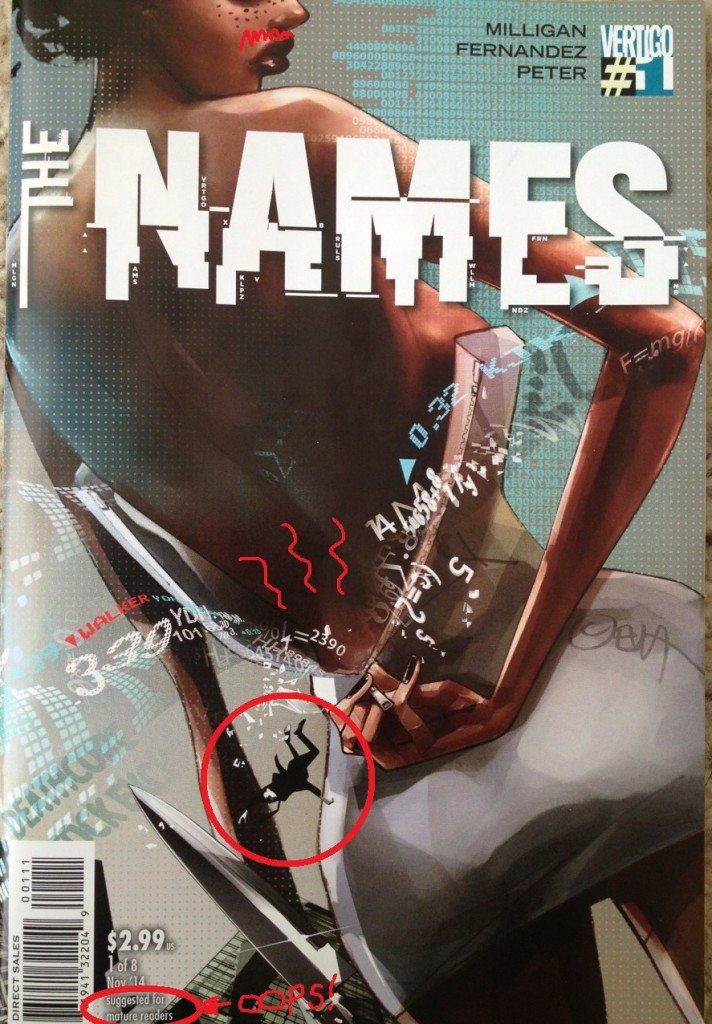

Also noteworthy: the cover to the second issue spoils the ending of the comic...? Say whaaaaaaaat?

From the lengthy plane crash sequence in the first of the two issues.

There's few sound effects in this comic, but I especially liked this panel where Leon diverges from the cinematic mode of the rest of the airplane crash sequence and just draws a more abstract image of glass shattering, presented in black and white. I like how that panel acts as a sort of sound effect for the sequence -- it's almost like a cymbal crash. It's a drawing purely of the sensation of the moment, rather than the moment itself. Very effective.

QUESTION 5.

Is anything about this comic interesting politically, socially, or from some other frame of reference?

The torture-as-entertainment bit, but I can't pretend to be too angry about it. That kind of shit was just past its expiration date before that CIA torture-report came out. It wasn't upsetting -- it's just dull now. Which is probably the more upsetting thing, having something so awful become so normalized.

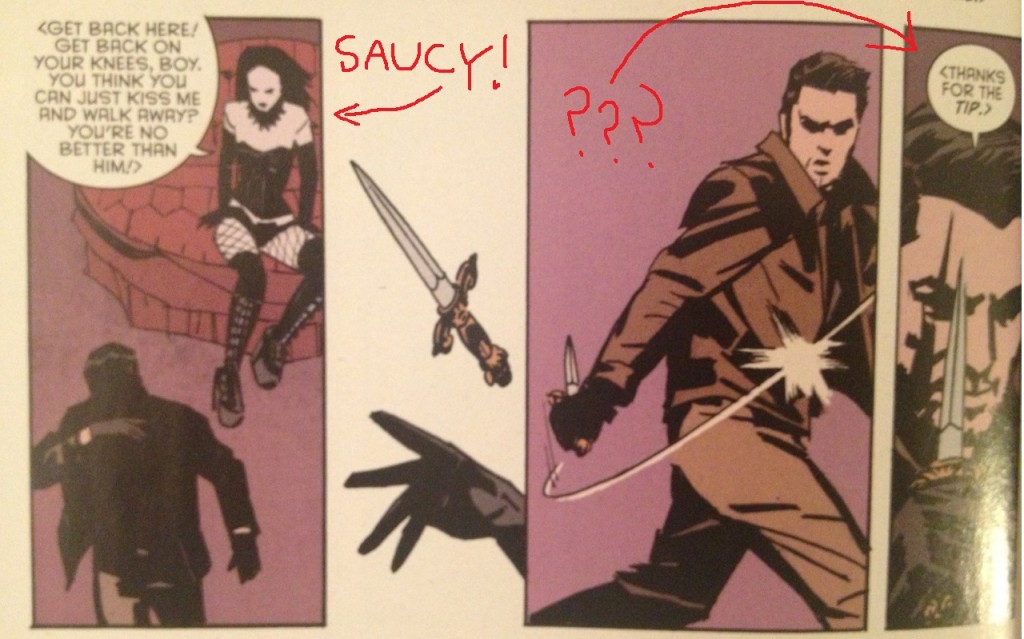

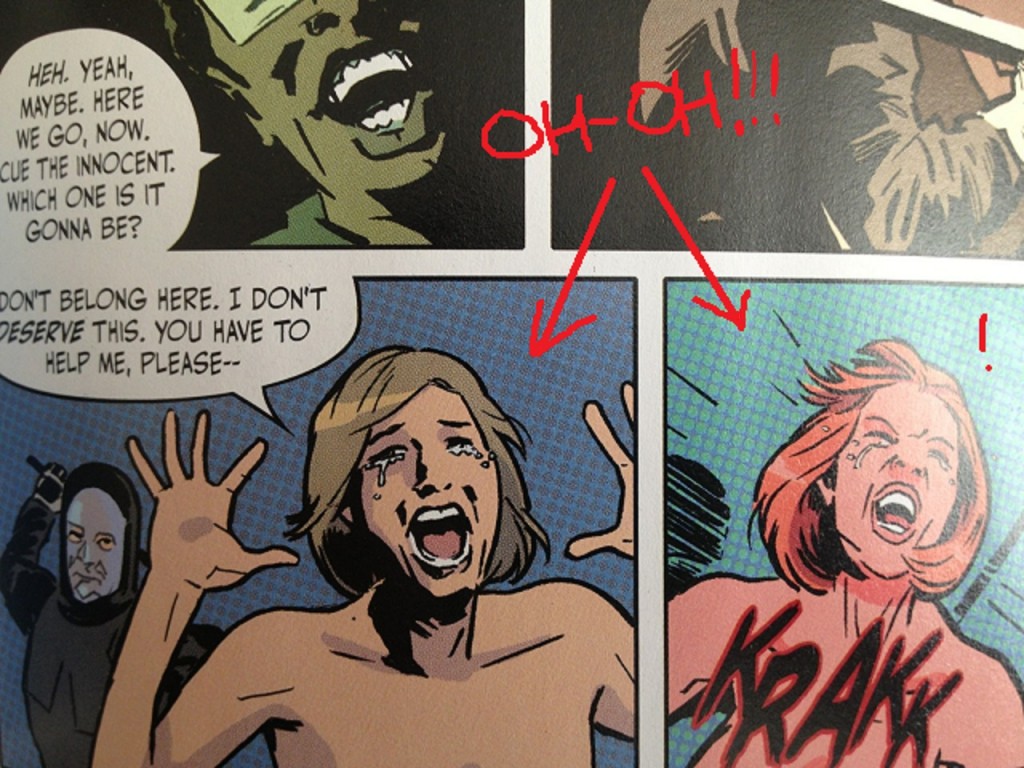

I was more struck by that scene of Nightwing having to seduce information out of a dominatrix.

Nightwing having ladies force themselves on him -- wasn't that a thing...? Also: uhhhh, why was that a thing?

It's a pretty cornball scene -- I grew up with Chris Claremont X-Men comics so S&M in a superhero comic was old news to me when I was 12. Deviant sexuality in a DC Comic -- that's all DC Comics do anymore; I'd be more shocked if Superman talked about liking the plain-old missionary position, at this point. If you told me that the New 52 version of Superman asks whoever he dates to wear a strap on and force him to fellate it, I'd still be more upset that he's dating Wonder Woman instead of Lois Lane. (Because that's just gross. #notmyChristian.)

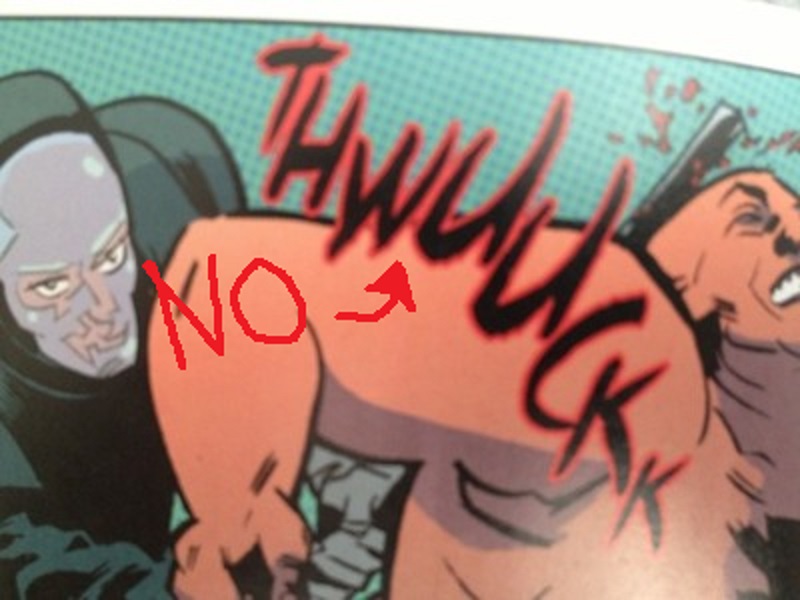

But anyways, Nightwing has to get information out of a dominatrix; she makes him kiss it out of her; he reluctantly agrees, but as soon as he gets the information, he's like "fuck you, lady" and leaves. So, she throws a knife at him because she's so worked up by her lady hormones, and he laughs at her because she's a silly girl and he's a heroic man.

Romance Comic.

Nightwing then runs away from a girl who likes kissing so he can go back to inflicting pain onto the testicles and nipples of other men, which is completely not sexual, nope, not sexual at all, get your mind out of the gutter.

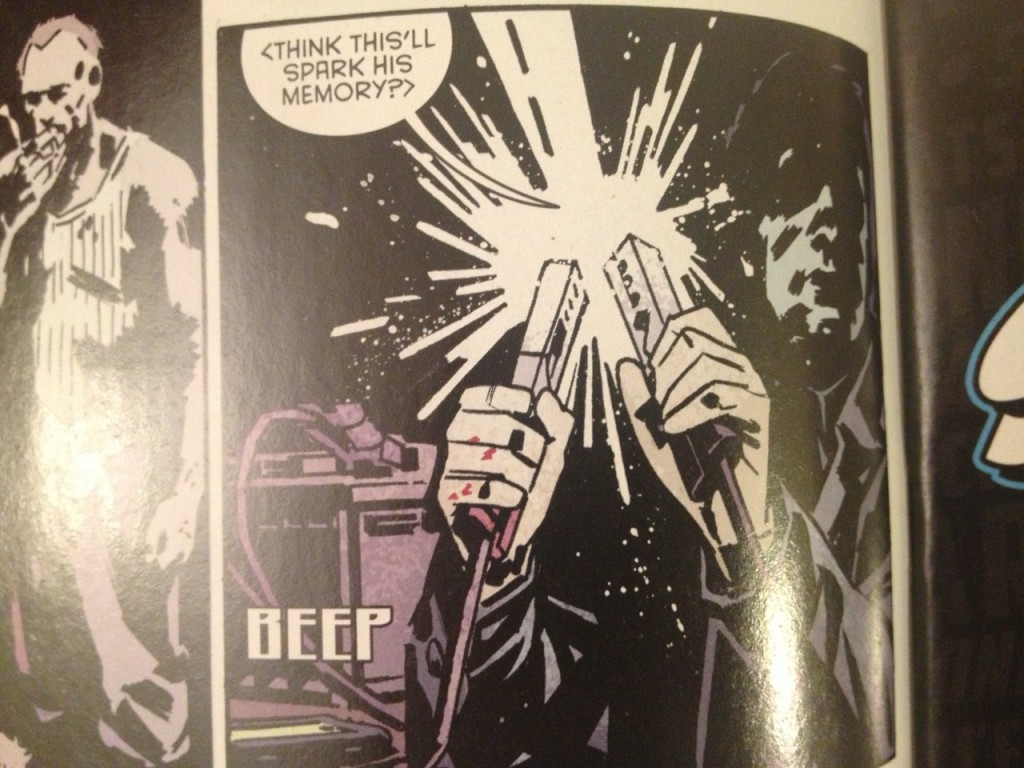

BEEP = Sound effect of Nightwing getting a CBT-boner.

What's striking about this scene isn't that it's unusual for a Batman comic. What's striking is that this is pure, classic Batman. That scene I just described? That's every Batman-Catwoman scene ever. That's their entire relationship, as depicted in roughly 12 billion comics.

"Silly woman, trying to give me an erection. The ejaculation of violence is the only release I need." -- All Batman Comics Ever Made.

Why the hell is that such a Batman thing? Do you know why people like that stuff? I have no earthly idea, but you know: I'm kind of weird in that I kind of like kissing...? I like the part where you're all kissing a lady, and she says, "You don't know what you're doing, do you?" and I say, "Actually, I do: I'm pleasuring you." I find those moments in life very erotic, like Max After Dark erotic, and I don't know why the Nightwing character can't get on my level.

I think that I understand that people like Batman for the same reasons I like James Bond movies: getting to jerk off to a cartoon of male hyper-competence. But James Bond, that hyper-competence manifests in the fact he regularly sexes up ladies...? James Bond will kiss a girl and not act all shitty about it. If you're a spy lady named Candy MadeOfDogshit, there's a 100% chance that James Bond will walk right up to your face and be like, "You've got a weird last name-- check out my boner. Take a photo of my boner with your spy camera." James Bond creates a hostile work environment based on gender for his female colleagues in the spy industry, and we love him for it.

But not Batman. Why is the ultimate definition of male hyper-competence where comic books are concerned so ... not just incompatible with sexual desire, but so weirdly dismissive or hostile to it? And why is that such a big part of the appeal of these comics? It's a more enduring quality of a Batman comic than the fucking Utility Belt, at this point!

(Granted, there's Iron Man, but Iron Man is a guy who basically fights evil in a technologically advanced body-condom, if you think about it, so it's not like we're out of the woods there, either)(haha, "wood").

The comic is also sort of suffused with... you know, if you subscribe to the idea that masculinity is a basically ridiculous performance, just this kabuki we're all trying to pull off... Well, I think that I'd place a small wager that the people who made these issues don't really subscribe to that idea...? There's this fog of fake-ish machismo hanging over everything, though that may just be in my head. All that stuff with a war vet telling Batman How to Be a Real Man, though. But two issues isn't a lot to go on, maybe too few to judge that way.

QUESTION 6.

Where did I put my car keys?

Your "car keys" are Man. In the morning, you can not find your keys, just as you can not find a baby that is hiding. So then, great, you're late to work -- just like an insolent teenager is "late" to school. When you find your keys, you think "I'm going to buy a bowl and keep these in a bowl". But then you don't ever buy a bowl because you have other things on your mind -- that's adulthood. And finally, you shove your keys into a metal slot. That's just like being an elderly person, the part where you get buried in a metal coffin by your ungrateful children -- but used to start the "engine", the engine on the Next Generation.

Your "car keys" are a fucking Man, dude! Riddle solved! Pay me!

QUESTION 7.

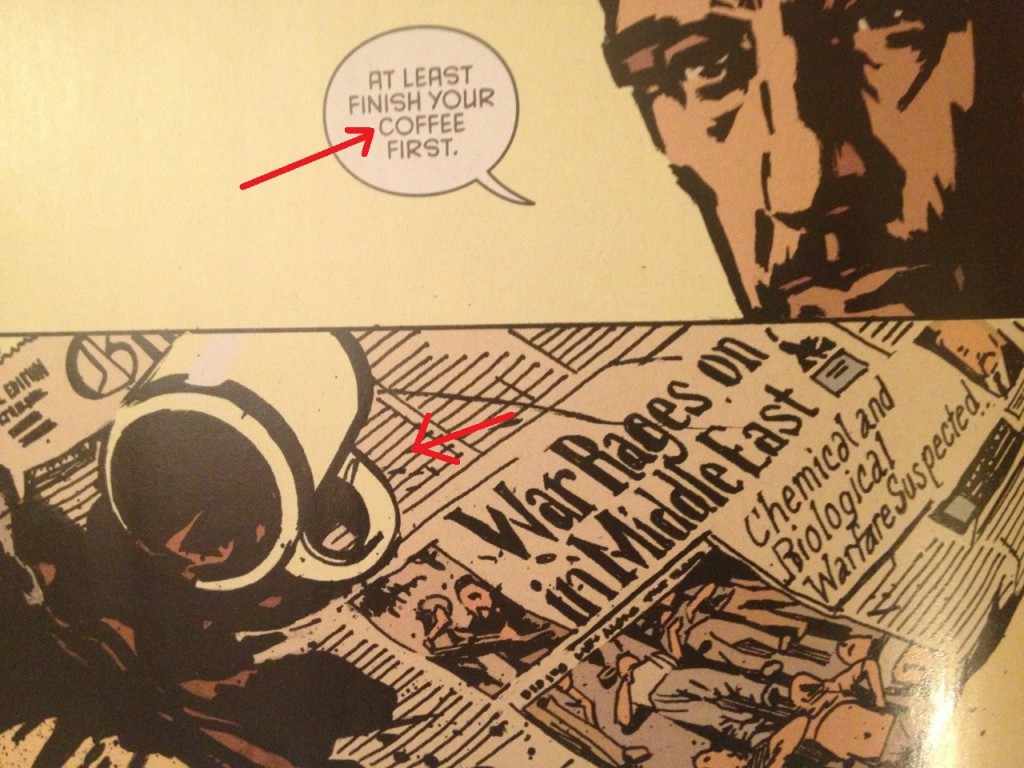

What was the best bit of dialogue in the comic?

The Batman: "What's happened?"

Alfred: "At least finish your coffee, first."

"Fuck you and fuck your coffee, Alfred!!!" -- signed, The Batman.

QUESTION 8.

What is the most interesting page in the comic and how does it work?

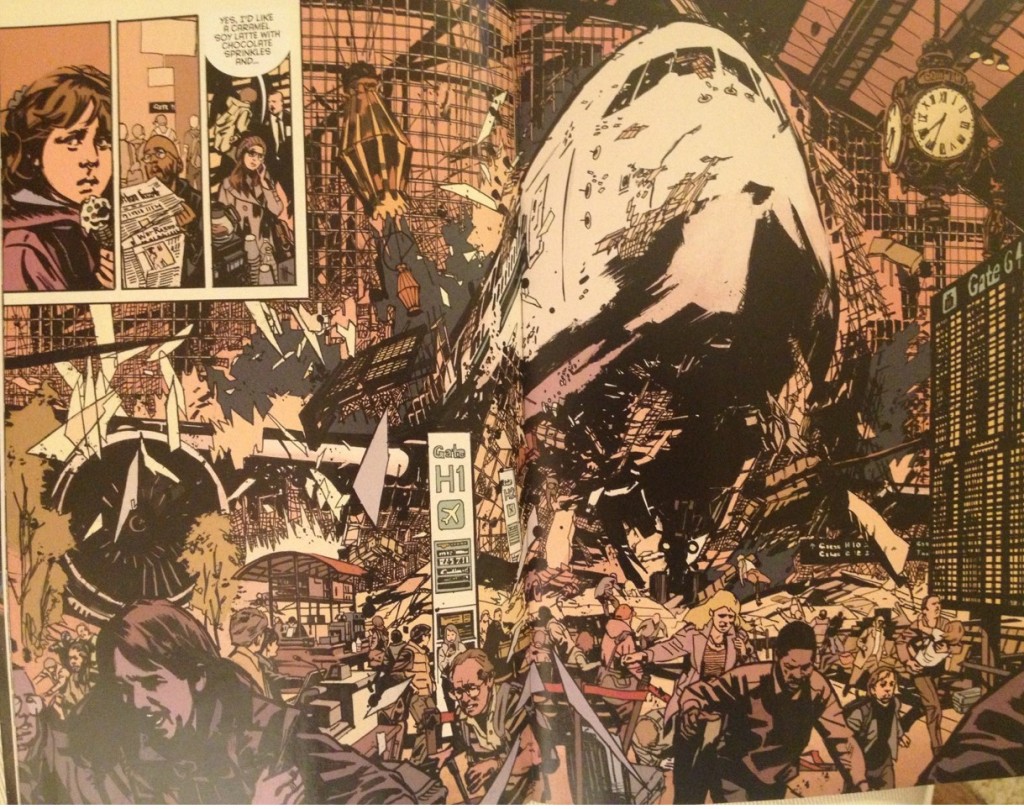

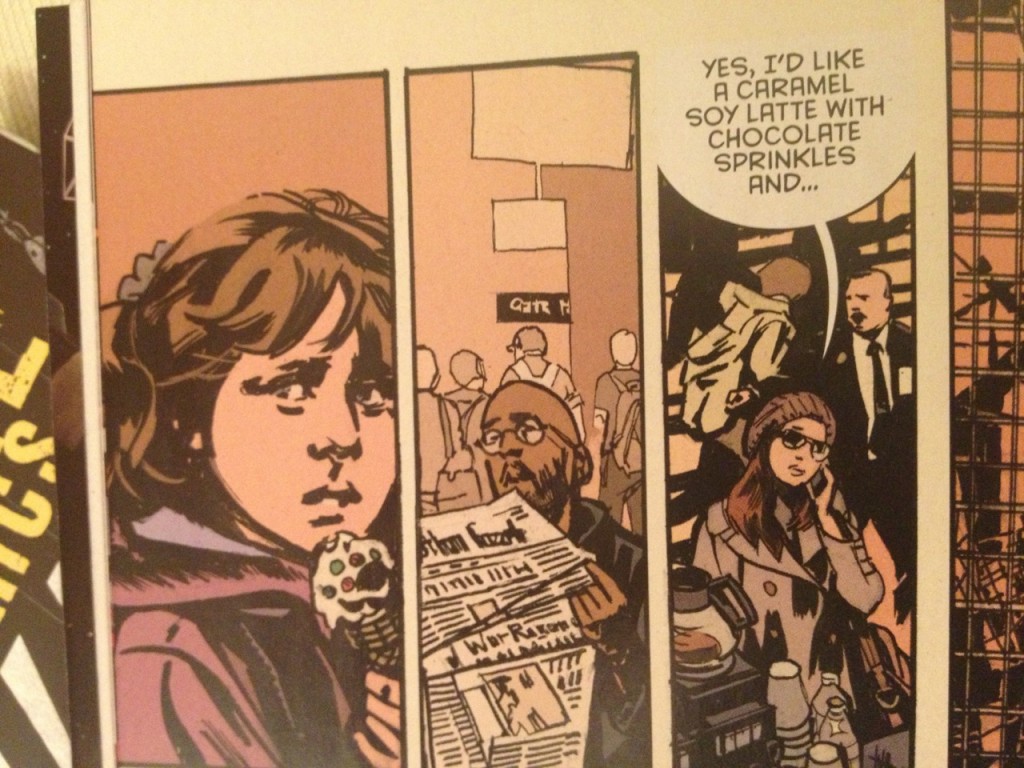

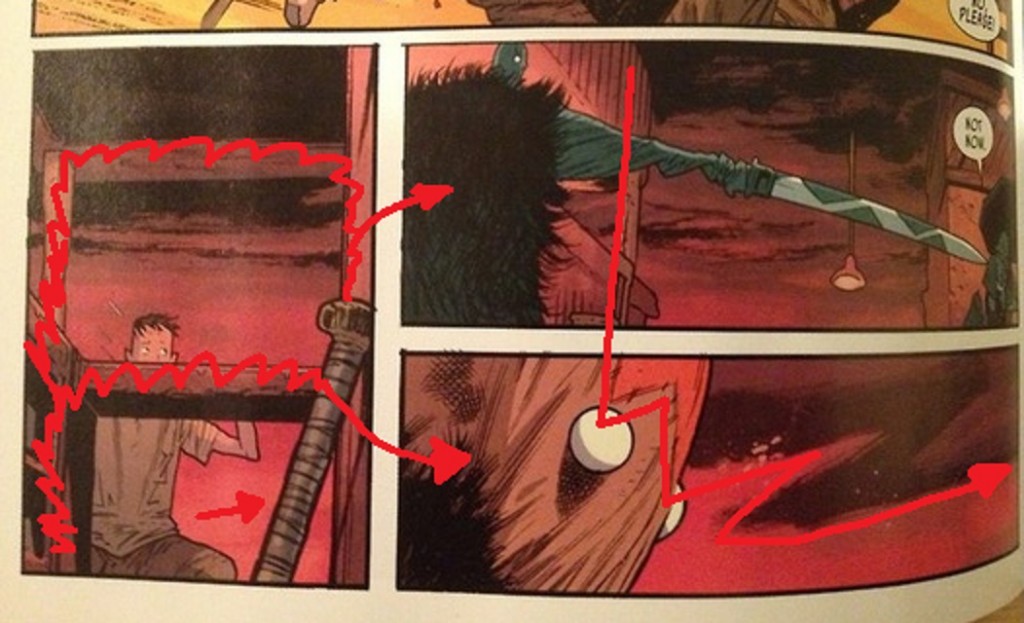

The plane crash in the first issue includes a double-page splash of a plane crashing into an airport, with three inset panels. But before we consider that double-page splash, we should briefly note the two panels that take place beforehand.

In the first panel, "Where the hell's he going?" is stated in the foreground, the plane is drawn in the mid-ground, and the airport is in the background. The panel's composition answers the question posed by the dialogue in the panel.

In the second panel, the viewpoint then changes as the situation has worsened. At least, we know it's worsened because the creative team has exchanged the foreground and the background. Now, the reader's POV is the airport and the airplane is coming towards it.

Even though the plane is located in the dead center of both panels, that shift in POV makes the plane feels "closer". The plane feels fast even though the plane hasn't actually moved on the page. (P.S. comics are magic).

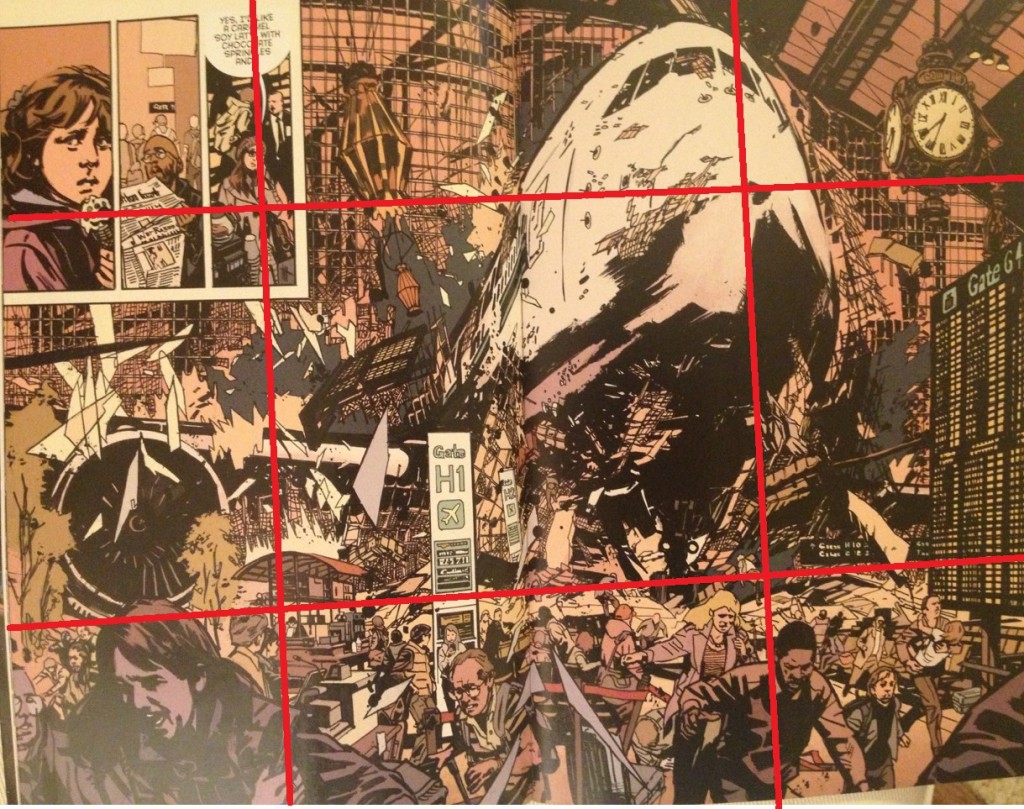

But then, the double page splash.

Spoiler.

It's not just the spectacle of the plane crash but that the creative team does not rely on that spectacle. The authors create small mini-dramas within it, using the three inset panels.

A kid eating an ice cream cone?

That kid's got to run.

A nameless lady getting a latte?

That lady is in harm's way.

(We even continue her story on the next page even though once again, she is not a "character" in any other respect in this comic).

The little kid. Plus, the lady behind him, over by the coffee kiosk. Uhhhh, the black guy probably just dies first -- I don't see him again. Sucks to be you, Black Guy Featured in Any Story Ever.

The point is the action isn't just happening -- it's happening to people, and the creative team makes the minimal effort to care about those people. So when the Batman is trying to save the airport later, we know he's trying to save human beings -- not just objects or architecture.

As for the splash itself, the Rule of Thirds perhaps bears mentioning. Wikipedia:

The rule of thirds is a "rule of thumb" or guideline which applies to the process of composing visual images such as designs, films, paintings, and photographs. The guideline proposes that an image should be imagined as divided into nine equal parts by two equally spaced horizontal lines and two equally spaced vertical lines, and that important compositional elements should be placed along these lines or their intersections. Proponents of the technique claim that aligning a subject with these points creates more tension, energy and interest in the composition than simply centering the subject.

Not an exact measurement, but. Just go along. For your poor father.

Here, the plane crash is roughly at the top-right intersection of Rule of Thirds guidelines. Note that the woman ordering a latte is roughly both at the top-left and bottom-left intersections, i.e. the reader's eyes are in some small way guided to these two locations, and this progression not just a pure game of playing Where's Waldo.

Usually, I want to complain about double-page splashes. Usually, they're just empty spectacles, and I have a very "am I supposed to be impressed by this" jaded and bored reaction to them. This splash, it's spectacle, but it doesn't achieve its spectacle by wholly sacrificing the power of comics. The authors could've just relied on an illustration -- it could've just been the airplane crash and no reader would have ever asked for more -- but they did more than that, went further than that; these are still comic pages. Plus, it's the climax of action and momentum created in prior pages -- it's not just a splash as a cheap way to create excitement that wouldn't have been there otherwise; it's a splash to payoff on excitement that's been built, like the fulfillment of a promise.

(There's a second double-page splash later in the issue that's not half as interesting, a more gratuitous splash that comes without much build-up. So you can see what distinguishes this splash in my mind within the issue itself, if you're, like, some kind of weirdo).

QUESTION 9.

Did you experience any noteworthy emotion reading the comic?

Not so much. Percy's new to the medium (I'm guessing?) and there are kinks to work out, but he supposedly has a reputation as a promising writer. And John Paul Leon is certainly no slouch -- I'm always happy to look at his work, especially in collaboration with a strong colorist like Dave Stewart.

It just didn't seem like either really had their heart in it on The Batman Part.

Leon's best pages involve men in containment suits, airplane's crashing, quarantines being imposed, biohazard symbols; most of the detective work is done by Nightwing; most of the philosophizing is done by Airport Cop; as mentioned before, the bad guy doesn't even get caught by some move made by the Batman -- Mumford & Sons just decides to fight Batman, and it quite predictably goes very badly for him.

But do I find myself wishing Percy/Leon had gotten a chance to do a longer and more considered version of a comic about a grizzled old Airport Cop fighting a terrorist attack, without the Batman...? Well, no. Because I've seen that -- it's called Die Hard 2. (And it sucks.)

They needed to publish issues 35 and 36 of Detective Comics in whichever months these issues were released. So, here are issues 35 and 36. Because that's how it works; that's the business. That's it.

QUESTION 10.

What do we hope that younger cartoonists learn from this comic?

So, what am I saying this week? "If you throw enough pyrotechnics and craft and visual doo-dads at the reader, you don't have to care as much about story or character or theme or having a point!"

[Single balloon falls from ceiling]

Craft has its pleasure. Style has its pleasure. Maybe smart doesn't come along every month, and you still have to eat. "If you don't have a good personality, you might as well at least dress well." -- Your Shallow Grandma (Who Then Also Says Something Racist Probably).

Anyways, a Batman comic is a Batman comic is a Batman comic; if folks wanted story or character or theme or whatever, they probably wouldn't be reading Batman comics. There's no harm to comics like these. Folks get paid while being creative; folks who wants to read more Batman get more Batman; everybody wins, at least from a practical perspective.

But what do we want for younger cartoonists? If you're still young, while you still have some fire in your belly, while you've still got some Awesome Years left in you, maybe try for a little more substance. Probably you'll fail and dishonor your ancestors. But a whole world of Cold Practical Shit's not going anywhere; they're going to need to publish an issue of Detective Comics, that month you give up; there's no hurry. So you might as well give doing something a little more meaningful to you a shot, while/if you can.

NEXT:

Taking a few weeks off, to plan the next round of these and work on some other things. I think the next batch should only be 4 installments -- five in a round feels like too many. I had an idea for the next four, that they'll all be in the exact same genre (I've read at least 4 comics recently that all happened to be in the same genre). If that same genre thing works out, then the round after the next one will hopefully be more of a mix of things -- there's been one suggestion for a Lady Thor comic, so if this goes to a third round, that's coming up. But plans are fluid and we'll see.

Thanks for the kind words on these last five. And Happy Valentine's Day. Be Mine.