Best of the 00s: Black Hole

/ In case you missed my first post, I'm going to devote most of my writing at The Savage Critics to an ongoing project of making a list of the decade's best comics and graphic novels (at least that's the plan for the first year). I had planned on starting with Black Hole and announced my intention to do so at my blog; little did I know that Sean was also planning to look at Black Hole for his inaugural review at this very site! But Sean caught my comment and we convened, deciding that we would both review Black Hole, and then compare notes in a subsequent post.

In case you missed my first post, I'm going to devote most of my writing at The Savage Critics to an ongoing project of making a list of the decade's best comics and graphic novels (at least that's the plan for the first year). I had planned on starting with Black Hole and announced my intention to do so at my blog; little did I know that Sean was also planning to look at Black Hole for his inaugural review at this very site! But Sean caught my comment and we convened, deciding that we would both review Black Hole, and then compare notes in a subsequent post.

Why did we both want to start with Black Hole? I can't speak for Sean (I've made a point of avoiding his post up til now; I'll read it once this is up), but I thought of it as a great way to kick off a column about the best comics of the 00s. Black Hole is generally regarded as one of the great graphic novels of all time, so why wouldn't one consider it for the decade it came out? (Kind of--I realize that half of the original, pamphlet-type issues were published in the 90s, but we'll save any quibbles over that for the comments.) Plus it's a good yardstick for talking about the other comics I'll be covering here--more about that later. The review follows after the break.

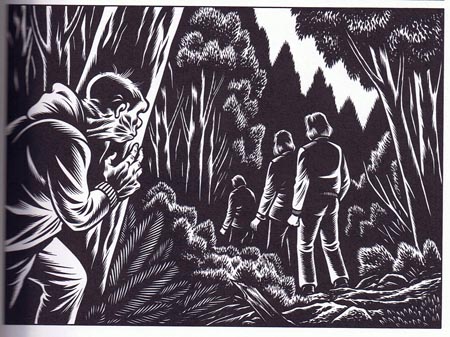

Every time I look at Black Hole, the first thing that hits me is the blackness. Outdoor scenes, particularly those in forests, are common in Black Hole, and play a role in the plot and the multiple, shifting layers of symbolism. But when you first crack the book open, you're hit by the blackness of the woods, trees only distinguished by the slightest slivers of light. It's a primeval forest Charles Burns draws, the woods of fairy tales where wolfs and witches lie in wait for young people.

Which is appropriate, because more than anything else, Black Hole is about the mystery and danger of youth. I don't mean to say Black Hole is a murder mystery, although that's certainly an aspect of it. The mystery I'm talking about is the confusion and frustration that comes with puberty and adolescence. That theme is also apparent from the first pages of Black Hole, in which protagonist Keith Pearson cuts a perfect vagina-shaped hole in a frog he's dissecting in biology class. This causes Keith to pass out, but not before triggering a vision which establishes Black Hole's vagina-wound motif and presages many events yet to come.

But back to the forest. Keith and his friends are smoking a joint in a spot they've named Planet Xeno. Keith is transfixed by the natural beauty of the location, ignoring his friend's story that Rob Facincanni, a popular classmate, has fallen victim to "the bug": an ill-defined STD which turns its victims into deformed mutants. Rob, for instance, has a mouth in his chest that occasionally speaks in a high-pitched voice, often speaking truths Rob wouldn't normally reveal. Keith eventually realizes that they're being observed by someone. They leave the spot to look around, and soon stumble upon the tent and possessions of another affected classmate, Rick "The Dick" Holstrom.

While his friends look through Rick's belongings, Keith wanders around nearby. He finds a shedded human skin, apparently left behind by a female victim of the bug. Keith (wrongly) laments the fact that he'll never know this woman, and is confronted by an especially grotesque sufferer from the disease, who asks (warns?) Keith to "go away." Keith soon realizes that he and his friends are surrounded by the mutated victims of the virus, watching them from within the woods. When he returns to Rick the Dick's campsite, he finds that his friends have trashed it and are ready to leave.

In those first pages, Burns establishes most of the major themes and plot points of Black Hole: (1) Keith's crush on classmate Chris Rhodes, whose skin he found; (2) the distressing nature of sex, both as a source of obscure dread and as the means by which the bug is transmitted; (3) the casual way in which the characters deal with the bug--no one ever speaks of a cure or even treatment, and adults seem to be entirely unaware of it or unconcerned about it; (4) the use of dreams as foreshadowing but also as a way to twist the meaning of previously established symbols or to uncover the true feelings of characters; (5) the role of specific natural locales as symbols of safety and comfort, but also stagnation; and (6) the aforementioned vagina-wound motif (the masculine equivalent being snakes and other phallo-serpentine things).

If that sounds like a lot to unpack, you're right. For those less interested in these themes, Black Hole works as a relatively straightforward narrative--only "relatively" because there's lots of flashbacks and retelling of events from multiple perspectives. That scene in the woods actually takes place around the same time as events from the middle of the book. But it's not hard to figure out what's going on--if you can follow Watchmen, you can follow this--and besides, you have Burns' extraordinary art to enjoy in the process. But even those more interested in Black Hole's surface elements might find themselves pulled in deeper by Burns' heavy symbolism and relatable themes of adolescent anxiety.

(Spoilers follow from this point.)

The story follows the intertwined experiences of Keith and Chris, from their exposures to the virus to their participation in the emerging culture established by victims of the virus (centered around a colony in the woods) to their attempts to escape from their situations. Chris responds more poorly to her circumstances: before infection, she was pretty, popular, and studious (though also a bit of a drinker). She's reluctant to rely on or even socialize with any victim of the bug other than Rob, who infected her in the first place. Her ability to deal with her new circumstances rest entirely in her relationship with Rob; when he is murdered, she essentially breaks down, strongly contemplating suicide at least once. Still, both Keith and fellow outcast Dave Barnes are looking out for her, providing her with the sustenance and knowledge she needs to survive. While Keith is a mostly benevolent figure, however, Dave has actually been manipulating events to pull her towards him, including ordering his friend Rick "The Dick" to kill Rob.

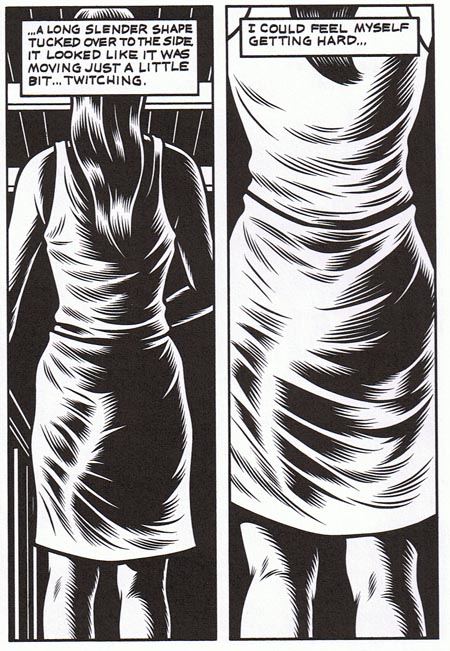

Keith is initially motivated by two occasionally opposing forces: his desire for escape and his desire for Chris. His narration at the beginning of Black Hole suggests this will be the story of how he achieved both goals at the same time, but a trip to buy pot from some college students throws a wrench in his plans. He meets Eliza, a roommate to the students and another victim of the bug; she has a small tail. Rather than revolting him, Eliza's tail (particularly its soft swaying beneath an impromptu skirt) arouses Keith. He's also fascinated by her bizarre art (most of which seems to depict infected mutants) as well as her intriguing maturity ("She knew something. She knew more than I did."). Keith finds himself sidetracked by his growing attraction to Eliza. Yet his compassion for the outcasts, Chris in particular, keeps him grounded in that world as well.

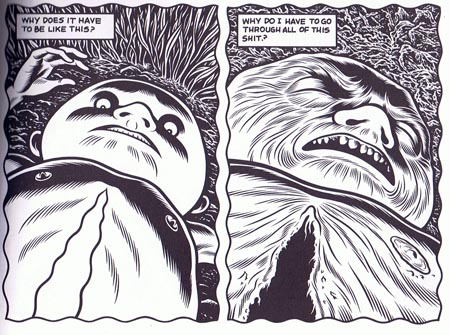

Burns takes us through three of the major anxieties of adolescence: sexual awakening, socialization, and the transition into adulthood. This vision of adolescence is reinforced by Chris and Keith's mutations--skin-shedding and tadpole-like protuberances, respectively. Though they feel comfort in their "natural" environments (the woods and the ocean), Chris and Keith must escape by metamorphosis, changing from undeveloped juveniles to fully-formed adults.

They approach this problem differently. Chris retreats from the challenge, reverting to a more childlike state; she expresses to Dave her wish to undo all the decisions she had made and return to her "boring" life. When Rob is alive, she sublimates her feelings of abandonment and ostracism into their relationship. After his death, she relies on Keith and Dave to take care of her, fantasizes about her parents doting on her. The final scene sees her floating in the amniotic fluid of the ocean, unwilling to leave the womb: "I'd stay out here forever if I could."

Keith, on the other hand, is anxious to move beyond this stage in his life. He irritates his friends with his restlessness, never satisfied with where he is, worried that "This is it...this is all it's ever going to be." When things get difficult, Keith finds solace in green: marijuana and the woods, where he retreats after a bad acid trip. Still, Keith is proactive in dealing with his sexual anxieties, seeking out Eliza and confronting the queasy mixture of feelings he has for her. He accepts the help of the outcasts, and offers help in return. And after "escaping" with Eliza, he plans to move boldly into adulthood, taking up a job and presumably raising a family (as suggested by his tadpole-like deformities).

A third reaction to the traumas of childhood comes from Dave. Keith and Chris try to escape adolescence by moving forward or backward, but Dave seeks to prolong it. Chris sees the bug as tragic, while Keith seems to accept it as a new, permanent part of his life. Dave, however, embraces it, seeing new opportunities in his outcast status. Bullied, belittled, and ignored before his mutation, Dave's isolation from society allows him to ignore its mores altogether. He abducts, rapes, and kills, aided by his friend Rick (who Dave seems to have some control over--he doesn't socialize with the other outcasts, relying on Dave for food and entertainment). In addition to ordering Rob's death, he also destroys Chris' tent in order to encourage her to move in with him. Unsurprisingly, he confesses that he prefers his new life to his old one. But when Chris runs away, revealing the limits to his power, he responds by killing himself and several of his friends.

Black Hole is something of a period piece--look at those hairstyles!--but there's not a whiff of nostalgia to it. The teenage years are something to be navigated carefully, lest one end up "stuck" in the way Keith fears. The first sexual experiences aren't fun--they're awkward and strange, and lead to unwanted side effects. Friendships aren't bedrocks of solace or support; they're motivated by convenience or lust, with the possible exception of Chris' friendship with Marci. And even that relationship is marred by a lack of empathy and casual cruelties.

Keith seems to do better for himself than the other characters, but even then Burns leaves room for despair. Keith's final dream involves him apparently trying to resuscitate a frog-like baby (metamorphosed from his tadpole/sperm outgrowths?) with the same vagina-shaped scar we saw in the first of the book. His friends then show him a yearbook, pointing out that the hideously deformed character who told Keith to "go away" was in fact a future version him, perhaps suffering from an advanced stage of the bug. Finally, he encounters Chris, apparently consigned to the dump heap of his adolescence, sitting naked among the empty beer cans, old magazines, and other pieces of trash Keith has left behind. Having escaped adolescence, then, Keith is rewarded with an introduction to the traumas of the adult world. His sperm/tadpole protrusions suggest virility, but will his offspring survive? And if they do, will they also be mutants? Will Keith be able to recognize himself in the future, after the rigors of adulthood further transform him? Will he always regret leaving Chris behind, failing to save her when she needed it most?

Still, the dream ends on a positive note. Chris pulls a piece of paper out of her vagina-shaped foot wound, revealing a drawing of a lizard (maybe a horned lizard or "horny toad")--an obvious symbol for Eliza. "See," she says, "It doesn't always have to be bad. Sometimes things work out." No matter what the years ahead bring, Keith will always have his time on the road with Eliza. And even though she lost him, Chris will always have her memories of Rob, buried in the sand of the beach to be dug up later.

It's a complex take on adolescence, one which rejects conventional narratives of triumphant transformation, blossoming through acceptance of one's true nature as an individual rather than a stereotype. The nerds don't win--they end up dead. There's no climactic confrontation, only three escapes (counting Dave's suicide). The book ends with the bug still out there, ready to afflict more teenagers. Burns also takes an unusual approach to mystery. Though he does dwell on the Rob's murder and the discovery of various disturbing artifacts (including a disembodied arm), the more important and satisfying mystery comes from the initiations into adulthood that Chris and Keith must undergo.

These complex themes are expressed largely through Burns' repetition of symbols, all rendered in his sumptuous, distinctive style. Burns is one of the foremost symbolists (capitalize it if you want) in comics, earning a place alongside David B., Art Spiegelman, and Chris Ware. He creates a dark and intriguing world, filled with shadows, grotesqueries, and naked flesh. Black Hole is a pleasure to look at, one of the most beautiful comics I've ever read. It's also a dense, challenging narrative which makes good use of the unique storytelling properties presented by comics as a medium.

Not everything I review in this series will prove the equal of Black Hole --in fact, very little will. But I start here because Black Hole provides a model of excellence to which we can hold up other books. When reading other works, we can consider its complex themes, satisfying density, stunning art, and rich storytelling, and realize the potential for greatness in the medium of comics. We can appreciate Burns' deep ambition and successful realization of his specific vision, and seek out works which attempt (and hopefully attain) the same degree of sophistication. It's a high standard, but a lot of comics were published in the last decade. It's entirely appropriate to start with our expectations high.