Old English #2

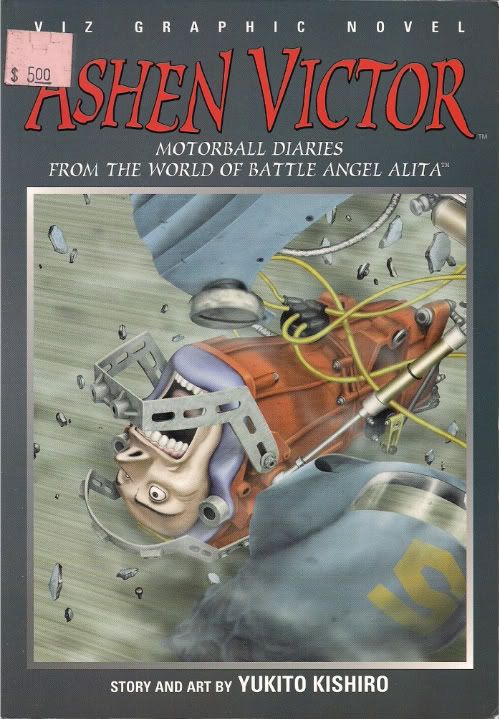

/![]() Ashen Victor

Ashen Victor

Here's a question that comes up every so often: we hear plenty about North American cartoonists inspired by the energy and style of manga, but are there any mangaka crazy about cartoonists from the West?

To my knowledge, the answer is "not a ton." It seems there's some pretty specific, dominant ideas in Japan about how comics are supposed to 'work,' with a strong emphasis placed on visual mechanics. Put simply, Western comics just don't look right, and to the extent there's much of a Western comics presence in Japan at all, it tends to dwell on highly individual stylists as self-contained aesthetic forces. Yet some manga artists draw fabulous inspiration from that area.

This book is one result of that inspiration. I may have obtained it at tremendous monetary cost, but it's no big deal - I do it all for you.

And Yukito Kishiro? Looks like he did it for Frank Miller; I have no evidence, but it could be he devoured every volume of Sin City and still wasn't satisfied.

So he made his own.

Ah, never mind my melodrama. VIZ may not exactly have shied away from Miller comparisons when it published Ashen Victor -- first in 1997 as a four-issue pamphlet miniseries, then in 1999 as a collected book -- but the work itself is thoroughly Kishiro's. Indeed, it's actually a short prequel work to his expansive Battle Angel Alita (aka: Gunnm) saga, a massive sci-fi series that initially ran for nine volumes, 1990-95, and then saw its artist discard the original ending in 2001 and revive the series as a still-ongoing concern (Battle Angel Alita: Last Order) current up to vol. 13 in Japan and vol. 11 via VIZ's English translation.

Ashen Victor appeared between the two major Alita series in Japan, in late 1995; it was definitely not a sprawling opus, in that it consisted of only one volume and focused on the noir-like goings on in the violent armored racing sport of Motorball. It's also conspicuously the only piece of VIZ's Kishiro catalog not currently in print. Maybe some licensing trouble got in the way. Maybe the story seemed too odd for the bookstore-friendly Alita reprint push. Hell, maybe the damned thing looks too American for the market these days. That'd be a laugh.

But truthfully, Kishiro doesn't venture too far out into foreign waters. He certainly ramps up the high-contrast in good Sin City style, and deliberately avoids typical character stylization for a Japanese comic of this sort, yet there remains a suppleness to his backgrounds, a traditional scenery that Miller would strive to dissolve into a thousand scratches surrounding inky gobs. In other words, Alita fans might still admire their familiar world as recognizable, despite the curious perspective imposed on them. It's possibly as much a franchise concern as stylistic one; two reasons for not going too far over the top.

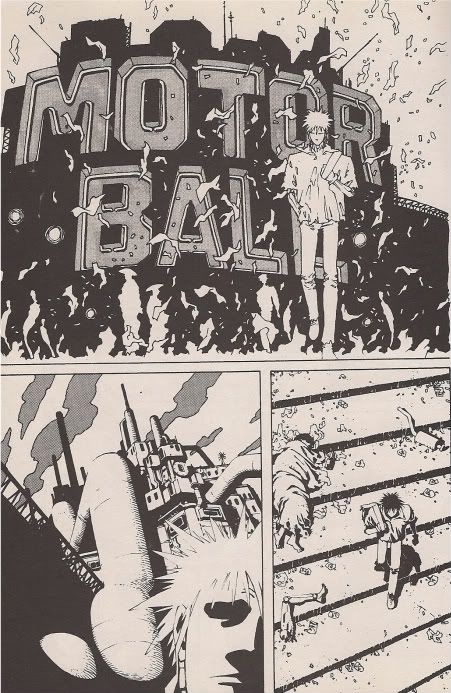

Why, Kishiro even has a spiky-haired hero we all can root for. God, he looks a little familiar, though...

That's right, sports fans: not only is this a Japanese Sin City homage set in the world of ultraviolent cybernetic racing, but one that features a lead gore-spattered cyborg racer modeled after Dream of the Endless. That is brilliant.

Or, at least that's what it looks like; I mean, he does draw in the eyes in a bunch of panels, and hair like that isn't exactly unknown as a boilerplate manga design trope, and I certainly don't have an interview or anything in which Kishiro states "oh, Morpheus, right; great guy, lovely eyes," but the resemblance is simply uncanny.

And it makes perfect sense too, well beyond the Sin City's an American comic, Dream's an American comics character, why not level. I can hardly think of a more perfect example of a writer-driven book than The Sandman; it had some consistent art toward the end of its run, sure, but it largely built its reputation in spite of its irregular visual quality. In the midst of the Image Revolution, it was a beacon of the scribe's victory over fulsome splash page aplomb, and, to my circle of 13-year olds, evidence of trust in the writer over the artist as the true mark of the connoisseur. It was the American way!

Call it projecting (because you could be right), but that's why the Dreamy protagonist of Ashen Victor seems so awesome to me - it's dealing with Sandman on a strictly visual level, ripping out that excellent character design and working the pale flesh and black hair and sunken eyes into the especially black & white contours of Kishiro's pseudo-Sin City, a clever application of visual elements that's indicative of the manga emphasis on the art as the storytelling base. That doomed complexion, that spur of danger... Dream can be noir as fuck!

The plot of Ashen Victor, meanwhile, is a gurgling broth of Miller-approved tactics and general noir notions, like 'fixing the races' and 'fighter bound to throw the match.' Snev (our Dream King) used to be a Motorball prodigy, able to glide between opponents on the track with ease to deliver the ball to the goal. But 17 matches into his pro career and he's best known as the Crash King, the "storm of self-destruction," famous for wiping out in violent, dismembering style in literally every match, to the point where his not inconsiderable fanbase adores him strictly for the spectacular show his body provides while ripping itself to shreds.

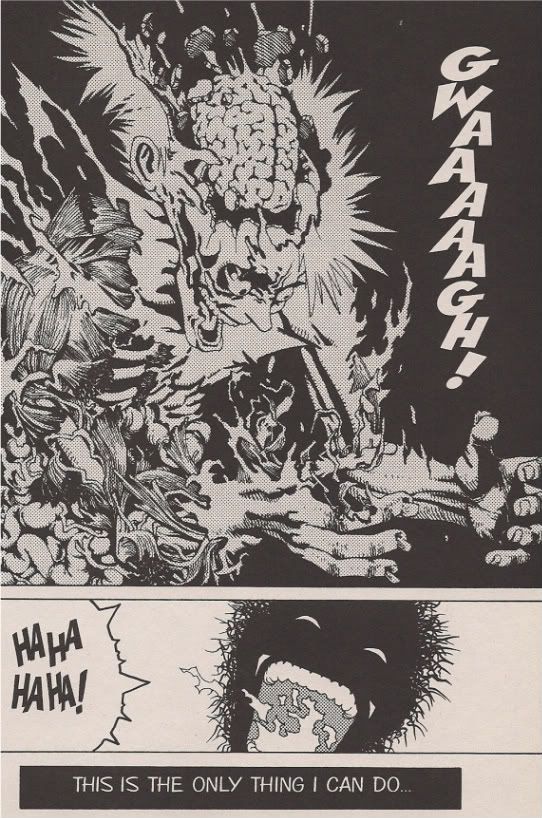

It's ok: Snev kinda likes it too, that weird pleasure of his artificial body falling to pieces; it's the fatalism of these stories literalized into an in-action motive. His teammates hate how he cheapens the sport with such circus hi-jinx, even though the best of them, Dolagunov (the semi-Marv design, here a villain) is doped to shit on designer sensory boost Accel, which a pharmaceutical corporation is trying to promote via racing victory. Granted, Snev used to believe in victory too, until the urge to self-destruct rose in his very first pro match, when some guy ran onto the track, and Snev was too far into winning velocity to move away, and:

I think that was a deleted scene from A Game of You.

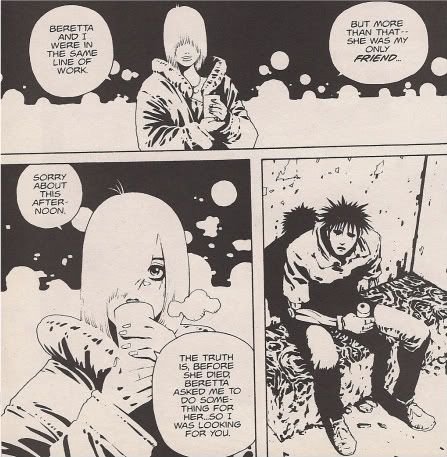

Anyway, Snev is also good friends with Beretta, one of the city's various angelic-yet tough prostitutes (oh yes), who winds up getting him into a heap of trouble when she swipes a Very Important Briefcase off of Snev's team manager, resulting in her murder and a violent race to discover the dirty secrets behind tomorrow's sports entertainment. And a scene in which a dude who looks like a boyish manga version of Dream of the Endless punches a cyborg until his brain squirts out the back of his head. Comics!

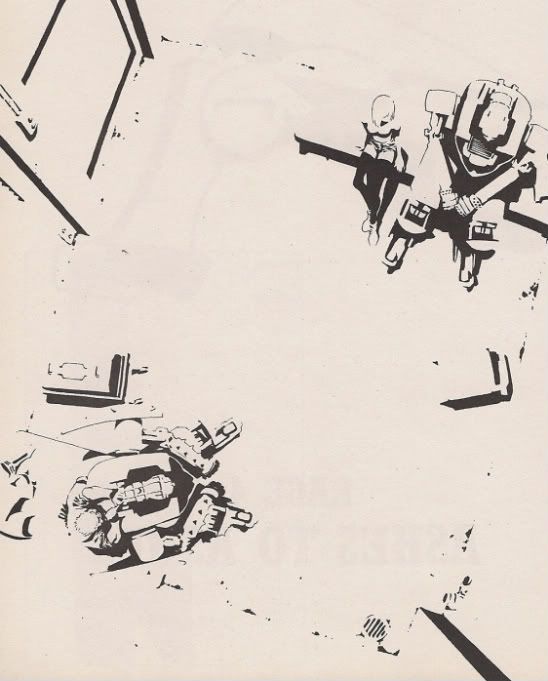

It's a fast-paced thing, probably not as tightly plotted as it could be, but consistently diverting. The real fun, though, is seeing Kishiro cook up increasingly showy visual tricks, balancing the obvious Miller influence with alternate approaches. You'll note, for instance, that all of the book's female characters are drawn in a more classically big-eyed style; this becomes a means of asserting their otherworldly beauty in the city without pity; talk about on a pedestal.

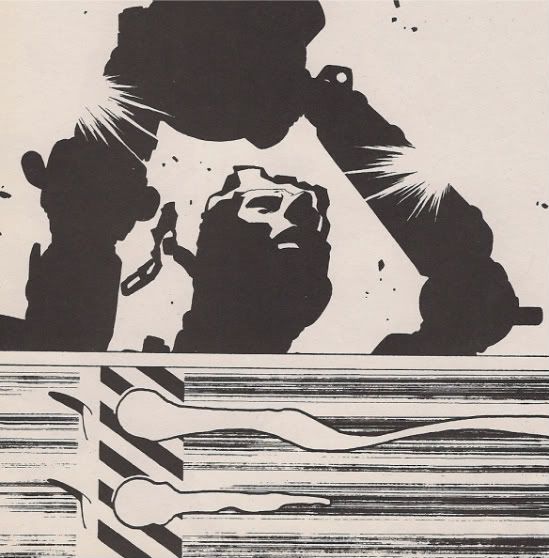

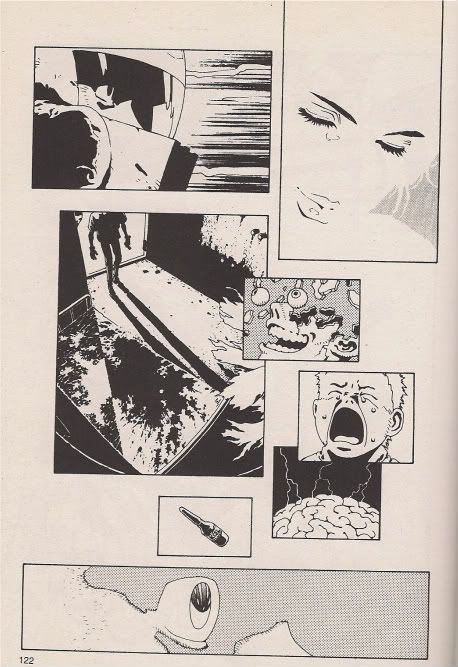

Other moments see the artist break his pages apart, glorying in the arrangement of panels for purely emotional effect.

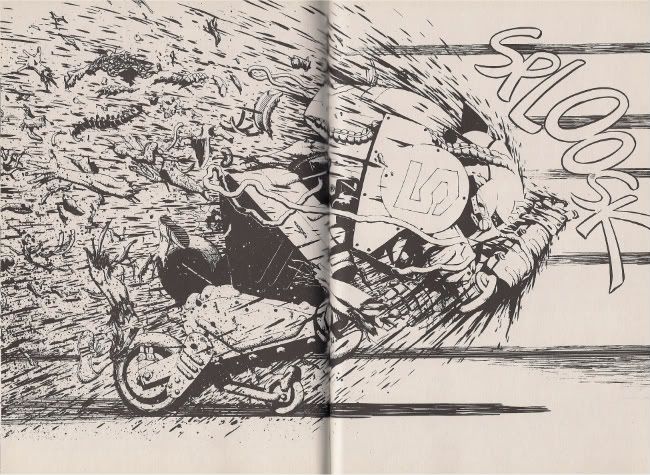

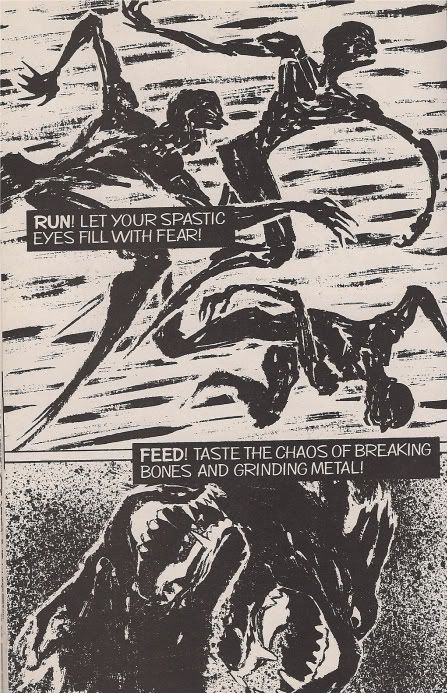

And occasionally the art simply erupts into slashes of pain, obliterating fixed representation entirely in favor of the sensation of Snev's total immersion in the ecstasy of racing.

It all comes down to a final showdown on the track, naturally, where Our Hero must either live up to his self-made expectations or ruin everything that makes him a viable talent by succeeding for once; more complex than the average Sin City yarn, probably, but appropriate for a book in which an artist fresh off a big, successful series wanders around some striking, hopefully personally satisfying territory at some risk of alienating readers. He's made it his own.

You can probably see it for yourself, even if VIZ isn't keeping it in print. Online used bookstores tend to reward searches for lost manga nuggets like this one, and the rewards won't stop with finding a $1.30 library copy. This is eager, restless stuff, international yet so much of its birthplace. The kind of manga publishers used to hope for, an East-West 'bridge' to ease readers in. Those aren't common anymore; in time, you can't win for losing.