Old English #1

/![]() Perramus: Escape From the Past #1-2 (of 4)

Perramus: Escape From the Past #1-2 (of 4)

Q: God, what the hell am I going to do with all these old foreign comics I bought in that April research binge? That was addressed to you, God.

A: This is a new series of short posts about old English translations of foreign language comics, probably still obtainable through back-issue and/or used book resources. There will be lots of pictures, as per God's advice.

And we might as well start with a veritable legend of sinking into oblivion, Fantagraphics' late '80s/early '90s magazine-sized pamphlet translations of Euro-by-way-of-South-Americomics. The publisher's five-issue, 1987-90 take on Carlos Sampayo's & José Muñoz's Sinner is probably the most prominent of the bunch, but there was a later, odder release in the same format: Perramus: Escape From the Past, a four-issue, 1991-92 release of work by writer Juan Sasturain and artist Alberto Breccia.

It was a curious release, not least of all for being a formidable bait-and-switch; all cover-sourced close-up skull imagery and "the horror is real" and POLITICAL HORROR CLASSIC notwithstanding, Perramus actually isn't a horror comic by most standards. There's horrific sequences, in which the art gleefully trades in terror comic visual tropes, but this is mainly in the service of genre-comprehensive allegorical adventure serial, prone to marshaling all manner of cultural stimuli in the service of confronting recent, awful political history.

Perramus was first published in 1984, serialized in the Italian anthology series Orient Express. Its first collected edition appeared in Europe in 1985, and subsequent editions continued along until 1991. It's a four-volume series, although most European editions compile vols. 1-2 in a single album, resulting in three books. Fantagraphics' four-issue English-language release, despite kicking off the year the work was completed, does not correspond to the four volumes of the original work; rather, every two or so issues collects one volume, which means the series halted around the end of vol. 2 (or, the first of the common European albums). I'm equivocating since I only have the first two issues, which definitely cover the first original volume, since they end on an Epilogue at a natural stopping point.

But maybe it's fitting that such a work stretches across so many odd, international forms; perhaps it could only really be at home in Argentina. Breccia (who died in 1993) was a giant of Argentine comics, who specialized in fantastical horror comics of a more traditional sort. Indeed, English edition editor Robert Boyd suggests in a much-needed back-of-issue #1 biographical essay that Breccia gradually moved deeper (if never completely) into a literary horror emphasis -- Poe, Lovecraft adaptations -- as a means of evading the hazards of Argentina's increasingly brutal political situation in the 1970s. His frequent writer, Héctor Germán Oesterheld, "disappeared" in 1976 as the duo prepared a comics biography of Che Guevara; is there any more appropriate response than horror?

Argentina's military junta relinquished power in 1983, and Perramus began almost immediately thereafter from a script by Sasturain, a novelist and poet. The story begins with an unnamed man fleeing the dead-of-night approach by a (literally) skull-faced death squad, dooming his revolutionary compatriots left behind, still asleep. In a daze, the man wanders into a teeming nightclub where he's offered his choice of three prostitutes: Rosa, for luck; Maria, for pleasure; or Margarita, for forgetting.

The man opts for Margarita, and surely does awake a while later without the slightest idea of who he is, or what he's done. Dressed in a patchwork uniform left from johns of many nations, he derives his identity from what's closest to his heart.

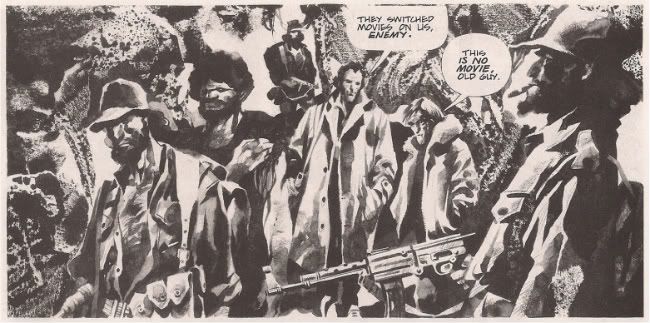

What follows is a freewheeling series of events, chopped up into 2000 AD-sized chapters, seeing Perramus and a growing band of companions through various satirical encounters. Conscripted by the death squads to body-dumping detail aboard a ship, Our Man and one Washington Sosa -- possibly an allusion to a sidekick character from one of Breccia's earliest adventure comics -- escape to an island where a local dictator justifies his existence with an annual trotting out of society's Enemy (a downed foreign airman), who's recently begun a campaign of civil disobedience by refusing to escape.

Then there's a run-in with an equally dictatorial film company that only makes trailers, although their enforcers are fortunately well-trained enough to fall down and play dead when you pretend to shoot at them. Less playful are Perramus' old cohorts at the Volunteer Vanguard for Victory -- not the ones he got killed, mind you -- who don't recognize him personally but do understand the revolutionary potential he carries. History seems to be repeating, along with visions of Margarita, who appears to be somehow present in every escapade in the form of a different woman; and she's not the only one he'll be seeing again.

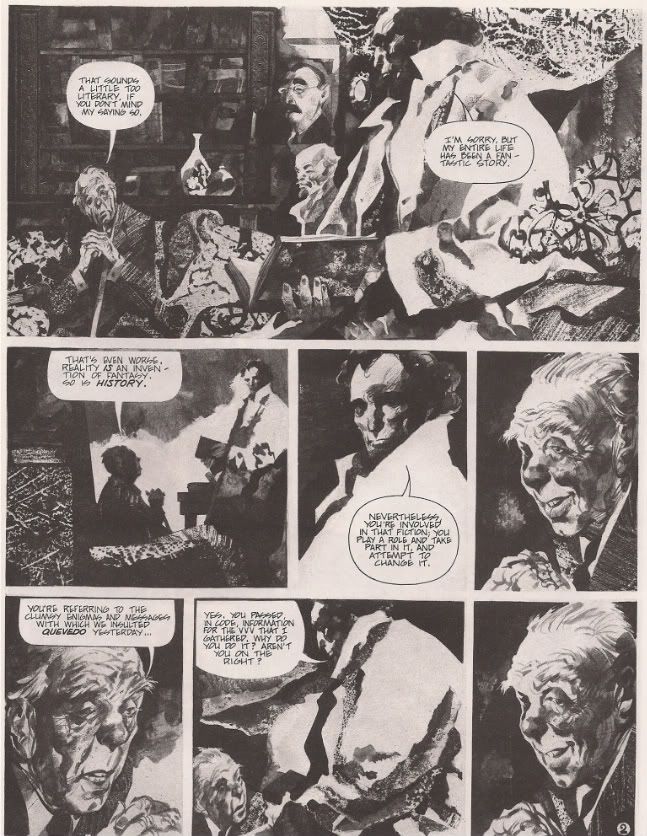

Recurrence is an important theme in this work, along with development. Surely the visuals seem to be redolent with Breccia's own evolution; any given panel seems hell-bent on packing in as many mixed-media flourishes as possible without sabotaging readability, although the sheer richness of these images can nonetheless seem overwhelming. Lavishly caricatured figures share space with environments ranging from suggestive swirls and dashes of ink to photographic collage. Supine corpses are covered with a gauze of light against deep shadow -- respect for the dead -- while death squad skulls hide additional skulls in their hats, symbolizing the authoritative facet of their personal killings. Often the human figures will recede into silhouettes, left small and alone against the mayhem of clashing textures that is Breccia's South America, a world of sufficient unreality arranged to register as nature, and sometimes be beautiful.

Yet persona and politics is fundamentally a construct, as the titular runaway learns late in issue #2 as part of a titanic team-up with Argentine literary lion and in-story secret agent Jorge Luis Borges, ready to encode messages in the poetry of 15th century Spanish satirist Francisco de Quevedo (and still alive at the time of the material's early publication). Sasturain & Breccia make mention of Borges' 1942 story Funes the Memorious as a sort of mirror to their own story; Funes also met Borges, but his talent was to remember everything, to the point where his command of detail undercut his capacity for abstract thought. In contrast, Perramus meets Borges unable to recall a thing about his past life, which renders him sheer abstraction, fortuitously wandering a continent of abstracted political and societal ideas, fastidiously rendered by Breccia in multimedia splendor.

Does it go deeper? Down to the literary Funes' Uruguayan heritage, same as Breccia's?

Ah, but even Borges himself is part of the plan, recontextualized like a good frequent literary character into an avatar for sheer artistic skepticism. In this world, the real Borges' politics needn't matter so much as his art's capacity for inspiration. This mixes well with Breccia's self-reference, his horror images positioned in society now explicitly in the form of repression, rather than as a response to such. There's plenty more where that came from - I sincerely doubt you can grasp the totality of this work without a serious command of Argentinian politics and culture, which I don't have. Still, as the might of Breccia's art is obvious, so is the broadest contours of his and Sasturain's story, looping Perramus back to the mystic nightclub for the volume's end, where the prostitute again offers what's expected: his desire. Will he have learned for next time? Will his country?

There's a little bit of an answer in these two Fantagraphics issues I have, and obviously more in the other two, although the other half remains obscure. I can't imagine a comic of this sort did gangbuster business in the US in '91, to the point where I'm mildly surprised that the issues we've got exist. Maybe the future holds something more for Breccia, but until then it's another story from another longbox, undeniably out there.