Hibbs on David Harper's Off Panel podcast!

/Check out my dulcet tones as David and I discuss the current state of the industry. -B

Check out my dulcet tones as David and I discuss the current state of the industry. -B

Follow this link to Mark Evanier's site and watch this video of the Mike Douglas show and see video of DM founder Phil Seuling discussing comics on national TV in 1977. Astounding footage! I never had the pleasure of meeting Seuling, or, prior to this ever even seeing video of him -- so this was a fabulous and fantastic find for me. Thanks Mark!!

I especially like how they're just taking the old comics and flapping them around -- "Oh, look, a FAMOUS FUNNIES #1; here, catch!"

Without that guy you almost certainly wouldn't be reading blogs about comic books today... except maybe in the most nostalgic way.

-B

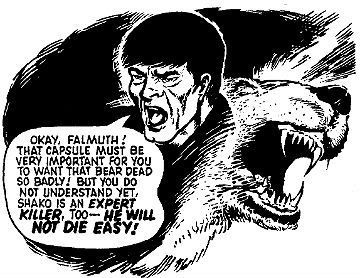

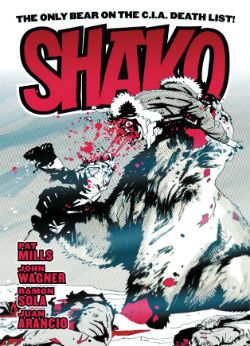

Rejoice fans of quality reviews! For to celebrate the release of the SHAKO! TPB collection I decided not to review it. For a start I won't have any money until Christmas is over. And I'm talking there about the first Christmas after MiracleBoy leaves home in about 2025. No, I decided to do something else instead to celebrate this momentous occasion. What follows is not entirely sane but then again what is, my American friends, what is?!?

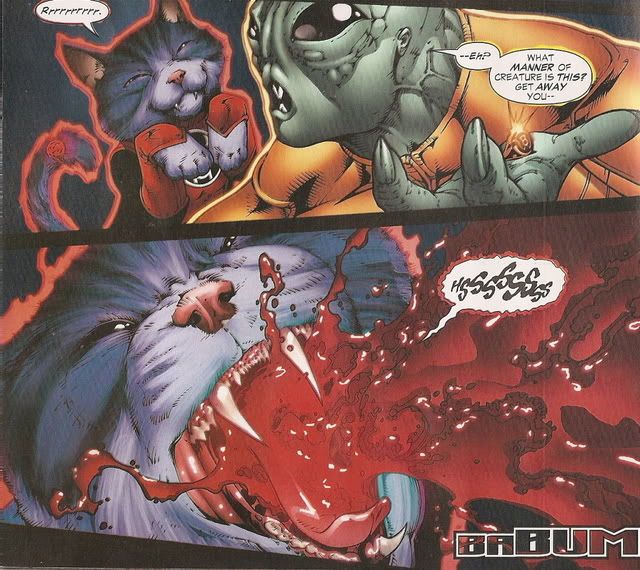

Most importantly of course I decided not to review the SHAKO! TPB as I already reviewed its contents HERE. You will of course remember that vividly because you have nothing else to do but remember badly written old posts on The Savage Critics. So, there didn't seem much point in going over it again but it also seemed a bit shoddy to let the occasion pass uncommemorated. Because as much as I love 2000AD's SHAKO! (and, boy, do I love SHAKO!) I never thought it would be collected. Truly, these are the days.

Your luck was in though as since I am a Savage Critic I, naturally, know loads of people in Comics, or as we gifted insiders call it - The Biz. And using my "juice" I reached out and managed to get the contact details for the star of the book, SHAKO! himself. SHAKO! has kept a low profile since his 2000AD appearance moving into the area of plumbing due to the "perennial" nature of the work and the reliable income it provides for a family oriented bear like SHAKO!. SHAKO! still retains fond memories of his comics work and remained humble and gracious throughout our encounter. Because encounter SHAKO! I did. In fact, as his van was in the garage, I arranged to meet him around the corner from his house at a caff where we both tucked into a full English courtesy of The Savage Critics’ robust expense account. The following conversation ensued:

JK: SHAKO!’s quite an unusual name for a bear isn't it? SHAKO!: No, not really. Although in the strip it claims “It means simply...KILLER!” or some other such guff. But I'll let you in on a little secret - it’s actually Inuit for Grace Of The Sun’s Soft Fade. Sorry to disillusion everyone there.

JK: Ha! I can see why Mills' went for "...KILLER!" That's more in line with the spirit of the strip. Were you ever bothered by the levels of violence? I mean the audience for this was largely children after all...

SHAKO!: No, no. You can't mollycoddle children. The world is full of things children shouldn't be exposed to but they have a quite unerring radar when it comes to locating them. I mean, sure, it was over the top but it could have been worse. Look, it isn't complicated; do you know the only sure way to stop your kids from finding your jazz mags in the airing cupboard?

JK: Er, no.

SHAKO!: Don't have any jazz mags in your airing cupboard.

JK: Er.

SHAKO!: C'mon, who's going to tell the world it can't have its jazz mags? It just doesn't work like that! So inoculating the little blighters was, I guess, the intention behind all that newsprint nastiness. Of course by jazz mags I mean violence. I'm sorry, I had a late call out last night to bleed a pensioner's radiators. I 'm still a bit tired, not as young as I was y'know. I'm no Spring bear! Could we keep it lighter maybe?

JK: Sure. Sure. You were kidding a bit back there weren't you?

SHAKO!: Yeah, heh. Polar bears love deadpan, what can I say?

JK: I thought so, it's just hard to tell with the snout and the fur and all that.

SHAKO!: That does help with the deadpan. Still, I mean the violence in my strip was nothing compared to that in HOOK JAW. That was like, well, I don't know what that was like! It was off the scale. I'm amazed no one ended up in prison over it. He had a real knack for the violence, I'll give him that. And in real life he was such a sweetie!

JK: You mean Pat Mills?

SHAKO!: I meant Hook Jaw actually but I suppose the same might be said for Pat Mills, yes.

JK: You worked together quite recently didn't you? You and Hook Jaw?

SHAKO!: That’s right! We did indeed. It was just a bit of fluff really, stunt casting overseas under nom de plumes. A bit like when Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing would turn up in some Italian fiasco no-one in England would see for decades. Seabear and Grizzlyshark? I don’t think many people saw it but when you get to our age that’s not so important. Your priorities change as you age and it actually gets to the point where it’s just nice to be asked. I mean at my age my cubs have got cubs of their own so they're too busy to bother with boring old me! Something like Seabear? That's just the ticket, you know? A bit of a lark. Peps the old bones up a bit. Hardly high art, of course, but it was nice to stretch the acting chops again and, of course, Hooky was a riot. No airs or graces with that one! Ho! We kept in touch afterwards. Right up until…

(Legal Note: SEABEAR & GRIZZLY SHARK are nothing to do with HOOK JAW or SHAKO! Nor did the creators intend any such inferences to be made. The shark doesn't even have a hook in its jaw. I am just having a spot of fun. Is that still legal? EH!?!)

(Legal Note: SEABEAR & GRIZZLY SHARK are nothing to do with HOOK JAW or SHAKO! Nor did the creators intend any such inferences to be made. The shark doesn't even have a hook in its jaw. I am just having a spot of fun. Is that still legal? EH!?!)

JK: Yes, I heard you were there when he…went.

SHAKO!: I…yes..it…sorry…

JK: It’s alright, we can move on if you like.

SHAKO!: No…no. I think Hooky would want people to know he was at peace at the end. In fact his spirits were quite high if anything. You know they’d just started reprinting his work in STRIP? People were recognising him again. Staff and kids from the other wards would go see him in the Day Room and ask for his autographs. Oh, he was fair basking in it. It was nice timing as well because a couple of days later…he...it was...

JK: It’s okay. I know this must be difficult for you...

SHAKO!: Yes..but, no, actually in a strange way it was kind of comforting. I’m not really sure what happened to tell the truth. It was Tuesday visiting and I was sat next to his bed and I remember I was telling him about this little cameo I’d made in one of those terrible Event things. One of those art by committee things. Dreadful tat but awfully popular with the youngsters. There were like five writers or something ,and they still got which Pole we bears live at totally arse about tit. Bless his cotton socks, Hooky was trying not to laugh because of the pain; the drugs weren't really touching it by this point. And suddenly, suddenly I realise there’s a man in the room. Seems daft but at first I thought it was a bear. Big fellow he was. And hairy? I’ll say he was hairy, alright! It was his eyes though, his eyes that held you. Great sad things they were. Sad but dignified. Like he’d been hated by the world and forgiven it. And this chap, he puts his hand on Hooky’s dorsal, and it’s a big hand festooned with these big rings, and he puts this big hand on Hooky like a feather landing. And all the tension in Hooky’s body just goes and this fellow says, in this burr, this rumble, he says, and I can remember every word still, he says:

“S’alright, Hooky. S’all alright, now. C’mon, me Duck, time to go home. Time to go back where the stories live. It’s just going home, luv. They've all missed you, Hooky. C’mon, son. C’mon now. Gently Bently and off home we go.”

And when he lifted his big ringed hand, well, I could tell from how he was laid that Hooky was gone. Well, I mean, obviously he was still there but…

JK: I understand. It sounds very…odd. It sounds like a very…I guess quite a spiritual moment.

SHAKO!: Oh, it was. Of course then I look and this big hairy fellow’s only gone and put shoe polish on his face and now he's chasing nurses down the corridor while making farting noises with his lips.

JK: …!

SHAKO!: Yes, it did take the shine off of things a bit.

JK: Well, er, that sounds like a good place to finish. I thank you for your time and I wish the book every success.

SHAKO!: Oh no, thank you. And I just have to say it’s not about success it’s just...when you're young it's all about the future isn't it? But then you get on a bit and you realise you aren't going to be in the future but you want to have done your bit.

JK: Entertained people?

SHAKO!: Yes. Yes! Maybe more but that'll do. That's no small thing. It's a bit of a magical thing even.

JK: The magic of stories.

SHAKO!: Yes. The lovely, lovely stories. Y'know, for the young.

JK: Thank you, SHAKO! ________________________________________________________

Postscript: Two days later I rang SHAKO! to see if he wanted to give the transcript a once over. The phone was answered by a man who said only “Shako’s with the stories now, luv.” Before the receiver was replaced softly.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

This one was for SHAKO! and all the stories, and all the kids that read them.

This one was for all of the COMICS!!!

WOLVES AND MOOSE! THE RATTLESNAKE AND THE MONGOOSE! COMIC CREATORS AND COMIC CRITICS! NATURAL ENEMIES ENGAGED IN A TERRIFYING DANCE OF DEATH. BUT UNLIKE THE LAMBADA, THIS DANCE IS NOT FORBIDDEN, FOR THIS DANCE IS CALLED...

In the CREATOR corner, hailing from the mean streets of Hollywood, California– Mark Sable… author of GROUNDED, HAZED, TWO FACE YEAR ONE, CYBORG,TEEN TITANS: COLD CASE, WHAT IF SPIDER-MAN OH WAIT ALL THE JOKES ABHAY CAN THINK OF SEEM KIND OF RACIST NOW, FEARLESS, RIFT RAIDERS, and/or his latest book from Image Comics, GRAVEYARD OF EMPIRES with Paul Azaceta (POTTER'S FIELD, SHI: SHOWDOWN IN BONERTOWN).

In the CRITIC corner, Abhay, author of such controversial internet facebook status updates as "Iron Man Is Talking All Weird in FEAR ITSELF", "Dark Knight Returns: Dude, Have You Heard Of This Comic?", and "Oh shit, Charles Schulz Forgot to Ever Let Charlie Brown Kick the Football."

Author: Mat Brinkman, drawn in 2000-2005, first published in Paper Rodeo, Monster 2000, and The College Hill Journal, collection published by Picturebox, Inc., with cover design by Ben Jones.

BUT FIRST… OUR DISCLAIMER FROM MARK SABLE: As a working creator, it’s hard for me to comment critically on comics. It’s a small industry, and creators can be a bit sensitive. I don’t exclude myself from that category. Nor do I think I can do better than anyone associated with this book or any other we might comment on. I say that not because I want you to feel bad for me. This is just a way of apologizing to creators/editors/publishers in advance to save my own ass. And to a lesser extent apologize to your readers if I hold back. The point of this, from my end, is to see if a creator can speak critically about comics in the mainstream while working in the mainstream. That, and to plug the shit out of my work.

PLUG DEPARTMENT: Two issues of GRAVEYARD OF EMPIRES are in comic stores now. Also, in the Previews catalog this month, collected editions of FEARLESSby Mark Sable, David Roth & PJ Holden (Diamond Order Code SEP110399), published by Image Comics, and DECOY by Mark Sable & Andrew Macdonald, M.D. (Diamond Order Code SEP111131), published by Kickstart Comics.

* * *

ABHAY: So, in our last little tete-a-tete, you said something like "When I started with Paul…his work and his ballsack were both an acquired taste for me. I grew up thinking the ultra-detailed work of Jim Lee and Marc Silvestri occupied a higher place on the evolutionary scale. I’ve gained a respect for fundamentals and for a less-is-more approach and just for ballsacks generally." That's pretty much an exact quote. Also, since we last spoke you've gone to China on a Young Alumni trip, by pretending to be a "young person." So, as Marc Silvestri Super-fan #1, what do you think of the art in MULTIFORCE? Do you like it for sophisticated "I am a fancy, fancy professional comic writer" reasons? Do you enjoy Mat Brinkman's drawings on a pure "Ooooh, monsters level"? Or do you hate it? Do you just fucking hate it and looked at MULTIFORCE through gritted teeth the entire time? Have you perhaps been brainwashed to want to assassinate Mat Brinkman by the Chinese? Are you the Manchurian Dork?

ABHAY: So, in our last little tete-a-tete, you said something like "When I started with Paul…his work and his ballsack were both an acquired taste for me. I grew up thinking the ultra-detailed work of Jim Lee and Marc Silvestri occupied a higher place on the evolutionary scale. I’ve gained a respect for fundamentals and for a less-is-more approach and just for ballsacks generally." That's pretty much an exact quote. Also, since we last spoke you've gone to China on a Young Alumni trip, by pretending to be a "young person." So, as Marc Silvestri Super-fan #1, what do you think of the art in MULTIFORCE? Do you like it for sophisticated "I am a fancy, fancy professional comic writer" reasons? Do you enjoy Mat Brinkman's drawings on a pure "Ooooh, monsters level"? Or do you hate it? Do you just fucking hate it and looked at MULTIFORCE through gritted teeth the entire time? Have you perhaps been brainwashed to want to assassinate Mat Brinkman by the Chinese? Are you the Manchurian Dork?

MARK: China...I'm still trying to come to grips with everything I experienced there. It's hard to say things that aren't cliche. The scale and pace of growth are astounding. You can literally see the place growing; there's more cranes in Shanghai than in all of North America, or so I was told. There is a frightening uniformity of thought. You get pretty much the same answer to even marginally political questions from everyone. But they're much closer to history - 100 years ago they had an Emperor, the Communist Revolution is a little more than 60 years old. Most people seem to be so thrilled to be eating, let alone have the kind of prosperity we're enjoying in The West, that whether they can't get Google or Facebook is not high on their priority list. I hope I'm wrong, but I don't think there is going to be a Chinese version of an Arab Spring there anytime soon.

Since the last of these, I also started life drawing so I could communicate with my artists better, to try to make up for some of the visual arts background that almost every other creator has. I could devote my life to it and never approach the level of a professional artist, but learning to draw has deepened my already deep admiration for what it is artists do. My estimation of Paul Azaceta has grown and grown. It wasn’t that long ago that Paul was only viewed as someone who could do “dark and edgy” books like Daredevil or Hellboy. Putting Paul on Spider-Man was a brave choice on the part of Steve Wacker (someone who does not get enough credit for the eclectic talent he's brought to the forefront of Marvel, like Marcos Martin, Max Fiumara, or Paolo Rivera). And for whatever the flaws in the writing of HAZED, I couldn't think of a better tone for it than the cartoonish take Robbi Rodriguez brought. I got lucky that Robbi (who’s now been snatched up to draw Uncanny X-Force, so score another one for Marvel) sensed that style would help lighten what's actually a pretty dark book.

When I look at Brinkman's art, I definitely have an appreciation for it that goes beyond the "ooh monsters level" (although that's there too). I'm blown away by the detail and scope of the book. It benefits from being oversized.

Intent is something that matters a lot to me. That's something that turned me off about a lot of critical theory when I was in college, this idea that intent doesn't matter, all that matters is the viewer's subjective experience. As a creator the idea that intent doesn't matter makes me feel pretty fucking useless. If I thought this was the ONLY way that Brinkman could draw little wizard people and giants, if I thought this was his attempt at drawing them realistically and this is what came out...honestly, I wouldn't respect the work asmuch. Clearly, he made a choice to draw in the style that he did, and to me that choice is what makes something art.

ABHAY: ...I disagree. (I'm apparently on the side of the education system that tried to no avail to teach you). I don't think intent matters at all. I just don't think anyone can be good enough to consciously control what something "means" for everybody that sees it, and the idea that anyone has a right to tell people that their interpretations are "wrong," even the work's creator-- I think it's kinda morally repugnant for anyone to claim to have that power. It transforms a conversation into a lecture, and if people liked lectures... If people liked lectures, we'd all still be watching STUDIO 60 ON THE SUNSET STRIP. That Aaron Sorkin idea of forcing the audience to agree with you on how to feel about the work, that lame lecture he gave telling people how to feel about the phony women he made up in the SOCIAL NETWORK-- I find that to be a more unpleasant thing about the guy than the crack cocaine abuse...? "I prefer that he be a crackhead." <=== There's a sentence I've always wanted to type.

Whether or not someone made a "choice" is just a locked-room mystery. Say that Mat Brinkman were assassinated by you tomorrow, on instructions from your Chinese overlords, and you were to burn everything he ever did but MULTIFORCE. There would be no way for future generations to definitively know if Brinkman made a choice or not. By your reasoning, would it still be art?

MARK: You could not be more wrong. I mean, I get where you are coming from. It’s insulting as a reader, and I imagine a critic, when anyone tells you how to think. But that’s not what I’m suggesting at all. You’ve created a false narrative where all artists want to impose their vision on everyone. Yes, we all want to be loved by everyone, but it takes a kind of ego I’ve yet to encounter to think that you can control everyone’s opinion. Sorkin is a total straw man-- I’ve been around too many artists to think that’s how most of us think, and so have you.

I’m sure some creators feel that they are the ultimate authority on their work and that what the reader thinks doesn’t matter. But to a certain extent you have to feel that way. If you take every note or criticism as equally valid as your own, if you try to please everyone, you’ll please no one. And I think most of us do care what an audience thinks and that reaction is important to us-- not so much in the sense of whether you like what we say, but whether we doing our job, to effectively communicate our story and get you as a reader to care about it.

If it’s “morally repugnant” for a creator to dictate how someone should feel – although it’s our job as creators to MAKE audiences feel – it’s even more repugnant to say that the creator’s intent means NOTHING. The logical extension of the argument is that every reader’s opinion is equally valid. There’s a difference between an essay and play, or a blog post and a graphic novel. That difference stems from the intent of the creator, from a conscious choice to create entertainment rather than to lecture.

A critic can’t hide behind the notion the locked-door mystery notion of never having a perfect understanding of the artist’s mind. You’ve got to at least attempt to grapple with intent to give a full appraisal of the work. On the flip side, a creator can’t hide behind the impossibility of trying to communicate the exact same idea to everyone, otherwise they wouldn’t try to communicate with ANYONE. The negation of criticism is morally repugnant because it stifles open discussion of art. But the negation of creator intent is similarly repugnant because it stifles the CREATION of art. Why bother creating something if your intent doesn’t matter?

Let me ask... with your own stuff - how much is drawing it yourself a desire to control or own the process of creating a comic? And to bring it back to what I was saying about Brinkman, how much of what we see on the page looks that way because you happen to draw that way, or because you can ONLY draw that way? Versus you making a specific stylistic choice, like using the clip-art style for Dracula? And the big over-arching question - do you think YOUR intent matters?

ABHAY: This is Creator vs. Critic, not Creator vs. Wildly Less Accomplished Creator. You've broken the entire premise of these interviews, in question one.... For me- drawing my own webcomics has always been the only choice, but no, none of my "art" is "intentional." I draw like shit quite involuntarily. I want to be simpler; I want to be faster; I want to draw hands that look like human hands instead of deformed bird claws. But I'm not making any money with webcomics, or even aiming to, so I can't afford to pay an artist, or to waste one's time. I can barely justify the amount of time it takes ME-- let alone doing that to another human being...? But that's fine-- I'm very happy with the road I'm on. I get to make hard R-rated comedies, and even if I had any talent, I don't think there's any road in "professional comics" that would let me make my comics. And I know from seeing what other people's destinations have turned out to be, that I surely don't want their resumes for myself. I mean, not if the best case scenario for being a writer in comics is having your name associated with UNCANNY X-MEN getting cancelled in UNCANNY X-MEN: THE CROSSOVER so that Marvel can launch a brand new book called UNCANNY X-MEN. Yikes. I would prefer that you all be crackheads.

MARK: I think you are using your limited palette of choices to try and deny that the choices you do make matter. That’s some more bullshit right there. Every artist has limited choices. And just as you’ve created a straw man with Aaron Sorkin, you’ve created this false dichotomy where there are only two kinds of creators. You can either be this handicapped martyr who is forced to draw people with claws because he’s mean to other creators, or a sellout who abandons their artistic integrity to write a renumbered superhero franchise book. I have to believe as a creator I can do both, or find work that lies somewhere in between those extremes.

And in that false dichotomy, you’ve also proven that you DO care what the author’s intent is. You clearly look down on the choice to write the Somewhat New, Slightly Different X-Men versus creating things your way (or Mat Brinkman’s way). It’s fine to hold that opinion, but don’t pretend that what the author is trying to do is not something you care about. Or that it’s not something you take into consideration when you evaluate their work.

Put that in your crack pipe and smoke it.

ABHAY: Let's just get some background. What's your experience with art comics generally? Have you read any Gary Panter? Have you ever looked at a MOME or KRAMER'S ERGOT? Is that a sector of comics on your radar? Honestly-- art-comics are not an area of comics I feel especially confident about. I've read my share but I always feel very badly under-read when it comes to this area of comics. I'm sure anyone reading this who's more knowledgeable about that world is going to be unkind about how shallow my questions are, which is fine; I can't blame them. So, this interview is going to be the blind leading the blind. This interview will be like hearing about sex in middle school, back before the internet existed when junior high kids would talk about sex but not know what they were talking about, not have seen 500 hours off Redtube. I remember once over-hearing two kids in my middle school talking about an erotic dream one had-- this is 6th grade, maybe. The part that has stuck with me decades later was one of my classmates saying something about "me and her started spraying one another with deodorant." Which... deodorant? To this day, I wonder, like-- was actual sex disappointing to him, when he discovered that deodorant sprays would not be a part of the experience of losing his virginity? Or .. or am I doing it wrong, Mark? Should there be a part where I spray deodorant? ... Explain sex to me, Mark Sable.

MARK: Fuck that. I want you to explain sex to me, Abhay. I’m not even kidding. We’ve known each other for years and while I think you could probably name every one of my ex-girlfriends, I know next to nothing about your personal life. Mostly because I’ve been afraid to ask. But no more! Just as part of my goal is to get you to do more creative writing in addition to your criticism, I’d love to break you down and get you past absurdist writing and get you to delve into personal stuff. I’d love to see if there’s a “Paying For It” in you.

ABHAY: ...I don't actually know any of your ex-girlfriends, Mark-- I met one of them at a birthday party back, maybe, five years ago now...? Annnnd that's it(?). But yes, I am working on a sequel to PAYING FOR IT. The title's going to be APOLOGIZING FOR IT. It's just a one panel strip of me saying things like "don't take it personal-- I'm under a lot of stress" or "God, do you need so much attention? I'm trying to write about comic books over here." It's going to be pretty terrible, worthless and unlovable-- like MARMADUKE, basically. That's basically how I introduce myself to women now-- "Hello. I am a Sexual Marmaduke."

MARK: You’ve met at least one or two of my ex-girlfriends. You had dinner with the anti-Semitic one. And I mention “Paying For It” because that’s maybe the last “art” comic I read. I haven’t read Kramer’s Ergot but I’ve read Poor Sailor. I love Adrian Tomine and Chris Ware but…are any of the comics I’ve cited “art comics”? That’s how uninformed I am – I’m not even capable of formulating a definition of what an art comic is, except perhaps in opposition to superhero comics.

Something that’s frustrating to me is that it seems there’s mainstream superhero comics on the one hand, and there’s the APE/MOCCA DIY stuff on the other. I don’t know that I feel particularly welcome or at home in either community. I mean, my last books few creator-owned books have covered war/horror (GRAVEYARD OF EMPIRES), espionage/high concept techno-thrillers (UNTHINKABLE) all-ages time travel (RIFT RAIDERS) and a satirical take on sororities and eating disorders (HAZED). They aren’t superhero comics, but I wouldn’t necessarily call them art comics. How would you categorize them?

ABHAY: You know how on the Dukes of Hazzard, there'd be those shot of a car about to crash into some hillbilly barn, how it'd freeze and Uncle Jesse would come on and say something like, "Old Boss Hogg surely didn't realize the trouble he was getting himself into this time." I just experienced my own personal version of that.

MARK: ... What disqualifies them as art? Do they fit too neatly into genres? Are they too high concept? Does it have something to do with my intent? To some extent, I don’t care, but the reality is I have to market these books to an audience and market myself to artists, editors, publishers etc. So these distinctions do matter. What is an art comic?

ABHAY: Discussions of definitions are always just the most pointless conversations on any comic part of the internet. Scott McCloud came up with a definition of comics that excluded Family Circus or the Far Side somehow. The Comics Journal had a definition that included Al Hirschfeld illustrations somehow. At one point, wikipedia had a definition of art comics as something like "comics that share their aesthetics with the art world" -- that wikipedia entry was then deleted and destroyed in its entirety by people with their own definition.

MARK: Definitions are imperfect, but it’s hard to have a discussion about something you can’t define. Why is Multiforce an "art comic?" It seems to me what qualifies this as “art” is that it’s not about superheroes and that it’s not aimed at a commercial audience. I get the former when we are talking about Maus, but Multiforce isn’t about the Holocaust, it’s about (to the extent it’s about anything), two little wizard dudes fleeing the destruction of city after city by giants with axes for arms. Don’t get me wrong, I love that…but the knock on superhero comics is that they are juvenile, I don’t see the subject matter here being any less juvenile. You can even argue the art style is juvenile. It evokes the kind of doodles you’d do in school, although there’s an intricacy to it that’s astounding. But it at least appears to lack some things that you’d traditionally associate with great art or literature, like grappling with big ideas of existence or transcendent technique.

ABHAY: I think you're applying the wrong criteria. "Does it transmit great ideas about existence?" might be a helpful question to ask yourself if you're judging Russian novels, but MULTIFORCE is visual art and those questions in that context seem inappropriate. Does a Mark Rothko painting or a Franz Kline painting succeed or fail based on whether or not it transmitted a "big idea of existence" to you when you view it? Arguably not-- so why would you insist that we judge MULTIFORCE by that criteria?

MARK: To talk about comics as if they are simply visual art and not narrative art is to dismiss half the equation (and in most comics, half the creative team). I find it arbitrary that you make the distinction between what’s an art comic and what’s not based on visual and aesthetic considerations as opposed to literary ones. I think that reflects a particular bias on your part about what you want to see from comic creators who possess the freedom to do their own work. It’s completely valid to want those things and judge them from that perspective, as long as you admit it’s just as useful or useless a way of defining things as choice of genre is when evaluating something’s worth.

ABHAY: I don't know... You sound a little offended that no one thinks your high concept techno-thriller comics are art, but... Were they meant to be? Were they meant to be judged on the same terms as MULTIFORCE? Or are they entertainment? There's a distinction between art and entertainment, and however nebulous that distinction is, it's not all that hard to make at least a superficial call. Especially with comics-- you can judge them by the covers. I mean, sure-- anyone who's written anything has thought "wowee zowie-- I'm expressing myself!" And so I guess any distinction I'd draw there-- that MULTIFORCE is plainly operating more in a tradition of self-expression than anyone would expect from an Image comic, with a goal more so to create something unique to the artist, etc... I mean, sure, I can see how a person would take offense to that sort of formulation. How that'd put your back up against a wall, a little. But I'm not saying that entertainment can't ever be art...

MARK: I find the idea of “self-expression” interesting for a couple reasons. One, because I know you keep saying over and over again that you don’t care about the intent of the author. But how can you categorize something as self-expression without knowing and judging what the author’s trying to express? The more I think about it, the less I believe you don’t care about that distinction. I think if you were honest, you would say you prefer and regard more highly comics that push the envelope visually. And you respect those creators who intend to push those boundaries more than those that don’t. Also, “self-expression” can be a juvenile and masturbatory way to approach art. To me it implies a sense of self-importance and a lack of regard for the audience. This idea that everything everyone has something interesting to say. I think Twitter is living proof that’s not true.

With the term art comics, there is a perceived value judgment. Whichever definition you use, it automatically implies anything that doesn’t fit that definition is NOT art. Whether you consider my particular body of work art is not terribly important. But I think it is important that there are creators and, more importantly, readers, who feel excluded from both communities as a result of these arbitrary definitions.

My first reaction to your question here was – why the fuck should you care why I write what I write, if you don’t care about an artist’s intent? I write them to entertain, yes, but also to inform and provoke. And to make money and make people like and respect me and to make myself feel like my life has some worth since I haven’t created any actual people yet (that I know of). And a hundred others things including, yes, to express myself. I give you shit about the artist’s intent mattering more than you think it does. But in thinking about my own intentions in creating comics…there are so many and it’s so hard to pinpoint, especially with the passage of time…I see why it can be a futile attempt for a critic to try and discern it. As a creator I’d like my intent to be respected. But that’s only as long as my intent is being correctly understood.

Again, my first reaction is to say that I wouldn’t call my comics art because I think that would be pretentious. But if I dig deeper, that’s because claiming my work is “art” terrifies me. I’m afraid that if I say hey, I think I’m doing some work that merits attention here, I’m not sure I’d like the scrutiny I would get. I respect the hell out of artists that have the balls to say that about their own work. As long as they can back it up.

ABHAY: So, I knew from the get-go that I wanted to follow talking to you about SECRET AVENGERS with MULTIFORCE. Because my suspicion is that with mainstream comics, my suspicion is that we both have read comics for such a fucking unbearably long time, that we "read" those the same way. Not so much "read" them as just... just inhale them, in a sort of automatic way...? If a mainstream comic lasts me more than a couple minutes, it's because I'm falling asleep reading one. I know I've mentioned specific ones to you that put me to sleep. And when I sleep, I have no dreams. Sometimes I put my hand into a flame, just to see if I can still feel things, Mark, or to test how much I love Richard Nixon.

ABHAY: So, I knew from the get-go that I wanted to follow talking to you about SECRET AVENGERS with MULTIFORCE. Because my suspicion is that with mainstream comics, my suspicion is that we both have read comics for such a fucking unbearably long time, that we "read" those the same way. Not so much "read" them as just... just inhale them, in a sort of automatic way...? If a mainstream comic lasts me more than a couple minutes, it's because I'm falling asleep reading one. I know I've mentioned specific ones to you that put me to sleep. And when I sleep, I have no dreams. Sometimes I put my hand into a flame, just to see if I can still feel things, Mark, or to test how much I love Richard Nixon.

So, even though I'm *terrible* at writing about them, the biggest reason I find art-comics like MULTIFORCE valuable for me is because I usually wind up so confused by what art comic creators are doing content-wise and format-wise that they force me to at least pay attention. I may not understand or fully appreciate everything I'm looking at, but I at least have this experience of becoming very cognizant of how I read comics. There may be "less" for me to read in terms of story-- but I'm somehow invited to read more aggressively and I'm more awake when I read it. (I'm fucking terrible at writing about this shit; I always just wind up muttering about how much fun it is to see "one panel turn into another panel" and then giving up but...)

I wanted to ask you about this because I would guess that you are someone who probably subscribes to the goal of the author being "invisible," that zipless-fuck model of comics where the ideal comic experience is one where you don't think about the creators existing and are subsumed entirely into the fictional reality. I don't think that I do because ... I guess I just grew up obsessed with very present authors, with very noticeable authorial stamps-- Alan Moore, Grant Morrison, Peter Milligan, guys who were not shy about standing out from the pack. I think what marked the British Invasion out and what still makes those comics so vital is that comic authors asserted their presence in a way that American authors might still have a problem with, to this day.

MARK: I read most comics on auto-pilot as well. Where I we may differ in terms of the kind of auto-pilot we fly on is that I’m more focused on the writing and story than the art. Which is odd because I tend to tune out lyrics when I listen to music, and I could stare at paintings for hours on end. I guess that’s my bias viewing comics as a primarily narrative medium; I don’t want to be pulled out of the narrative for any reason, be it art or dialogue, good or bad. I don’t want to be taken out of the story because the writer is trying to show me he can write naturalistic “sounding” dialogue, or the artist is showing off a clever panel arrangement that doesn’t serve the story. The worst for me is – I hate fucking feeling lectured too. Nothing turns me off more than a pretentious quote in a comic. Or didactic dialogue that’s there to show me how smart the writer thinks he or she is. Some of my favorite creators did or do that and I wish they’d just trust their stories more.

At the same time - I still revere the authors you've listed. Was their storytelling so good that I didn’t care about their authorial flourishes? Did my tastes change? Am I turned off now because today’s creators are just not as good? Maybe I'm just jealous-- maybe the more aware of the presence of other creators I am, the more aware I am of their success. One of the nice things about reading Multiforce is that…I don’t feel like I’m in any competition with Matt Brinkman. We are trying to do such different things that I can focus on the work.

There’s still some degree of auto-pilot going on. When there are threads of narrative I do find myself trying to surrender to it. I find pleasure in that, just as I find pleasure in just staring at some of the intricately constructed cityscapes or for a good joke. The frustrating thing is, not having any context for this book whatsoever, I don’t know exactly what I’m supposed to be looking for. I feel like I may be missing something Brinkman is trying to do.

ABHAY: I read this essay the other day by Patton Oswalt. It was in his book which... I don't honestly know if I can recommend his book as a whole, but the title essay, Zombie Spaceship Wasteland, I quite enjoyed. The essay breaks down different kinds of genre entertainment-- post-apocalyptic wasteland stories, zombie stories, spaceship stories-- and talks about what the teenage audience for those is like, how what they're into as teenagers predicts their lives to some extent, what happens when they return to those stories as adults. He has these examples, how the Matrix is a wasteland stories crossed with a spaceship story; Star Wars is a spaceship story crossed with a zombie story, etc. He sort of tracks how all popular geek things come from those three adolescent story-types. I'm not doing it justice but...

Or like, I'd heard a podcast. I'm jumping around, but around the same time as I read this essay, I heard this podcast-- it was a panel discussion between Sam Hiti, Paul Pope and Brandon Graham. All three are obviously just heavyweight comic dudes-- I love all of their work. And in this panel discussion, all three of them were extremely dedicated about their work, all of them were talking about the artistry that goes into comics quite eloquently, and it was a great time. But when the topic of subject matter came up, each of them in turn kept mentioning "Well, I was into such-and-such when I was a teenager." None of them thought anything of it-- they just kept saying it in a very unquestioning way, without any ability to hear themselves reference their interests as teenagers over and over. They were all very serious about their work but none of them questioned that their work was just rooted in who they were when they were barely pubescent. Which was fascinating just by virtue of its omission...?

And MULTIFORCE, with its wizards and battle-monsters-- it has that teenage stain to it, too, you know...?

So when you say the "context" for MULTIFORCE, I guess I think of that, too. And I don't mean this as a critique, in a "oh, comics are so adolescent-- even fancy-schmancy ones" way. But that idea that you can't be a big hit with geeks if you're not in that headspace with them, to me, was a very off-putting idea to have in my head because... Because I don't have much affection for me, age: 13. I don't like that kid-- he was kind of shitty. The stuff I was into-- it's stuff I want to feel like I've grown past. Maybe I have grown past-- I don't know; maybe not. I don't know-- and so to some extent, my inability to connect with anything lately... I feel like so many people in comics are trying to access a part of themselves that I want nothing to do with. Do you sit there obsessing about your teen years when you're sitting there writing about zombies or pleasure robots or cheerleaders or whatever the hell it is your comics are about, I haven't read any of them? Do you ever think maybe you have to be able to go to that place to hit it big in the whole comics-for-geeky-types game?

MARK: No, I don’t think consciously mine my adolescent years for artistic or commercial gain. I’m embarrassed by a good portion of the pop culture I consumed:

A long time has passed since then. And yet…I’m working for Marvel now. I saw Larry David recently and I froze up in a way I never have in front of anyone famous. And, I think you can see Tom Clancy’s influence in UNTHINKABLE and Larry Hama’s in GRAVEYARD OF EMPIRES. I did a ton of research for both those books, so I think they reflect more mature reading choices and a more nuanced political worldview. But they are still rooted in these things that for whatever reason affected me at an early age.

You more easily absorb a second language when you are younger, and I think the same is true with the art and entertainment we consume. I learned French in high school and can still speak it enough to get around Paris. I learned the equivalent amount of Modern Hebrew in college and I couldn’t order falafel. Similarly, I read Dostoevsky’s Notes from The Underground maybe four years later than the Sum of All Fears and while it blew my fucking mind it’s pretty clear which one influenced me more.

For someone who has ambitions greater than what I’ve published ... it’s frustrating. But I can’t help that I grew up watching Robotech and playing Pool of Radiance on my Commodore 64. All I can do is hope that the other stuff I bring – my education, life experiences, whatever – helps broaden the scope of the comics conversation.

ABHAY: Some things are plainly oriented towards an audience, communicating ideas to an audience, educating an audience, entertaining an audience. And we can judge them by the standard of whether they succeeded or failed in satisfying some cognizable audience need. On the other hand, we have something like MULTIFORCE where when I look at it, I feel like the audience and the audience's needs are much less relevant to how we should judge it, that maybe the idea is more so about creating something that's purely of the author, with an audience invited to spectate upon the results. (I mean, I'm sure fans of this kind of thing are jumping up and down somewhere, muttering about how much they got to participate in MULTIFORCE and bully for them, but.)

ABHAY: Some things are plainly oriented towards an audience, communicating ideas to an audience, educating an audience, entertaining an audience. And we can judge them by the standard of whether they succeeded or failed in satisfying some cognizable audience need. On the other hand, we have something like MULTIFORCE where when I look at it, I feel like the audience and the audience's needs are much less relevant to how we should judge it, that maybe the idea is more so about creating something that's purely of the author, with an audience invited to spectate upon the results. (I mean, I'm sure fans of this kind of thing are jumping up and down somewhere, muttering about how much they got to participate in MULTIFORCE and bully for them, but.)

And that interests me for a couple reasons-- one, because it's honestly so alien to me, it's so outside the realm of what I can imagine ever being able to do. You know: I write these shitty little essays with little dumb jokes in them, but ... I suppose on some level, I guess I'm always thinking about an audience. Mostly African-American men. Like... like, do you remember that one D'Angelo video? I think about that video a lot, sometimes.

And two-- I think there's a weird thing in comics where people who plainly and unmistakably make things for audiences pretend otherwise. You know, you see the interviews where people strike this affected pose-- "I don't write for an audience. I write for me and just assume that people as cool as me are out there. It takes a lot of generosity on my part to imagine it but that's what I'm willing to do." And it's like... c'mon, you write BATMAN for a living. "I don't read reviews. I'm too much of a fucking artist. I didn't read a single review for SIEGE AFTERMATH: BATMAN VERSUS THE DEATH CHEERLEADERS."

MARK: With the possible exception of some JD Salinger manuscripts that might be locked away or burned, all art is for an audience. There’s an audience that will give you lots of money for Batman on a bangbus with cheerleaders and there’s a smaller audience that’s interested in seeing what the inside of people’s heads are like. I have to think about gatekeepers – artists, editors, publishers and Hollywood types who determine whether my stuff gets made. My life is all about trying to write things that I’d like to read myself that will also get published/get me paid.

ABHAY: In the place in comics you exist at, you have to worry about building an audience, generating and maintaining goodwill with editors, potentially finding ways to exploit your properties in Hollywood-- you are constantly having to service not just an audience but multiple different audiences, some of whom may have conflicting goals or evaluative criteria. When you see something like MULTIFORCE, which at least seemingly doesn't give a fuck about any of that shit, are you jealous? Are you a little angry? Are you going to cry? Are you going to fucking cry like a little bitch?

MARK: I don’t know enough about Multiforce or Brinkman to know what his intention is in terms of entertaining an audience and who that audience might be. But given what you said…of course I’m jealous. I’d love to empty my head on the page and have it published without having to figure out some kind of high concept angle. I envy cartoonists who don’t need to rely upon anyone to draw for that reason. I envy prose writers for that reason as well. On the other hand, I’m not sure that my work would necessarily be better if it was more personal. Art is still communicative, and being forced to communicate with an audience, even if I don’t completely understand who that audience is, I think has made me tell better stories.

I think about the audience a lot-- though perhaps not as much as I should. Not because I don’t care what they think but because…quite frankly I don’t know who my readership is. I feel like I write such diverse things that I’m not sure if the same people that reading my mainstream superhero books like Teen Titans are also reading creator owned books like GRAVEYARD. I’m not even sure that there’s overlap between my different creator-owned books. Which is strange because – the comics readership is so small and creators are so accessible that I’m probably Facebook friends with a good portion of my readership.

ABHAY: There's something David Foster Wallace said in a Bookworm interview that always stuck with me. This is back in 2000, as part of the "Heartbreaking Group of Staggering Geniuses" interview series that Michael Silverblatt was doing back then. At one point, Wallace said something that's stuck with me for about eleven years now:

"Is the fundamental transaction an artistic transaction, which I think involves a gift? Or is it fundamentally an economic transaction, which I regard as cold? I think television, commercial film, commercial top 40 music-- some of which, no make mistake, I put in my time watching, these are very cold media[...]. The coldness I'm talking about-- none of this is for you. What it is, is to get you to like it enough so that certain rewards accrue to the creators and sponsors of these things. [...] One of the reasons why people react to certain things like alternative music or poetry slams or kind of makeshift art that you see in parks-- some of which is kind of ugly, but it's warm. One senses that the transactions is, for lack for a better terms, is spiritual, and is between people, and that economics and sales are not at the absolute fundament of it."

With comics... I get the impression that every comic creator thinks they're creating gifts merely because the scale of the financial rewards are so small, not just on their own terms but also by comparison to creative product in other media. (Or I feel like on the internet, there's this constant desperate chatter about "loving comics"-- I love comics, do you love comics, why do you love comics, when did you realize you love comics, what were you wearing when you realized you love comics...). But regardless of all of that, I would say that I still perceive the majority of books being created as being cold, in the DFW sense set forth above. And I don't know if that's just my cynicism, or my own lack of "warmth," or lack of spirituality, or a failing of my own "love" of comics.

MARK: The pull between art and commerce has been there forever. It’s not some new development. I guess it comes down to how you view human nature. I don’t believe anyone does anything for free. We all expect to get some kind of reward. Maybe it’s not financial, maybe it’s in return for the simple act of acknowledging someone else’s ability. Either way it’s a transaction. As cynical as that sounds…I don’t think either of us would be having this conversation if art didn’t have a transcendent quality to it. I’m the least spiritual person in the world, but I’m thankful for those moments when I’m genuinely moved by something. But what I live for are those moments when I’m in the process of writing something that moves me. All those cliché things about how amazing those moments are when a character surprises you? Or when you’ve suddenly worked something out in your writing that, for just a brief moment, makes the universe temporarily make sense? They’re true, and I’m not sure they are any less true for someone writing about Bruce and Martha Wayne getting shot in crime alley than they are for David Eggers writing about his real parents’ death.

Warmth works. Warmth sells. Spider-Man may have been cold commodified to sub-zero but there’s heart in it that still resonates beyond nostalgia. And I’d bet much of the vitriol that pours out of you is your frustration as a reader. It’s less your frustration over some aesthetic choice than it is that on some level the work isn’t giving you the warmth you secretly crave. I’ve seen you be forgiving over some things with some pretty big flaws, and I think that’s because you were moved. Had Bucky’s character had a bit more warmth to him, maybe when we saw Captain America, you wouldn’t have giggled like a schoolgirl as Bucky plummeted to his death (or into Ed Brubaker’s Commie arms for the inevitable sequel).

ABHAY: One of the reasons I wanted to talk to you about MULTIFORCE is that you're maybe one of the biggest computer game guys I know. You're always playing some game where you pretend to be a magical pixie ballerina and you wander through a dungeon killing elves, or you pretend to be a magical pixie ballerina and you run through New York City murdering hookers, or you pretend to be a magical pixie ballerina and you create and destroy your own simulated human civilizations. I just know that you've spent hour after hour, upon hour upon hour, pretending to be a magical pixie ballerina-- and for some of those hours, you've also coincidentally happened to have been nearby a computer game.

MARK: Now that you’ve outed me as one of “the biggest computer game guys I know”, I don’t feel bad about asking you about your sex life. Actually, I think that gaming is probably less geeky than comics, it’s more mainstream. But as someone who used to make paper maps for A Bard’s Tale on my Commodore 64 (thank god for automapping) I’ve always managed to get ahead of the nerd curve and carve myself out the most socially retarded niche possible.

ABHAY: More than any other reference, there's a comparison to video games that gets made when people discuss MULTIFORCE, comics like it. I was not a huge SNES guy, but there are people who look at MULTIFORCE and see, you know, that same exploration of fantasy maps that was at the heart of Metroid or Castylvania or whatever: whatever destination is at stake is irrelevant; the "reward" for the "journey" is the journey itself, getting to see more of the map, more of the terrain. Brinkman's characters-- maybe people see them as being symbol-characters that the audience is allowed to imprint on, the way Kid Icarus or whoever was just this weird collection of blocks that a certain generation of dude has this weird affection for...? I just wasn't SNES-y as a kid-- except maybe DUCK HUNT. But as far as I know, there isn't a generation of art-comix creators working out the influence of DUCK HUNT in their comics, so... based on that, I think I've quite reasonably concluded that I'm probably like a million times better than anyone who draws comics at Duck Hunt. So suck on those apples, David Mazzucchelli.

MARK: I did notice something of a game feel to Multiforce. Although those aspects could just as easily have come from fantasy novels or role playing games. Books like Scott Pilgrim or Nonplayer seem to wear their videogame references on their sleeves. There’s was an action figure influence to it as well (action figure collecting being even more of a sign of arrested development than games or comics). You’ve got these giant monsters with these modular arms. The coolest of them being the book’s star, Battle Max Ace, who has an axe for one arm and a mace for another. How could you look at him and not think he’s the coolest Micronaut ever?

Did I experience the comic as a gamer? Well, I viewed all these things as shoutouts to my various nerd hobbies. But, the comics lacks something essential to gaming which is the freedom, or even the illusion of freedom, to explore the worlds Brinkman created. There’s no choice, we’re just being led on a path, we’re on rails. Even if that path takes us through an incredibly cool world, one with very clever asides.

ABHAY: My favorite game this year is The Stanley Parable, which is a free 5-minute PC game critiquing the illusion of choice in videogames-- it's about how transparent that illusion is. The illusion of freedom with games... I mean, sure, some people play MASS EFFECT as a boy and try to have sex with the racist girl, and some people play it as a girl and try to have sex with the blue skinned girl, so it's not nothing. But I know from experience, from having played Zork as a kid and typing "FUCK MAILBOX" and every other perverse two-word combination of sex act I could muster up in my imagination at age whatever into the Zork engine-- our imaginations always are going to outpace the level of choice a game designer can ever possibly offer and so there's always going to be something disappointing about "choice" in games...

I just played that game LA NOIRE, which is just fucking terrible from a story standpoint, from a game design standpoint, from just a ... just a fun standpoint. You just wander around these apartments, picking up and putting down bottles, and that's basically the entire fucking game. "Oh, look-- it's another bottle." But ... at the same time, I got to wander around 1940's Los Angeles. That was almost enough. MULTIFORCE's geography was the same for me in that way, I guess. It's very easy to think of comics, games, etc., as just being these delivery vehicles for "stories," but... sometimes, I think maybe stories are sometimes just excuses for a chance to check out and visit some Other Place mentally for a while. Same as porn -- sure, sometimes it comes with a story, but the stories don't even end in any meaningful way. I mean, okay, sometimes, the guy'll say something like "I'm changing your astrophysics grade from a C to an A so you can keep your scholarship."

MARK: With games…I’ve generally been underwhelmed by what game critics consider a “good story”. Heavy Rain was the last game I can think of that praised for story, and while I enjoyed the gaming experience…if you took the gaming aspect out of that the story would not hold up. I think my best gaming experiences have been with games with little or no story, where I’ve gotten to impose my own narrative on it. I like coming up with my own reason why empires rise and fall in Civilization. Or…one of the best gaming experiences I had was with fellow comic book and screenwriter Jonathan Davis playing The Sims. We created a house where we populated them with Sims that we named after well known comic creators from the 90s, and watched them shit themselves into squalor.

With porn…I mean the goal is to get the viewer off. But we all have such individual erotic tastes. I mean, I might prefer cuckolding, and you might like lemon parties. And by like, I mean you crave the feeling of your dark flesh being suckled by my pale white grandfathers like it was the nectar of the gods. So the more specific you make the plot of porn, the more you shrink your audience who maybe wants the actress to take off her goddamn high heels for once. You could get V.S. Naipul or whoever to write porn and chances are he can’t come up with something that competes with our naughty fantasy of someone we had a crush on in high school or college.

Storytelling in gaming is at best secondary to the gameplay experience, and storytelling in porn is more often than not putting an obstacle in the way of someone getting an orgasm.

Here’s another question for you. Can comics be non-narrative experiences? There are non-narrative films, although those are generally things I can’t sit through for more than a few minutes as part of museum installation. Can you think of an example of a truly non-narrative comic? Because while the narrative in Multiforce is pretty thin compared to say, Watchmen, the threads of narrative are still there, even if they sometimes just exist to poke fun at traditional fantasy/gamer storylines.

ABHAY: Non-narrative comics? Absolutely, yeah, more than I can count. There was a collection called ABSTRACT COMICS that came out a year or two ago. Frank Santoro did a comic called CHIMERA that's sitting in a drawer in my kitchen somewhere, this yellow and salmon-colored thing where... there's a sort of progression to the images, so would you call a progression of images a "narrative?" Some of Derik Badman's webcomics; I don't know-- lots of stuff. You go looking through anthologies and you'll see enough "formal experiments" to choke a horse. I feel like there are periodically dust-ups in fact where people complain that young cartoonists are too interested in non-narrative based investigations into form, instead of focusing on character-based experiences...?

Except I don't know if this is the right answer though because... it's a question of what "non-narrative" means to you maybe...? That term makes me queasy because, well, comics may be inherently "narratives" just in that I think we're built to impose a narrative onto sequential images, even if one is not presented. You probably know about that Russian editor experiment where Russian editors took still shots of an actor and a plate of food, and based on how they arranged it, the audience either complimented the actor for conveying hunger or conveying disgust, something like that...? I mean, I never saw Koyaanisqatsi, with the Phil Glass music and everything, but I remember seeing MAN WITH A MOVIE CAMERA and all ... Oh, it was years ago but my recollection is that it was like your very-metaphorically-accurate SIMS game, in that I remember it being difficult not to create a narrative and push it onto the images, when presented with that montage, difficult to just accept images as images. Or it's ... It's kind of a confusing question.

ABHAY: With MULTIFORCE-- the collective impact of each page tends to be overwhelming. Each page is more than the sum of its parts; each page is constructing or demolishing some kind of other-worldly geographical space, with the story sort of forming out of these abrasive doodle-characters journeying through that space, battling over that space. And the geographical spaces sort of seem to escalate as the story goes along-- there's a forest which gives way to subterranean caverns, which give way to these giant pueblo-like stone structures connected by trains through giant skulls, etc.

And so what I suppose MULTIFORCE always make me think of is how my favorite comics tend to have that same appeal, of characters investigating and journeying through a limited space. My first favorite comic was Walt Simonson's THOR, you know, with those Simonson panels that pull back to establish the characters occupying an architectural Viking space. That being my upbringing, I admittedly thought about that facet of Simsonson more than any other cartoonist while looking at MULTIFORCE. And when I get to thinking about that kind of thing, I always wind up at the same place: how weird a thing it is that there are people who write comics. Because it seems like there are all of these pleasures to comics, so many of maybe the most pleasurable things, that I don't know that you can access as a writer. How do you ask an artist to "draw characters walking through a geographical space?"

MARK: That’s what I was saying about being jealous of cartoonists. It’s hard to enough trying to describe something like the cityscapes in Multiforce in a AFTER the fact, let alone asking someone to draw something like that in a script. Although I was a comic book reader all my life, I didn’t envision or prepare myself for writing comics as a career. Now, five or so years in, I’ve been trying to give myself a bit of a crash course in the visual arts, like with the drawing lessons. Not because I think I’ll somehow replace my artists, just so I can better communicate with them.

It’s always a balance of giving artists a clear vision to execute while giving them enough room to have fun and make the project their own. With someone like Paul Azaceta, we’ve built up trust and communication over the years to the point where I think our roles overlap. On Graveyard, he’s been intimately involved in the story and I think the roles for both of us have been blurred. I’ve had similar experiences with Salgood Sam/ Max Douglas on our story for Tori Amos’ Comic Book Tattoo, and now with a Dracula project we are working on. With work for hire, where I don’t know the artist, and when I start often don’t even know who the artist might be, I try to lay out a very specific vision. If I don’t, I’m not just leaving it to chance, I’m abrogating my responsibility in a way. I mean, almost without exception, nearly everything I’ve ever written in comics has come out better than I imagined thanks to the artist. But as a collaborator it’s pretty shitty to make the artist do the heavy lifting.

Yes, clearly there are things that artists bring to the table that writers can’t, even if they’ve got better visual art resumes than I do. But I believe – I have to believe-- there are things that writers bring to the table that artists can’t. Writing – not just comics writing – is something that’s become devalued. Partly because we all do SOME kind of writing, whether it’s a screenplay or an essay or an e-mail. And, you know, it’s not helping some publishers are giving artists writing gigs on titles as incentives for signing exclusives. It’s hard to imagine that the other way around. Add all that to the fact that…as human beings we have a tendency to impose narrative on something, whether it’s there or not. But that innate sense of story we all possess shouldn’t be mistaken for expertise in the craft.

ABHAY: I don’t know—with mainstream comics, we’re coming off this era of Writers as Stars of Comics. I feel like a sales pitch for mainstream comics was made to lapsed readers starting about 10 years ago, that “Oh, those bad ol’ Image guys wrecked comics by focusing on the art so much, but then the writers regained control and now we have stories again.” I don’t think that sales pitch reflects the reality anymore—it all seems as editor-driven and editor-suffocated as the worst parts of the 90’s to me-- but that seems like it's still the sales pitch. They’re even printing those photos of bewildered writers straight into the pages of mega-crossovers now. “Look! Look at our writers! Look at our writers trying to make human expressions with their faces! Here is proof that our comics are so, so written!”

However, when I go onto the internet, at least the people I read—they all seem much more eager to talk artists. Maybe it’s the people I read, but I know I’ve read more excited writing about Jerome Opena, Marcos Martin or Chris Bachalo than whoever's writing for them. Or I know personally, while I might have some nice enough things to say about Scott Snyder, I’m way more excited to see people react to and/or rediscover Greg Capullo…? I just think Capullo’s rad. Are you a Greg Capullo super-fan? I am. I mean, I’m bewildered by some of the artists chosen to write their own books-- sure. But at the same time, the idea I’m going to enjoy a JH Williams comic an iota less without some of the writers who've written for that guy… well, with my tastes, let’s just say that seems unlikely to me.

But say hypothetically you loved MULTIFORCE-- could you and Paul Azaceta have teamed up for MULTIFORCE 2: MULTIFORCE TAKES AFGHANISTAN? Or is it like... like when I hear rap music, where I just go, "Oh, I can't do the rapping so I guess it's a good thing that poverty exists, after all." The fact I can't rap doesn't diminish my ability to appreciate the rappings of other people-- we all just have to shine in our own special way...

MARK: Would I write Multiforce 2? Abso-fucking-lutely.

I was talking with a creator at Comic-Con about that rumor that keeps resurfacing that someone’s finally going to give a go ahead to write a Watchmen sequel. He said he absolutely wouldn’t do it, which is the stance of most sane creators. And I said I would. Not for the money or the press-- I’d be the guy who forever shat on the patron saint of modern comics. I’d do it for the challenge. And that’s the same way I’d feel about taking on Multiforce 2. How could I make it work in a way that honored the original experience and yet was something new enough to ask someone to spend their time and money? Which, I think, is basically the approach I take to comics. Most obviously that’s the case with work-fire hire corporate jobs. But any time I’m dealing with a genre that’s been done before (which is all of them), that’s how I approach it. I’m sure both experiences would be utter failures as art, but I can’t imagine they’d do anything other than make me better a better creator. Even if it’s so I know what NOT to do.

The most lasting, the most resonant stories in any medium are ones that follow the same dramatic structure Aristotle and Shakespeare and Chekhov perfected. Their genius isn’t diminished by the fact that they needed actors to fully realize their vision, and it wouldn't be diminished if they needed artists to realize their vision. Three act structure, the fundamentals of comedy and tragedy and melodrama etc. are as essential to a good comic as anatomy or perspective, even if they aren’t as visible.

So yes, I’m jealous of an artist’s ability to render their vision directly on the page. But even writing prose, where I do have more control, I know that there will always be a gap between what it’s in my head and what comes out on the page. Having the ability to draw might diminish that gap, but it would still be there.

WITH NO CLEAR KNOCK-OUT, THAT MEANS WE GO TO THE JUDGE’S DECISION. (AND OF COURSE, AS THE ONLY FULLY ACCREDITED COMIC CRITIC, THE JOB OF JUDGMENT WILL BE HANDLED BY ME, ABHAY– JUDGING IS SORT OF WHAT I DO)…

* * *

* * *

* * *

AND WE HAVE A UNANIMOUS DECISION FROM OUR JUDGES– THE VICTOR OF THIS ROUND IS…

COMIC CRITICS.

Warm cookies, right out of the oven. The first day of spring after a long winter. Audience reaction shots from a "Oprah's Favorite Things" episode of Oprah. Lap dances. Christmas carols being sung door to door. Every episode of The Larry Sanders Show being available on Netflix at a moment's notice. Defeating Mark Sable in this installment of CREATOR VS. CRITIC is better than all of those things. It's just such a satisfying feeling, but also kind of spiritually renewing-- like, right this second, I have a pretty good feeling that I know how that EAT PRAY LOVE woman felt while she was eating, praying and lovin' on all those dicks. But as a meager consolation, here's an ad for Mark Sable's FEARLESS, which again is in the latest Diamond catalog (order code SEP110399)...

TO BE CONTINUED...?

COMIC CREATORS! COMIC CRITICS! NATURAL ENEMIES SINCE THE VERY DAWN OF TIME!An enmity forged in the fires of Malice! Born to hate, living to die, dying to love, but loving to fury-- a fight that can only end one way: in the squared octagon.

A SQUARED OCTAGON MADE UP OF LENGTHY BLOCKS OF DULL TEXT THAT WE CALL...

In the CREATOR corner, hailing from the mean streets of Hollywood, California-- Mark Sable... author of GROUNDED, HAZED, TWO FACE YEAR ONE, CYBORG, TEEN TITANS: COLD CASE, WHAT IF SPIDER-MAN DID SOMETHING OR ANOTHER THAT I'M SURE WAS VERY INTERESTING, FEARLESS, and/or RIFT RAIDERS. Mark's next book is GRAVEYARD OF EMPIRES from Image Comics, with Paul Azaceta (AMAZING SPIDER-MAN, BPRD 1956, POTTERS FIELD, WATCHMEN, GOOD WILL HUNTING, LEGEND OF THE OVERFIEND). You can also see a limited-animation cartoon that Mark wrote for the movie SUCKERPUNCH online now.

In the CRITIC corner, weighing in at 160 pounds, with most of that weight in the cock, ladies, if you catch my drift (my drift being that I'm a very sad person, and I cry a lot)... you know, me. Abhay. Hey. Hello. WRITER of ... well, I wrote a pretty gnarly comment the other day on youtube. I was pretty proud about that. You can soon see Abhay in an overcoat at a theatre playing SUCKERPUNCH, recklessly pleasuring himself.

In this our inaugural Winter Edition, in what we're hoping will be a year-long battle but we'll probably get fed up with each other and/or lazy and quit before a year is up... the arena is "MODERN MAINSTREAM COMICS" and the comic at issue will be...

SECRET AVENGERS

Issues #1 through 5.

"Secret Histories"

Author: Marvel Comics, with the assistance of its employees and/or independent contractors Ed Brubaker, Mike Deodata, Rainier Beredo, Dave Lanphear, Lauren Sankovitch, David Aja, Michael Lark, Stefano Guadiano, Jose Villarrubia, Mayela Guitterez, Will Conrad, Irene Lee, Tom Brevoort, and Joe Quesada.

BUT FIRST... A DISCLAIMER FROM MARK SABLE: As a creator working – for the most part - in the mainstream, it’s hard for me to comment critically on mainstream comics. It’s a small industry. And – I’m sure you have no experience whatsoever with this, but creators can be a bit sensitive. I don’t exclude myself from that category. Nor do I think I can do better than anyone associated with this book or any other we might comment on. I say that not because I want you to feel bad for me. This is just a way of apologizing to creators/editors/publishers in advance to save my own ass. And to a lesser extent apologize to your readers if I hold back. The point of this, from my end, is to see if I can do what Matt Fraction and Joe Casey did with “The Basement Tapes” – see if a creator can speak critically about comics in the mainstream while working in the mainstream. That, and to plug the shit out of my work.

* * *

ABHAY: Let's start with the premise. This appears to be a comic about a secret political violence arm of the Avengers, which seems to be a recurring thing right now in the marketing material for Marvel comics. My understanding at least is that JOURNEY INTO MYSTERY is being sold as Loki or Thor's secret political assassination team; X-FORCE was sold as the X-Men's secret political assassination team; KOSHERSTRYKE is supposed to be about Peter Porker, Spider-Ham's secret political assassination team.

So, Mark Sable, speaking on behalf of all comic creators, everywhere, ever: what's with you people and the fucking assassination teams?

I mean, is there anything worth examining about that impulse of having children's characters form death squads? "What if Oliver North trained the GOOF TROOP to be a death squad during the Salvadoran Civil War?" Why does raping nuns and murdering peasants seem goofy to you, Mark? Or do you disagree with the whole "these are children's characters" premise because ... I'm not even 100% sure about that one anymore.

MARK: As I recall, those kinds of books were born in the 90s with X-Force, as a response to the Charles Xavier’s dream of co-existence peaceful co-existence or whatever. And, more likely, as a response to the market’s (perceived) demand for darker, edgier material. I see Secret Avengers, though, as being more of a product of creators, myself included, who love crime and espionage. Some of whom would rather just be writing straight crime or espionage, but the only way they can tell the kind of story they want in a commercially viable way is to tell it in a superhero context. I think it’s been more successful creatively with crime than espionage. Gotham Central was a better book than Checkmate, for example.

To throw the question back to you– can espionage work in comics? I ask whether straight espionage can work because I’m not sure superhero-espionage can. There’s something inherently gaudy about superheroes that seems to work against it. Secret Avengers starts with Black Widow and Valkyrie posing as escorts trying to gather information from a businessman in Dubai. Before you know it, Steve Rogers is swinging through the window in a Fury-esque outfit with a big star on it and a laser shield. So it’s like the characters themselves can’t even maintain the charade of espionage for more than a couple of pages.

It’s an odd choice for me too to have Steve Rogers lead a black ops team in the first place, him being the moral compass of the Marvel Universe. Of course…in my mind, the fact that Captain America has a code against killing is absurd in and of itself. He’s a soldier, and that’s what soldiers do.

And yes, I absolutely disagree with the whole “these are children’s character’s premise.” Well, let be a bit more specific. They are children’s characters so far as merchandising goes. I think it was Tom Brevoort who pointed out that most kids are introduced to superheroes not in comics, but in the more kid friendly areas of animation and toys. And that’s where the real money is made in this business. Other than toy stores, the only place these characters are safe for kids is in the childhood memories of older fans. Or, let’s at least be honest. Let’s say that the arbitrary restrictions put on what superheroes can and cannot are in place to keep the brand of a movie franchise or a toy line unsullied. Let’s admit that, for the most part, there aren’t valid character reasons why certain heroes don’t kill. In a way it’s dangerously dishonest not to show that permanent death is the logical outcome of violence.

As much as superhero black-ops teams might not work for me, they do tap into something. Much of the wars we’re in are fought covertly. We sort of half-ass wars, for the most part. By which I mean…we don’t use overwhelming force, and we only ask a small number of people to sacrifice. Take the drone strikes in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Yemen. We’re quietly – meaning without much media attention - using our overwhelming force in way that doesn’t incur losses on our side but helps keeps the other side fighting because it creates more insurgents.

Maybe a book like Secret Avengers reflects that. The big guns of the Marvel Universe are sent in to deal with a problem. They never die, so the reader isn’t asked to sacrifice their enjoyment of reading their continuous adventures. The villains don’t die either, so the conflict and the story is perpetuated.

ABHAY: See, my recollection is that X-FORCE was about a band of soldiers who philosophically disagreed with the X-MEN, but that the X-MEN didn't ratify their conduct. There'd be those scenes of Storm saying shit like "We disapprove of your methods, Cable. I'm so angry I'm going to change my haircut!" But my impression of SECRET AVENGERS and these other books is that they're about the "heroes" ... acting "unheroically" when they think no one is looking...?

Does that taint them? Set aside kids. Forget about kids. On the one hand, some people say superheros are great because they show how we can create characters that our better than ourselves, characters that always do the right thing. These are fairy tale characters, and the fact they're not like us is something that's right about them. But of course, there's a competing argument, that characters should just be characters, as flawed as anyone, and not moral exemplars. Which ... I know anytime I hear a comic creator talk about the morals in their story... I'm going to take life instruction from a fucking comic book writer?

Where do you think you wind up on that? I guess having read so many Superman comics last year, right this second I'm more aligned with the former. I'm not really interested in "realistic" superheros at the moment. You know-- some people like to say SUPERMAN is "boring," but being a fairy tale character hasn't really hurt DOCTOR WHO any...?