Strangeways, Here We Come: Part 2 of A Talk With Matt Maxwell

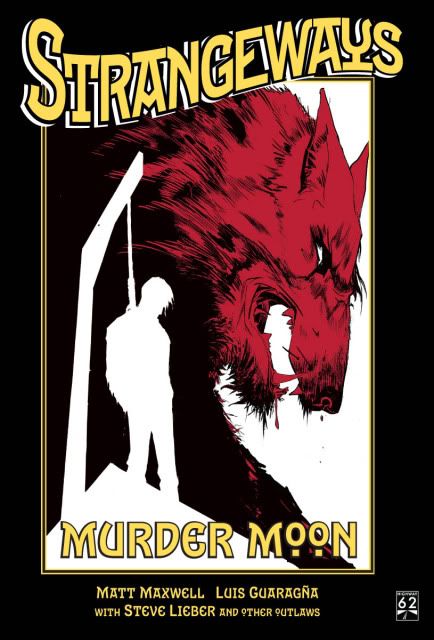

/![]() Yesterday, in Part One of 'Jeff Lester Talks Too Much,' I occasionally let Strangeways writer Matt Maxwell get a word in edgewise, and talk about his book Strangeways: Murder Moon, the current serialization of the second book, Strangeways: The Thirsty, on Blog@Newsarama, and writing for comics.

Yesterday, in Part One of 'Jeff Lester Talks Too Much,' I occasionally let Strangeways writer Matt Maxwell get a word in edgewise, and talk about his book Strangeways: Murder Moon, the current serialization of the second book, Strangeways: The Thirsty, on Blog@Newsarama, and writing for comics.

Today, in Part Two, Matt talks about writing for comics, rewriting, self-editing, bad comics that are awesome, and awesome comics that are awesome. Like Part One, I talk too much, and the article should be cut into more than two parts. But I wanted to make sure this all went up before the weekend and not lose the momentum.

Behind the jump: Part Two.

JL: So, Strangeways. Where is it going, generally? The first one is werewolves. The second is supposed to be a turn on vampires? MM: The second is a turn on vampires. I know what the third one is, I won’t tell you yet.

JL: I think that’s fair enough.

MM: Actually, I’m working on the page beats for that. That’s a slow process, though. That’s the most time-consuming part of this. Once you’ve done the page beats, the script pages go fast.

JL: How do you work that out?

MM: I bang my head against the desk until something comes out. Unfortunately—well, not unfortunately; it’s good that I’m busy—but I’ve been spending a lot of time doing lettering for the second story, getting the files ready to go up on the blog, and then I need to start doing marketing stuff before the book even comes out, and it’s still not even officially scheduled! I’m hoping for late next spring, or early next summer, and I’ve got to do a lot of legwork before that in terms of getting books to retailers and that sort of thing.

JL: Do you think that’s going to be easier this time around than the first time? Because you’ve got the product out and they’ve seen it? MM: You know, I don’t know. In terms of people knowing what they get, I would hope that having everything out on Blog@ would certainly make that easier. When I was doing the book when it was going to go out of Speakeasy, I did ashcans and I sent them out to Jeff Mason’s indy-friendly comics store list. Which I assume bumped orders, because the book was solicited, and I’m assuming it was actually ordered even though it never shipped, which I still regret to this day.

JL: I think it would be a very interesting different path if that had happened for you. For better or for worse.

MM: Yeah. It would’ve been late, then. Unfortunately, the fourth issue would’ve been quite late, so maybe it’s better. And I thought I was doing having effectively two issues done before they were started being solicited.

JL: So what would you think be the sweet spot for that, seventy-five percent?

MM: I don’t know. The guys I work with in terms of art are generally consistent but I think there was some extenuating circumstances on that fourth chapter of the original Strangeways book.

But no, I need to spend some more time writing very shortly. And yes, there is a place for everything to be going, but I think the first few stories are going to be more probably action-focused. I’m hoping that a lot of character stuff came through. Depending on who you talked to, it did or didn’t.

JL: I thought the character stuff came through in the first book. I didn’t get as strong a resolution in the story upfront. In fact, what I thought was interesting was reading the back up story in the trade was great but it was vexing in that you saw the motivation for the antagonist, and I remember thinking that second part worked very, very well, but it was almost like you ended up bifurcating the narrative. MM: Yeah. In some ways, that was an unintended side-effect of a, some would say, crazy plan of giving you more of the ‘bad guy’ side of the story. Like Lee Marvin said when asked by an interviewer, ‘How do you feel having played bad guys your whole entire career?’ He said, ‘I’ve never played a bad guy once. I don’t know what you’re talking about. I’ve played strong characters who knew what they wanted, and did what they needed to get what they wanted, but none of them were ever bad.’ And I wanted to show that even the bad guy’s got his reasons for doing what he’s doing, other than just being a complete jerk, just because he’s a monster—in Rale’s case, literally.

JL: It was interesting to me, because it ended up such a strong narrative that it made me think I was—and I may well have been—missing something in the front end of the narrative. MM: Probably not. It ended up being more Rale’s story than Collins, when you take it as a whole. When you’re doing a long narrative arc—and I have a long narrative arc planned out for Collins—but I can’t do too much of that, or pretty soon he stops being the character that ends up being these adventures in these places. So I don’t want to wreck the character just yet.

I plan on wrecking him, but not just yet.

JL: That’s good to know. It was just slippery enough—and I think the idea of when you’re doing a monthly book, it’s pretty easy for the reader to nail down the idea of ‘Oh, this character’s going to be back and there’s more that they’re going through.’ But I definitely put down the book going, ‘Wait, is that…it?’ It’s almost like the entire narrative was wrapped around something I couldn’t see, and I didn’t know if it was there, and knowing that Collins’ arc continues might open that up. MM: Yeah, this was an introductory arc. I can give it away and you can read the last five pages of that story, and that’s the point. And the fact I even have to say that is kind of sad. Because that means I’ve failed. It’s like explaining a joke.

JL: No, no, no…

MM: If you have to explain a joke, then you didn’t tell it right.

JL: But there are some stories where it counts on you going back and re-reading it. And that unfortunately was my big regret is, somewhere in my apartment is the copy of Strangeways that I read and finished, but when I went to go back to it recently, I was inundated with a ton of other crap.

MM: Yeah, I see you’re reading comics again. I see that on the Savage Critics. Or at least that you’re writing about the comics that you read.

JL: Exactly. I really start feeling guilty when our site lies fallow, and it’s also a little bit of a dodge for me. I’ve finished the first draft of a novel, and I really need to do a second draft, and there’s a lot of stuff that needs to be fixed, and I don’t really know how to go about fixing it, and I don’t really know how to go about tackling it. MM: Rewriting is never as much fun as writing.

JL: I think for me it’s just a vast mystery. I can only see the choices I’ve made. I have an infinite amount of ideas, but once I put something down on paper, though, it becomes set, and it becomes really hard for me to change it. I’m really good at looking at other people’s work, but I think the challenge is looking at your own and getting outside what you intend, and being able to see how it’s actually going to come across to new eyes. MM: That’s not easy. But I’ve always been a ‘go with your own instincts,’ rather than overthink things. But I can go both ways. I can overthink anything. Occupational hazard.

JL: I think it’s an advantage. I think you seem well-placed if you can do both. Too many people fall into one or the other. I’m fascinated by watching someone like Bendis work, where I get the sense that he’s also a ‘follow his first instincts’ kind of guy, and it seems to have a lot of difficulty…if it doesn’t work out, he’s kind of like, ‘well, this is what you’re going to get and trust me, it’s great.’

And then there’s other people where you get the sense—I get the sense with Rucka, a little bit with Brubaker—that they come back, they finesse things as they go. Or even perhaps in advance before it starts coming out, they’ve got a pretty good idea where the turns are all going to go and they’re going to make sure that everything is placed right.

MM: Where I pretty much know where you’re going to get to at the end. I’ve got the A, where you’re starting, and I’ve got C, where you’re going to get to. But B? It’s all over the map. And that’s… not always a good thing.

JL: That is hard. You read screenwriting books, and inevitably Act Two is the one that kills the writers. MM: If you’re following the formula, in Act Two you can have the most freedom because all you have to do is: rising action comes to a climax. Okay, well, great. Infinite flexibility is good and bad. If you don’t have discipline, then infinite flexibility is terrible.

JL: It will kill you off.

I did want to recommend for story beats, maybe, if you’re looking for something that may or may not make things easier: I ended up picking up this program Mindmanager, which is a visual mapping…

MM: I’ve been looking for a visual outliner. I can make outlines, I guess, in Excel, but it’s really easier to do them just long-hand. But I try not to do anything longhand, any more.

JL: There’s a free version I haven’t really messed with. The Mindmanager is a little costly because they’re trying to it as a… MM: A big organizational tool?

JL: Yeah. So I dropped the coin on it when I was feeling pretty flush after the Sam & Max stuff, and it’s been great, but the price makes it really hard to recommend. But there’s a free, I think there’s a free online software program—that may or may not work for you. [Ed. note: Mindomo]

But what I found was great was being able to type down all the events of the story, and then I could drag and drop them to each of the pages, which really gave me a flow of how things were supposed to happen.

MM: What I really do is, I’ll just open up a new Word file and then—if I’ve already got the basic plot in my head—and I’ll just start writing this kind of bastard form. It’s not quite prose and it’s not a script, and it’ll end up being a paragraph of what I think will be on a page.

Now, that’s not always reasonable. It’s like, ‘oh yeah, that’s really four pages right there, and two of those need to go away. So, yeah. We need to fix that.’ And you just try to break it into page-sized chunks before you even start writing the script. And then I’ll…I say I’ll go back and refine it, but what I usually do is, I end up throwing it away and then redoing it, and it’s usually much closer to what I need for page breaks.

And sometimes that’ll have little bits of dialogue, and sometimes it won’t. Sometimes if there’s a line that I think will work really well, then I’ll try and throw it in. But a lot of the dialogue happens much later in the process.

And that just takes discipline, which I don’t always have.

JL: You really have to be able to lock yourself away from everyone and everything, because sooner or later, you’ll get so bored you’ll have to start working on it. I found that’s how it works for me.

MM: Only if you unplug the Internet first.

JL: Which I’ve had to do. Not so much for the comic scripts, because the comic script stuff is so formalistic for me. I mean, I’ve only done a ten page story and an eight page story. MM: And at that point, you’ve got no room to deviate. You better be on what you’re doing, or you’re going to be in trouble.

JL: So I can be really plodding with that—to me, writing a comic script is like creating a crossword and doing it at the same time, in that sort of format. I’d be really curious to jump to a longer script where it seems like there’s so much freedom to breathe. MM: You think that until you start realizing what you have to put in. Again, that’s why Strangeways ended up being so dense is—there’s stuff that I—probably ill-advisedly—added in when I was writing. ‘You know, we could use a little subplot here,’ and those ended up not getting fleshed out enough. Maybe they were interesting and engaging to read, but people walked off thinking, exactly like you did, ‘well, maybe I missed something with the connection between this character and this character here.’ I try not to insult the reader’s intelligence but there are times where I probably don’t give you enough of a roadmap. But that’s something that comes with time.

JL: That’s always the problem. Just getting a skeleton into the format seems miraculous enough, and getting it fleshed out enough to where people really care about the movie. So not only do you have to communicate it, but you have make people care about it. That’s where the challenge really comes in. It’s enough of a challenge just to tell a story in comics, which is something I do find fascinating about the form.

Having written a script, I really see why people screw this up left and right. It’s unbelievably easy!

MM: It’s not very hard at all to mess things up. It just isn’t. Even when you have an editor saying, ‘Hey, dude. You’re messing this up.’

JL: Exactly. Which—you’ve always worked unedited? It’s always just been you keeping track on yourself.

MM: Yeah, and there’ve been people, ‘You know, that’s not really a good idea, Matt.’

[pause]

I still talk to them.

But I don’t know too many comic book editors, and frankly I’m not in the position with the second one—the second one is going out as-is. It’s not in a point where I could fix anything. I’ll try and fix the dialogue, but the art I’m getting is what I get.

So if you’re going to do editing like that, you really need to do it at the script stage before any art gets worked on at all. And that’s not always possible.

JL: And then there’s the problem… I think the part that just would be sort of brutal would be, you write the script, the art comes back, something gets missed or misintended, and then you’re in the position of—I assume—not having limitless funds, you can’t turn around and go, ‘hey, by the way…’ MM: If I have the guys make a change, it’s because the change really needs to happen. If it’s ‘Oh, it’d be a little better if we did this?’ No. You better pick these battles. I’m paying these guys but I can’t pay them a lot. But I pay them and I pay them on time, but there’s some things that will have to happen with your story, and if they get something wrong then it’s gotta get fixed. There’ve been very, very few things I’ve even had to call them on, much less…And Luis especially has come back with a number of redrawn panels, months after he’d submitted the original. And the redrawn panel is not a big deal if he’s just tightening things up. That’s fine, I’m glad he showed the initiative to do that. But if he restructured a page, then I might get a little grumpy if I’ve already lettered it.

I don’t know. In some ways, I wish I could do more formal experimentation but I’ so concerned about my ability to tell the actual story that I’m pretty conservative when it comes to trying anything crazy and wild.

JL: I think you just have to hope that later on you will have the freedom and, by that point, you’ll know the basics. MM: It’s the whole thing about learning the rules of grammar before you decide to go break them. You can’t just sit down and do stream of consciousness because Kerouac did it that way, or Joyce did it that way.

And, actually, Kerouac didn’t do it that way in the first place. My understanding is that the typing on the roll of the paper [for On The Road] was actually a myth, that there was an original manuscript and it was regimented by the page just like everybody else’s. Maybe there was a first draft where he just spit it all out.

JL: There’s always a stage where there’s a blank page and you have to sit down and attack it. MM: The script stage is not the blank page for me. The script stage is where I’ve already done most of the work. It’s the page beat that’s the really intimidating blank page. That’s where the work is.

But a chapter of a novel is as long as however long it needs to be. You just paginate it.

JL: The novel process is freeing like that; you go through problems of too much freedom, depending on how much you want to indulge it. For me, I want to do the second draft so hopefully people can have the enjoyment of the experience that I had while writing the first draft. Because the first draft of the novel, you really do have the freedom to discover the beats of the story while you’re going around. And then if that takes a twist, that’s great.

A lot of people don’t work that way. A lot of people highly recommend if you want to get your book done, outline it and then attack it. And that seems great, but it just locks me up.

MM: Huh. Because the first novel I wrote was something called Blue Highway—which I may be revisiting—but it was originally I did it as a very bad screenplay. I mean, bad, bad, awful screenplay, which I wrote in like two and a half weeks, and then a few months later I started writing it as a novel and went through it pretty quickly—a six month draft process while working a fulltime job.

JL: Wow, that is quick.

MM: Although I was able to write at work, so don’t tell my boss.

JL: I’ll keep it between us.

MM: This isn’t going on the Internet or anything, right?

JL: No, no, no.

MM: Okay.

JL: Like I said, my hope is to type this stuff up, and then…

MM: Well, I haven’t worked there in years.

JL: I don’t think you’ll have worry about your ex-boss googling your name, and going: ‘Matt Maxwell: Thief!’ MM: No, I haven’t worked for that company in some time.

JL: What do you currently do, Matt? Just this, or do you have any other thing?

MM: I’m a dad. That’s far more work than any job.

JL: My understanding is that the pay and benefits are still a little on the lower end, though. MM: Yeah, if you look at it by the hour? Boy.

Much like writing, you’re pretty deep in the hole if you parcel it out by the hour. But when you’re on the duty, it’s tough: I know there are guys like Jason Aaron, and I’m pretty sure he has a job too, in addition to writing. And I don’t know how he does it.

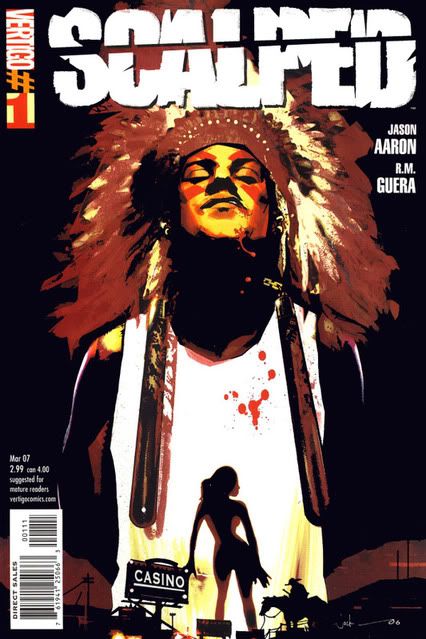

And he writes—I mean, if you aren’t, you should read Scalped.

JL: I gotta give it another go.

MM: It’s really, really good.

JL: I read the first few issues and I was like, ‘there’s no reason I shouldn’t love this, and there’s something that’s just not clicking with me.’ And I don’t know why. Because it’s all good, it’s all strong, it’s very lean, it’s not… MM: It’s not indulgent or flabby.

JL: Yeah, it’s practically the opposite of indulgent, in that regard.

MM: No, it’s very disciplined.

JL: Absolutely. And yet for some reason… So I’m gonna pick up the trade in the hope that the single issues weren’t giving me enough…something? MM: With single issues, I’m pretty cranky and demanding at this point. Unless it’s a done in one, it’s very hard for me to buy a story in serial issues. Even if I really like the story, it’s just a hassle. It’s a bother. I get to the end and I want to read more, and I get frustrated.

JL: I don’t have the problem too much, and I do feel it’s sort of… The problem with single issues is, it’s kind of like watering the lawn. It’s not as pleasant as it used to be, and it is a little bit of a chore. But unfortunately I also feel it’s a necessary chore, because the marketplace won’t survive if you don’t have somebody buying the single issues. And unfortunately, the more that—well, we’ll see where it goes.

On the one hand, what’ll happen you’ll get to a situation where—I almost feel like part of the reason is clogged with a lot of crossover big event junk is that, that’s what the people who’ve stayed in the single buying marketplace are buying. And everything else is treading water and waiting for the trade, and at some point that may or may not have…If you’ve got a publisher who is long-term enough, something like Vertigo looks at a title and thinks, ‘Okay, this title is not what we consider a profit, or used to consider a profit, but we’re going to keep at it because the return on the trades is good.’

MM: Yeah, there are a number of titles like that. Or, at least, that’s the conventional wisdom: I have not looked at the numbers, assuming the numbers are even reliable, to confirm that. And I don’t know about the bookscan numbers for books that are, frankly, that far down the list in terms of overall sales.

But evidently, the publishers are doing the tracking and they’re able to decide.

JL: It seems to work for everyone, but I do worry that as the market changes—particularly because I always feel like I’m the last guy to get the cellphone, if I feel like I’m always the last guy, and I stop buying the single issues, then what happens?

On the other hand, I currently have more stuff than I can review, and almost more stuff than I can read. I’m so far behind on so many titles. I’m dying to sit down and read Daredevil, but I don’t think I’ve read the last ten to twelve issues I’ve bought. And I either have to, or really admit that I should stop buying the singles and throw my money out into the street where I can at least know that I’m directly throwing my money away.

But there’s a lot of stuff. It’s like doing the reviews this last week. It was like, doing one and two, and then I started reading more, and I just didn’t have the time to do all the reviewing.

MM: And really, does most of the stuff merit a review?

JL: There’s plenty of stuff that, just looking at it critically, doesn’t. But there’s also times you feel obligated. Definitely my schedule has changed, so it’s not like I’m going to sit there and review every book that I read. But there are ways in which books that suck can be instructive, and it can be instructive to say why they’re sucking. MM: And books can still suck and still be vastly entertaining.

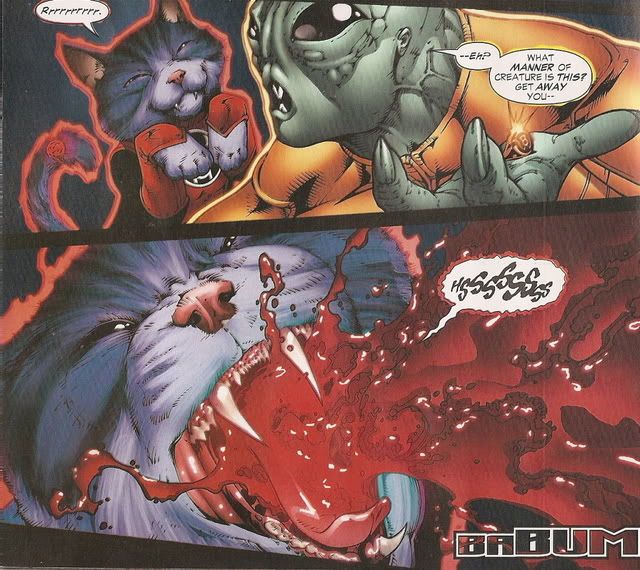

JL: That’s why I feel bad about my review of Rage of the Red Lanterns. Because to me it’s so inept it’s practically entertaining. And I didn’t really convey in my review that, ‘wow, this is really terrible, but…’ MM: At the same time awesome?

JL: Yeah, you can’t believe you’re reading it while you’re reading it, and that too is part of the reason we come to comics, not believing that somebody is actually going to put this page. MM: The Fletcher Hanks comics by any objective measurement of art quality are dreadful. But they are compelling, brutal. They demand attention.

JL: They really do.

MM: All that, and they’re batshit insane. They’re absolutely off the rails, even by the standards of the Golden Age comics which were off the rails.

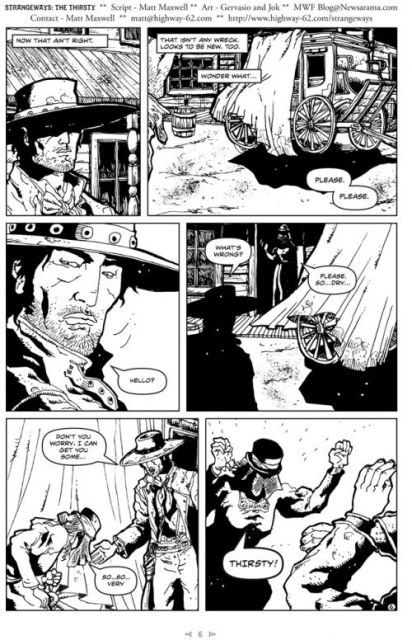

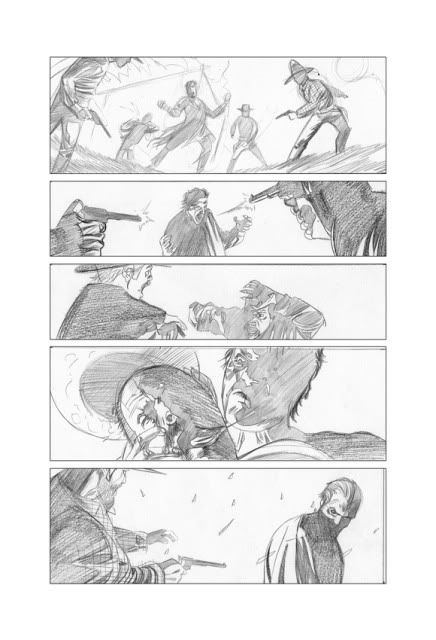

[Art: from top to bottom--Page 6 from Strangeways: The Thirsty, art by Gervasio & Jok; Page 7 of The Thirsty by Gervasio & Jok; Page 8 of The Thirsty by Gervasio & Jok; a page, also by Gervasio & Jok, from an unpublished story which Maxwell hints may be appearing in a Strangeways anthology; a page from the back-up story in The Thirsty, art by Luis Guaragna; the cover to Strangeways: Murder Moon by Steve Lieber; the cover to Roberto Bolano's 2666, released just this week in English; the cover of Scalped #1, and interior art from Rage of the Red Lanterns #1.]