And now, a short review.

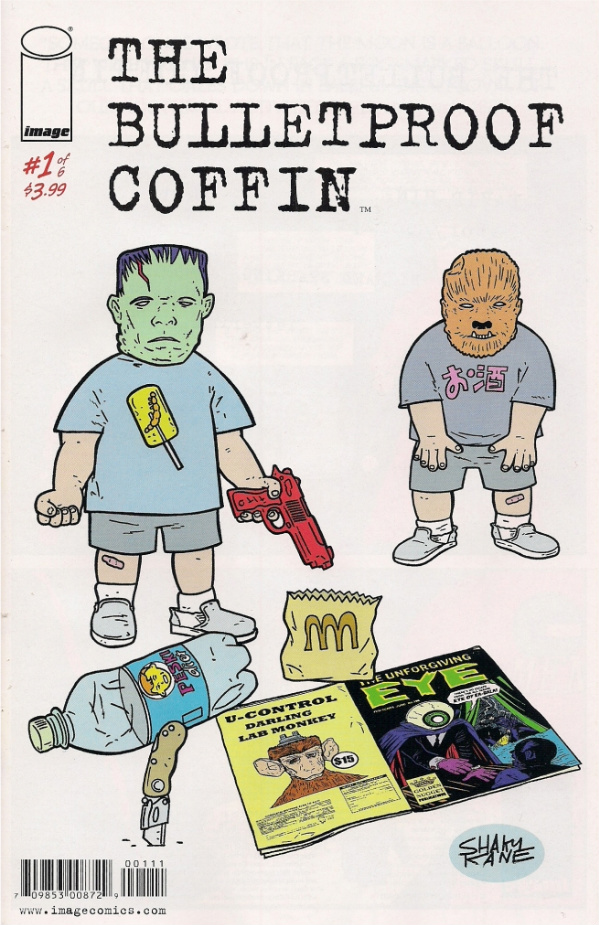

/The Bulletproof Coffin #1 (of 6): This is, on one level, a comic about comics. As our own Abhay Khosla recently said: "I don’t know– do you think that’s interesting, comics about comics? Me, not so often." But me? A little more so.

What sets The Bulletproof Coffin apart from the rest of the pop comics-on-pop comics pack is that it positions itself as genuinely radical in embracing some rather vintage, potentially anathematic ideas about self-expression, and thereby carries the potential to upset. It doesn't particularly play fair either, nor does it seem to even want to - there's a lip-smacking, facetious undercurrent to much of the commentary in this first issue, nonetheless presented with such eccentricity it registers instantly as forthright. And this tone is so odd and delicate its potential shortcomings act as their own thrill for this introductory chapter, juicing up an old fashioned funnybook critique so that it somehow feels like it can go anywhere.

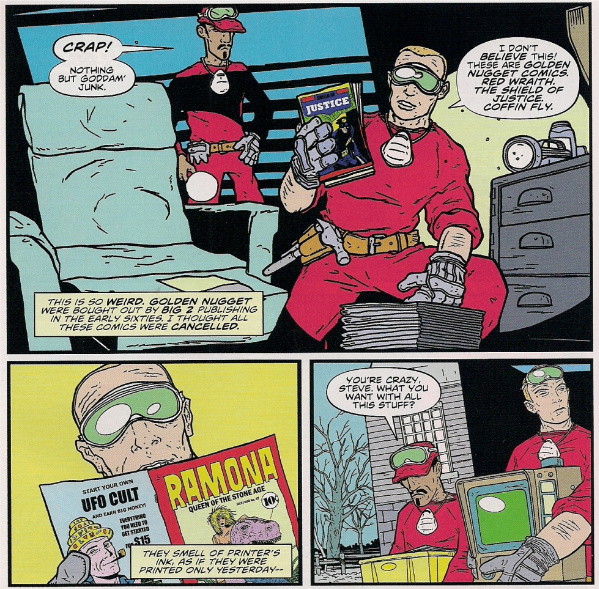

The plot is very simple. Steve Newman is a voids contractor and avid collector of pop culture ephemera: he hauls garbage out of the homes of the recently-deceased, but keeps the good garbage for himself, provided there is no verifiable auction value. No speculator our Steve - he's in it for the love, or even the life, posing heroically in his colorful work jumpsuit ("G-Men" brand prominent) before exploring a clip art-perfect spooky old house, only to return home to a listless, vacuuming wife, fast food ketchup-stained twin boys and a family dog with spiky red hair and no genitals. Temporary solace comes in issue #198 of "The Avenging Eye," a vintage Golden Nugget horror comic the price guide insists ended with issue #127. The mystery deepens when a coin-operated television broadcast maybe reveals the murder of the comic's prior owner, an old man with a Golden Nugget superhero's costume stashed under the floorboards. Can these weird events have something to do with the publisher's legendary 1950s/60s writer-artist team, Shaky Kane & David Hine?!

Of course, Kane & Hine are the British creators of The Bulletproof Coffin itself -- Kane handling the art, Hine writing the script, but both credited with "story" -- neither of them quite old enough to recall the salad days of American Code-era chillers, nor even from the correct country. The start of it, then -- the first layer of commentary -- is that distinctly American strands of comics have been imbued with a near-mystical, life-changing force, propagating a complete alternate reality for the devout - it's like alien technology, and Kane & Hine imagine themselves as cosmic commanders, masters of the universe.

That alone isn't so unique, but the creators complicate matters by also acknowledging their own real-life works and personae: Kane the elusive, art-focused contributor to Escape, Deadline & Revolver (with later, intermittent forays into 2000 AD), and Hine, writer and/or artist of assorted fantastical British works and author of the expansive horror comic Strange Embrace turned script man for various front-of-Previews superhero franchises. As hero Steve enters the spooky house, rooms are lined with items from prior Kane or Hine projects, like totems warding off danger.

This quality is made explicit in the 'historical' essay in the back of the book, even as the creators' histories erupt into burlesque. As eager Hine arrives at Kane's door in 1956 full of ideas, the already-veteran artist growls that comics are bought for pictures, not what's in the word balloons. Nothing in particular happens to rebut that idea, even when the malevolent Big 2 Publishing buys out Golden Nugget's line to gut the place of Kane/Hine's vibrant horror, fantasy and bugfuck costumed hero work: Kane becomes a legendary comics mega-recluse combining Steve Ditko and Jack T. Chick elements with Russian porno produced under the name "Destroyovski," while Hine produces Big 2 superhero scripts for the "Z-Men" (setting up an amusing alphabetical continuum of quality with the G-Men farther up and Kane's own A-Men up front), including a desperately mediocre event crossover titled (oh dear) "Final Meltdown."

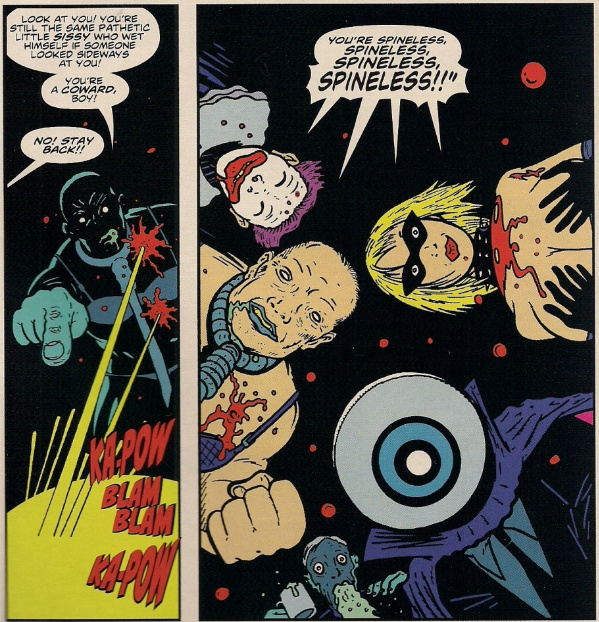

Eventually, the pair (allegedly) reunite as old men and (allegedly) set about reviving all their old properties in defiance of Big 2 copyrights. Indeed, eight pages of The Bulletproof Coffin #1 are devoted to one of these new stories, a perfectly blunt horror short about the dead exacting revenge on a weak man who murdered them in stealth, keenly blending Kane's real-life early 21st century horror endeavors from Black Star Fiction Library with in-story Hine's bottomless shame over having surrendered his principles to crank out superhero scripts, actually scripted by the man who wrote last week's Detective Comics.

It's perfectly bananas, delivering strident satirical messages -- snorting at the very idea of interesting or personal or relevant work even conceivably existing at Marvel or DC and then doubling down to lampoon the very idea of comic book writers -- in a style rife with insane self-deprecation or aggrandizement (Kane is at one point compared to Michelangelo) and industry criticisms that appear self-evidently contrived to fix wild old superhero and horror comics as the true state of vibrant comic art, vs. those multimedia-scrubbed corporate bozos who apparently haven't accrued a clattering enough mechanism of generic expectations to produce Justice League: The Rise of Arsenal.

Yet there is a richness to this seemingly on-the-nose-if-maybe-sarcastically-so lampoon, tucked away in Shaky Kane's art. More so than anyone working in Deadline, Kane was concerned with graphical qualities, and visual tropes as personal symbolism; look at his A-Men from that magazine, and you'll see a properly (John) Wagnerian costumed ass-kicker as faux-heroic icon of oppressive law transform rapidly into series of cutting, personal images, mixing comic book signals and Kirby gestures into readable mystery collage. It's precisely the opposite of Big 2's Z-Men, presumably writer-run, editor-managed and continuity-bound, enough so that in-story Kane's hyperbolic distaste for writers makes sense; what worked in A-Men, it's very center of being, was something writing couldn't dictate. There a revealing bit of Frank Santoro's Shaky Kane cover feature in Comics Comics #4, where Kane mentions that outside scripts would ask him for Kirby tribute-style art, and "it fell to pieces" almost all the time - he wasn't trying to become the King on a moment-to-moment level, but absorbing and reflecting the stuff that resonated, personally.

Kane's art is more direct in The Bulletproof Coffin -- as it was in Black Star eight years ago -- full of bright popping colors and clean panel arrangements, but still possessing a lumpy, rather boldly posed character to the figure work (a few pieces even seem to be cut 'n pasted from panel to panel) that gently reinforce their status as graphic elements in tilted perspectives and too-close zooms. It really is a whole world of artifice here, but meaningfully and mysteriously so, because odd foreign comics can be meaningful and mysterious for impressionable minds. Can't you see it in manga? Here we see it in the Silver Age, shone back at us.

All of this is naturally only a reaction to issue #1 - things can change quickly, especially as far as satire goes, especially with one this mannered and conflicted. Certainly the suggestion is made that artist Kane isn't much the same without writer Hine -- hint #1 is in the credits box -- and interviews suggest the series' looming threat isn't nearly as simple as a hard-scrubbing corporate superhero monstrosity wiping out The Best Comics Ever, Which Are the Genre Comics We Loved From Back Then. As I said up top, this is delicate work, almost private, enough so that it could be a total banal disaster or something inscrutable, or just wonderfully unexpected. I have no idea where this superhero-tinged commentary comic is headed, and damn it all I value that.