My Life is Choked with Comics #19b: Manga

/![]() (Being part 2 of 2 in a series; part 1 is here)

(Being part 2 of 2 in a series; part 1 is here)

***

III. JAPAN, HIDE YOUR WOMEN!

I'll ask it again, this time with feeling - what the hell is manga? Or more specifically, what the hell is manga today, in comparison to Western professional print comics?

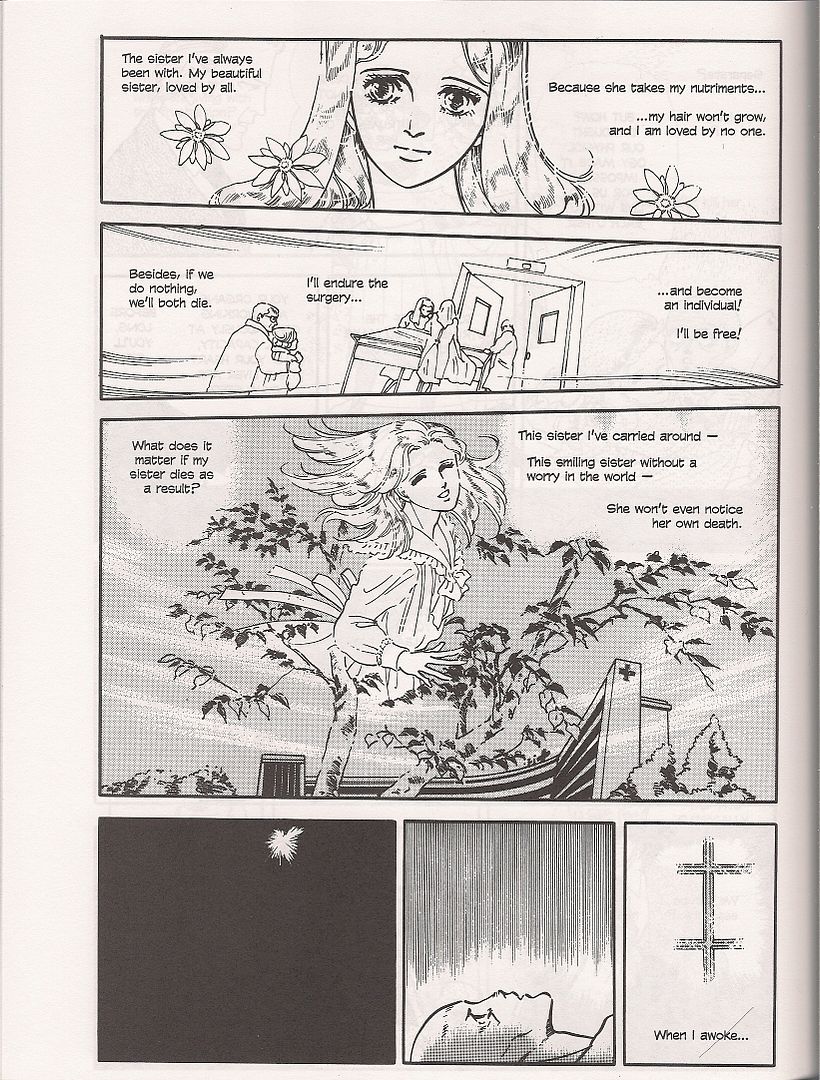

(from Hanshin, as presented in The Comics Journal #269; art by Moto Hagio)

(from Hanshin, as presented in The Comics Journal #269; art by Moto Hagio)

There's matters of presentation and distribution, of course. I've mentioned that before. Manga is digest-sized paperback books, usually serialized far away from Western eyes in terms of venue -- anthology magazines, usually -- and often time, in that even the most popular current series have to wait several months for translations to finish or licensing terms to play out. This contrasts with the typically larger, bookshelf-ready originals of the West's dominant Franco-Belgian and American traditions, or U.S. pamphlets swiftly collected into fatter tomes.

Moreover, narrowing our focus to North America, manga is also the stuff that takes up the most space in big box bookstores, as opposed to the books that line most shelves in the Direct Market. Manga usually reads right-to-left, as it's been for as long as it's taken up the aforementioned space in your Borders and Barnes & Noble, while North American comics should ideally go left-to-right, barring some formal experiment and/or deadline catastrophe; the split doesn't get any smoother than that. Hell, if superhero comics are an especially large subset of popular action comics, then popular action manga can even be seen as a bulwark of 'cartoony' artwork against the preference for 'realism' in so many Marvel/DC series, though obviously these designations aren't absolute.

What is of paramount importance, however, is the word popular. If there's anything I hope I've established by now, it's that manga isn't monolithic, that many styles and approaches exist, that manga is big - enough so that an anthology like Manga could effectively excerpt a nation's comics output in the early '80s so as to arrive at something similar to what was preeminent in North America around the same time, possibly as a stratagem for presenting an unfamiliar, foreign kind of comic as not very different from Western funnies at all, except with samurai and stuff. 'Cause it's Japan!

Today, everybody knows something deeper about manga, if only that manga is a deeper something. It's big and present; it might not show on every Best of Decade list from every visible North American media outlet, but you can bet your ass a disclaimer will be provided upon request begging off coverage for lack of familiarity, because manga will not simply be ignored. You see manga everywhere in a way you don't with other professional print comics, like Fort Thunder-inspired bookshelf collections or superhero pamphlets for kids.

Ha - I bet you can already see how I'm comparing segments of the North American comics scene to a whole nation's output, covering decades of time. In my defense, I'll say that some types of manga remain far more prolifically translated than others -- long form pop comics for boys and girls, generally, followed by a little bit of stuff aimed at older men and a smattering of projects for mature women, with individual publishers specializing in 'classic' or 'art' or 'dirty dirty smut' manga -- though surely the picture presented ten to thirty steps away from your local Seattle's Best caffeine counter hews closer to what's actually most visible in Japan than what was seen in Manga-the-anthology, very far away indeed from the shōnen style evidenced in those 2,850,000 copies of One Piece Vol. 56 on new release day, or the attitude that would prompt an Eiichiro Oda to declare a triple-digit intent for a comic weighing in at 200 pages per compiled pop.

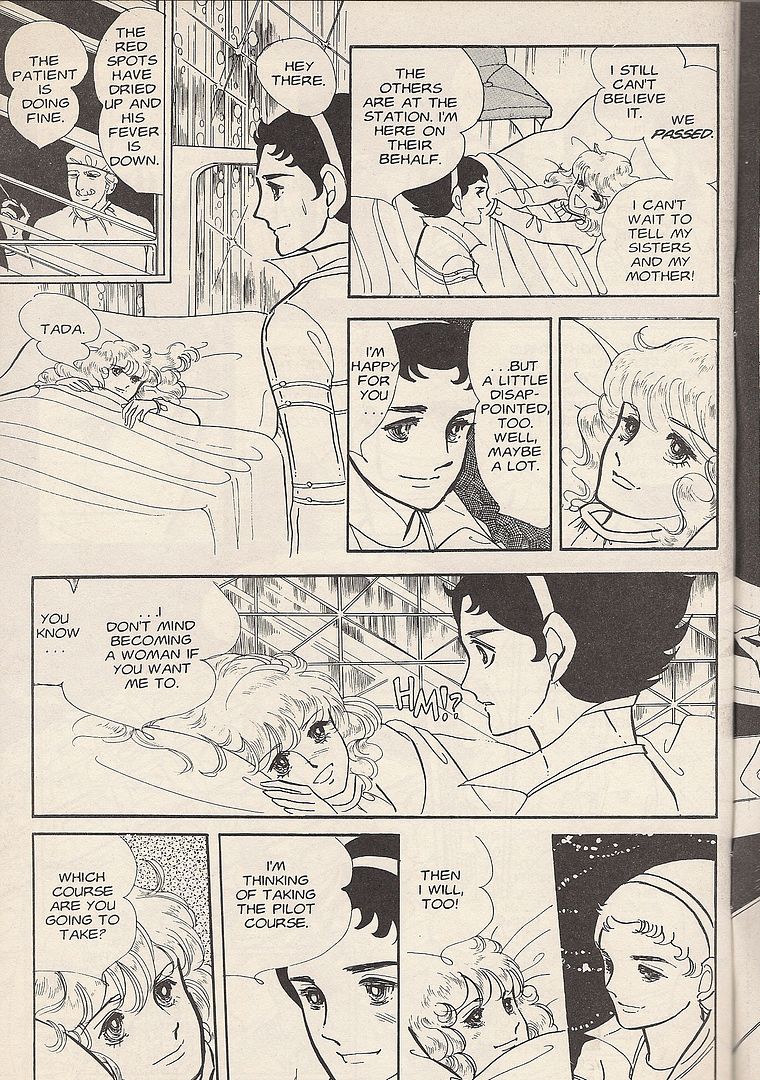

(from They Were Eleven; art by Moto Hagio)

(from They Were Eleven; art by Moto Hagio)

That leads us to something else, something only partially intended by anyone in charge, I think. Here in 2009, in North America, manga functions as a full-blown alternative mainstream of comics; not the 'real mainstream' Oni Press or AiT/Planet Lar pondered earlier this decade -- i.e. something akin to entertainments or artworks popular outside of the comics sphere -- but a 'pure comics' mainstream positioned apart from the English-language way of things, with its own set of values and tropes and genres; a setup where foreignness can be a virtue.

With a few years of that kind of development behind it, manga has become the Other. Having made its incursion on North American territory (European too, though I'll stick to what I know in person), the rhetoric surrounding manga in North American comics-focused circles is now often defined by the void manga has filled in the domestic comics scene.

Manga is comics for women.

Comics for teenagers.

Comics for homosexuals.

Comics for everyone North American comics could have reached but didn't, not in a hugely broad money-making way at least, because obviously there are some North American comics aimed at all of those groups, and women and teenagers and gays that enjoy reading North American comics, but Japanese comics brought lots of them close to the comics form and into the bookstore or onto the websites and sold them many, many things they wanted.

This isn't a zero sum game. Naturally, you can read as many comics as you damn well want; plenty of people in North America read Japanese comics and American comics and whatever UK comics that float in and poor old European comics, which have their own storied history and culture but, high-profile exceptions aside, couldn't be less popular domestically right now if they were printed on the H1N1/09 virus and had to be read with a microscope, which is still an improvement from a decade ago.

But in the commentary, the debate, the Big Picture, the mind's eye of the uncertain observer, the comic book fan who hasn't read a lot of manga, standing in the middle of a male-dominated pop comics culture - manga seems so deep, so complicated, like a foreign language somehow in English, demanding of study, aimed at a different demographic, no part-timers aloud, Your Life Required, signed in blood on the dotted line or don't even open your fucking mouth, fanboy, because you'll just get it all wrong, ducking to avoid manga swung like a club against the shortcomings and weaknesses of North American comics, despite its own troubles, its own failings, its complexities, its accidents and strokes of luck.

The overlap of Japanese and North American comics can get lost. I have no doubt that most of you reading this right now can immediately cite someone, Naoki Urasawa let's say, as a mangaka whose work isn't a million miles away from a good spread of Western comics in aesthetic approach. That's fine, very true. Japan has a bigger comics industry than ours, and some of it, as Manga-the-anthology struggled mightily to show, isn't so different in style from ours.

Yet in manga's multitudes stir popular comics that are very separate indeed, and Manga hid it all away for the early '80s, including the revolution of female artists from just a few years before, the women that set the stage for manga's reign today and inevitably swept off most early outliers, the accidental pioneers we're surveying now.

This is the closest Manga came to a segment drawn by a woman: Schizophrenia, by Yôji Fukuyama. That's because Fukuyama was good friends with shōjo manga pioneer Moto Hagio in high school.

Seriously, that's as close as we're gonna get.

On the other hand, the entry does offer a glimpse yet another breed of mangaka still obscure in English translation: the dedicated short form artist. Fukuyama has had numerous collections of short comics published in Japan, with three larger, dreamy projects translated to French and published by Casterman, the longest of them taking up two volumes. Tellingly, the only example of Fukuyama's art I can find in an English edition besides this one is his guest drawings in the French-born artist Frédéric Boilet's 2001 autobiographical romance Yukiko's Spinach (translated in 2003 by Fanfare/Ponent Mon):

Fukuyama drew the lil' angel. The lovely Japanese woman is, inevitably, Boilet's.

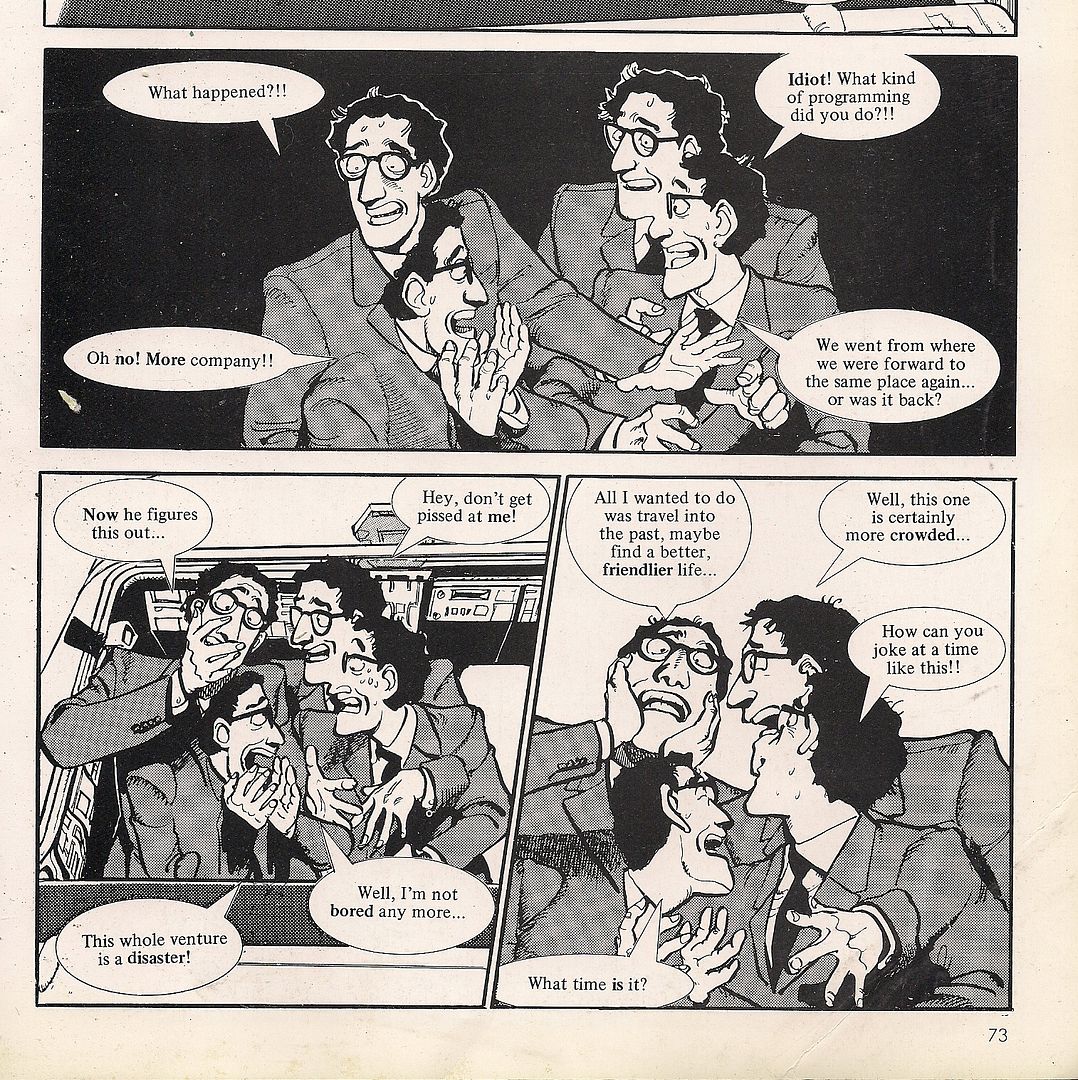

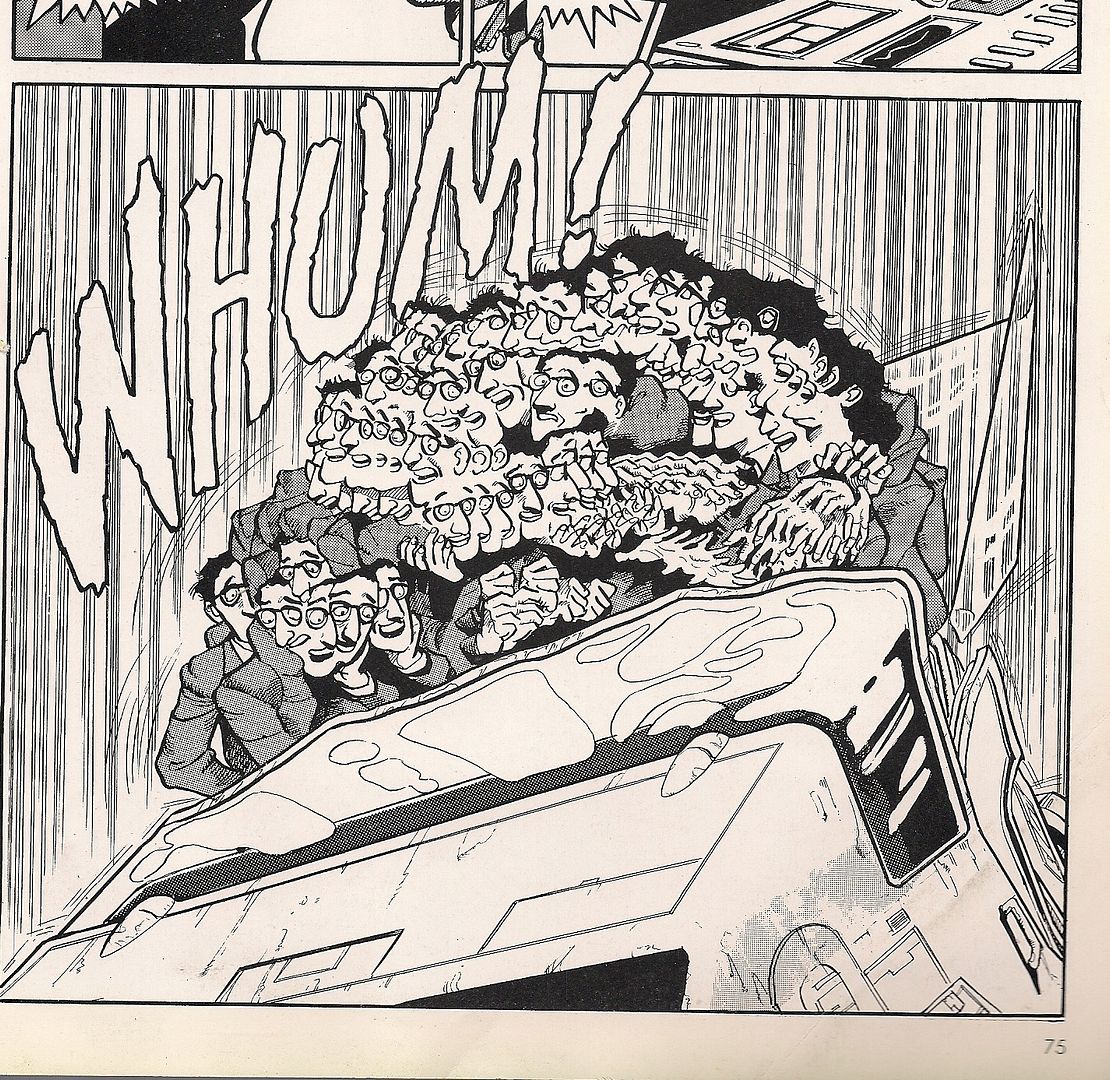

Schizophrenia, meanwhile, is a sort of philosophical sci-fi/comedy thing about a man who builds a time machine to whisk him away to the better world of the past. Unfortunately, his invention only takes him ten minutes into the past, just as he's walking into the room. The two hims then try to activate the machine again, which leaves them only seconds away from where they were before, with their bodies now (then?) fused with the bodies of two more versions of themselves. This continues until the man is a shambling, hideous mass of Him, arms and legs everywhere, at which point they all agree to stay inside and watch television.

It's a cute (and gross) fable, and oddly precognitive - the doubling motif also appears in one of Fukuyama's recent forays into a different art form, Doorbell, a short anime film he directed in 2007 for the Studio 4°C theatrical anthology project Genius Party. And like all fables, there's a helpful moral: a person can try to change their environment and thereby themself as much as they want, but it's futile. You'll always remain basically the same, if amended by fragmentation to a weird and grotesque degree.

Couldn't that be true of an art form as well? For Manga, where "[n]othing would give us greater pleasure" than to enhance the Western understanding of Japan itself, as per Executive Managing Director Ookawara on the back cover? Maybe as per the unknown desires of Editor X, whom I'll identify soon enough? I mean, we've seen plenty of art so far, but definitely nothing like this:

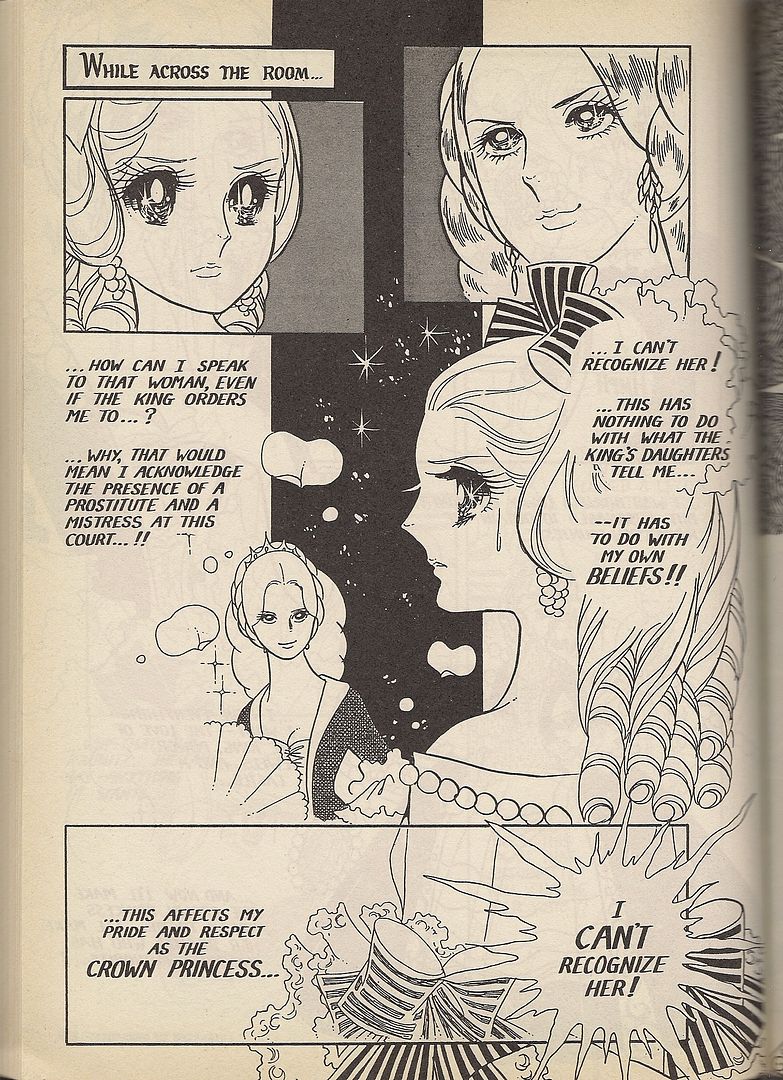

(from The Rose of Versailles, as excerpted in Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics; art by Riyoko Ikeda)

(from The Rose of Versailles, as excerpted in Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics; art by Riyoko Ikeda)

Huge, dewy eyes. Sparkles. Petals. A collage-like page construction. Big ol' close-up of a ribbon at the bottom. That's '70s shōjo manga, comics that grabbed the form by its collar and wrung it loose. It was the work of women, the Year 24 Group, named for the year many of them were born (Shōwa 24 or 1949, giving rise to an alternate North American title, the Magnificent 49ers), a wave of female artists entering the girls' comics scene and forcing its evolution from a staid, often Tezuka-derived style to a dynamic, panel-bursting thing more in line with what 'manga' looks like today on casual glance, ready and willing to accomodate experimental effects and new subject matter. And shit blowing up:

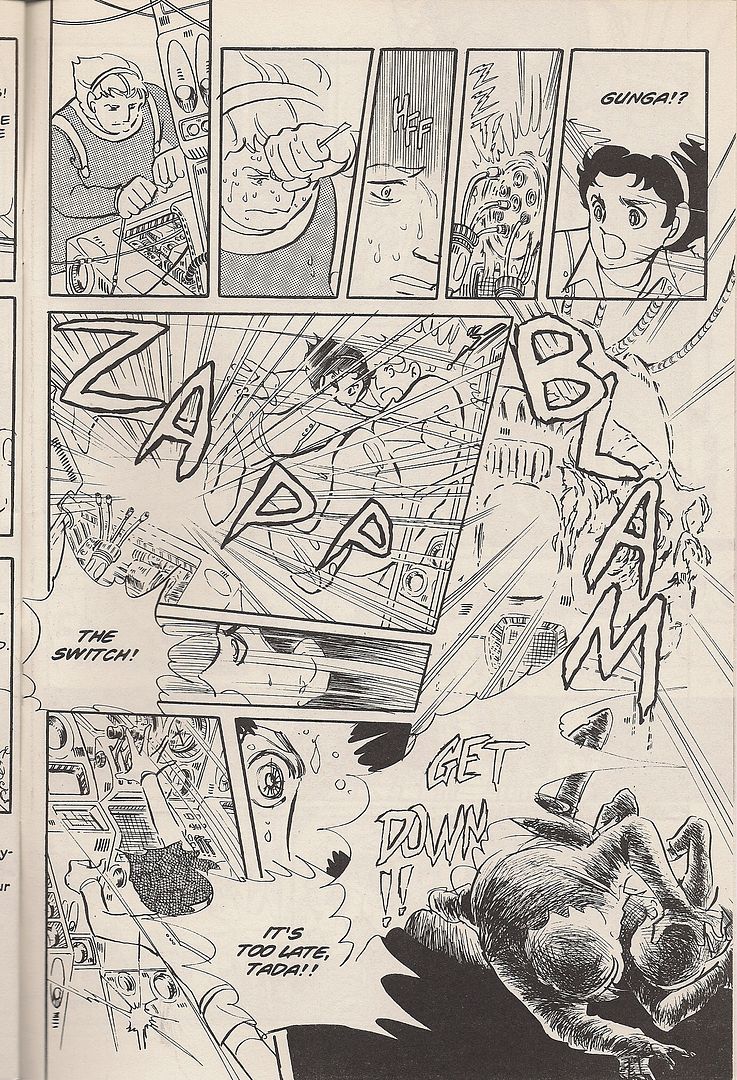

(from They Were Eleven; art by Moto Hagio)

(from They Were Eleven; art by Moto Hagio)

That's from a quintessential shōjo story of the era, Moto Hagio's They Were Eleven, published in 1975 and subsequently adapted to television, stage and screen. I'd say it's the most exciting looking image I've posted so far, and possibly the most confusing. It also looks nothing like any mid-'70s North American comic I can think of, mainstream or underground. It's totally uninhibited - not in the manner of S. Clay Wilson's seething panoramas or Jack Kirby's gesticulating figures, but in how the panel-to-panel storytelling runs screaming down the page, loud and fast so that the unseen activity in between panels registers as just as hyperactive as what's actually drawn. The character art signals its era, yes, but the narrative design is startlingly modern.

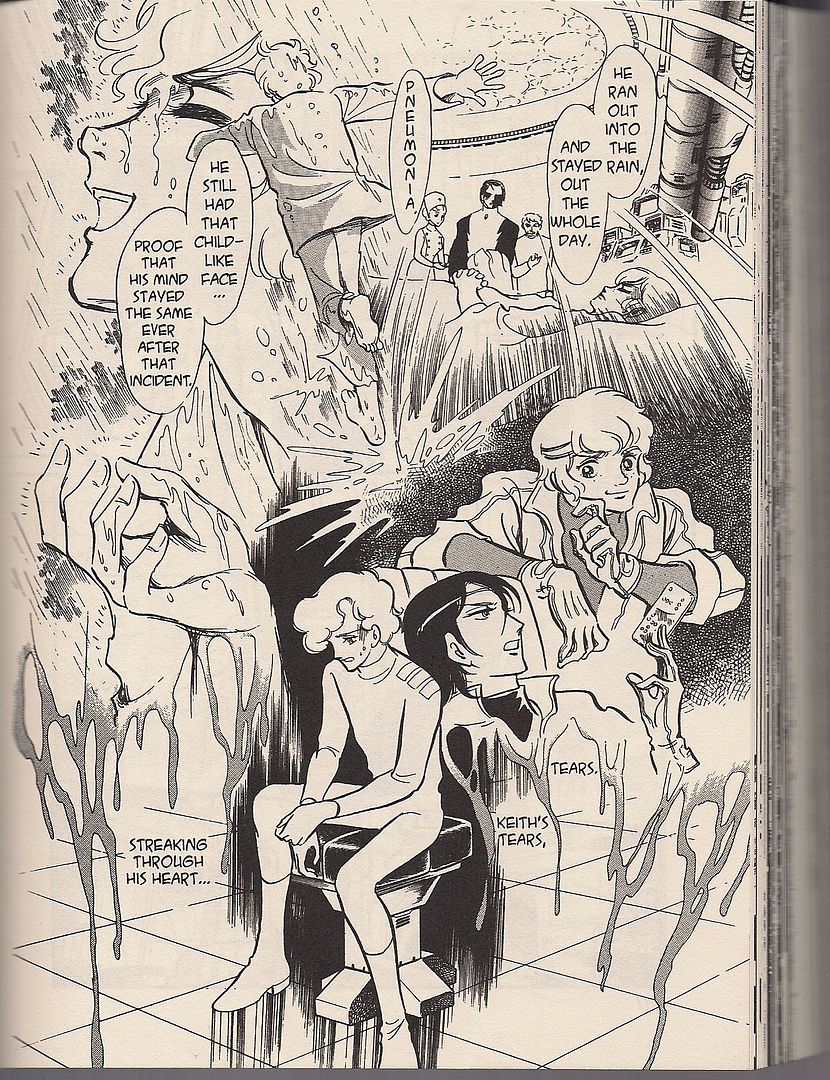

(from Toward the Terra; art by Keiko Takemiya)

(from Toward the Terra; art by Keiko Takemiya)

None of this is to downplay the efforts of male shōnen artists of the time or the alternative comics talents working in magazines like Garo or really anyone else -- the '70s are often considered a Golden Age for manga all around -- but female artists like Hagio and Riyoko Ikeda and Keiko Takemiya were working toward what amounted to a popular avant-garde, big-selling comics that pressed firmly against what 'comics' were capable of, drafting a new iconography for new layouts that married pulsing fast reading to pages that stood as self-contained expressions of their characters' psychological states while getting the story told.

And that's to say nothing of subject matter, including the mid-'70s development of shōnen-ai, "boys' love," aestheticized same-sex desire which begat the more explicit yaoi of the self-published dōjinshi scene.

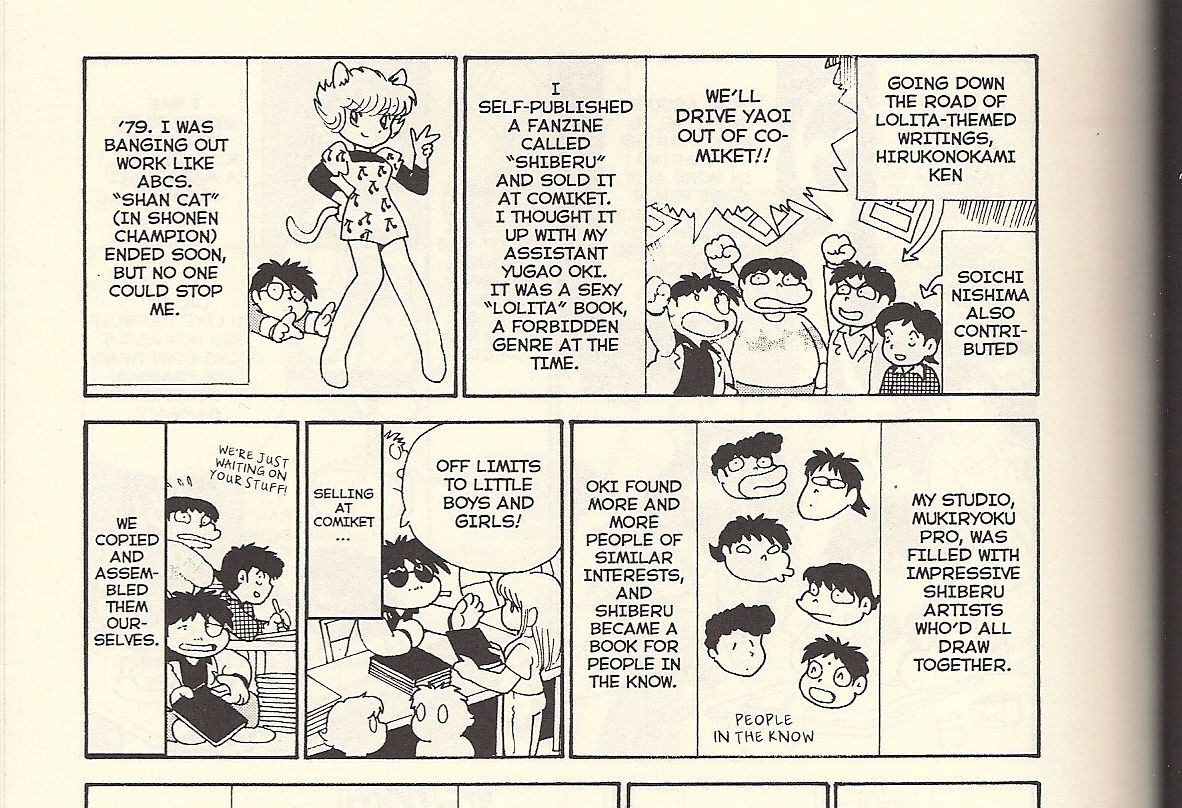

(from Disappearance Diary; art by Hideo Azuma)

(from Disappearance Diary; art by Hideo Azuma)

As you can see, the heavy female presence in fandom toward the end of the decade was not without opposition. Girls and their fanfic and their slashfic; sometimes I get the feeling that some North American funnybook readers see 'manga' (or anything that looks like it) as the Twilight of world comics due mainly to its visible female readership, or maybe just its feminine aspect, emphasized by the relative absence of women reading a wide swathe of North American comics. Which means more money for woman-targeted manga, which means more poppy shōjo on the shelves; it should be noted that josei manga, aimed at mature women, has had a harder time getting a foothold in North America.

Anyway, it's no surprise then that Manga-the-anthology put its fingers in its ears and shut its eyes to the very presence of female comics artists upon its early '80s release, to say nothing of the influential visual experiments they conducted - the prior decade had not been a Golden Age for North American comics, with the underground scene witnessing a distribution meltdown and neophyte mainstream artists expressing belief that they'd be the final generation of comic book artists. The Direct Market was still young by the time 1980 rolled around, and while woman-targeted, woman-drawn and/or woman-appealing comics existed, they were niche in the niche that comics already were, and good business perhaps suggested that they and their formal tricks were best kept obscured from a foreign anthology's window view unto Japanese culture.

Instead, we got this:

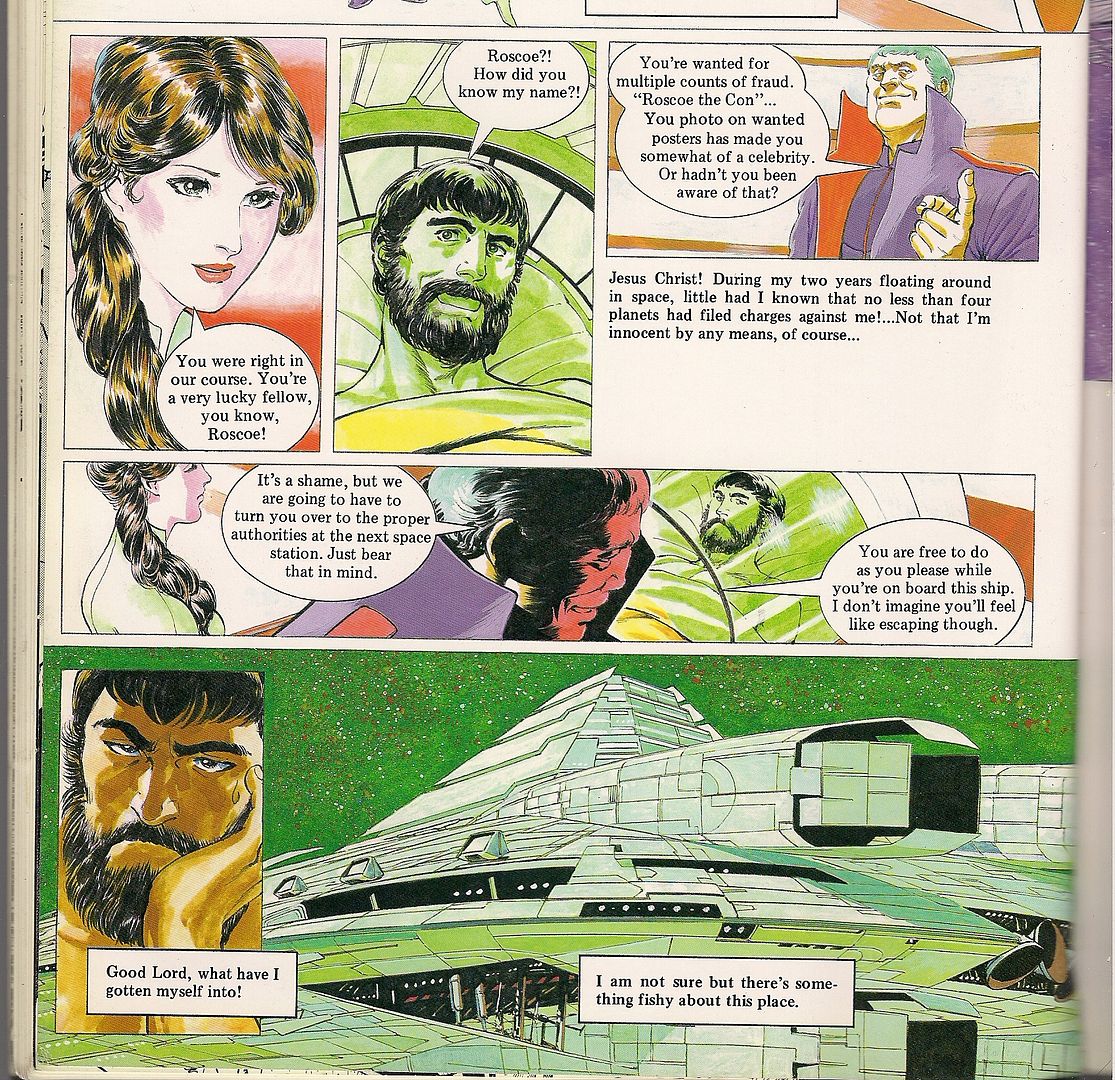

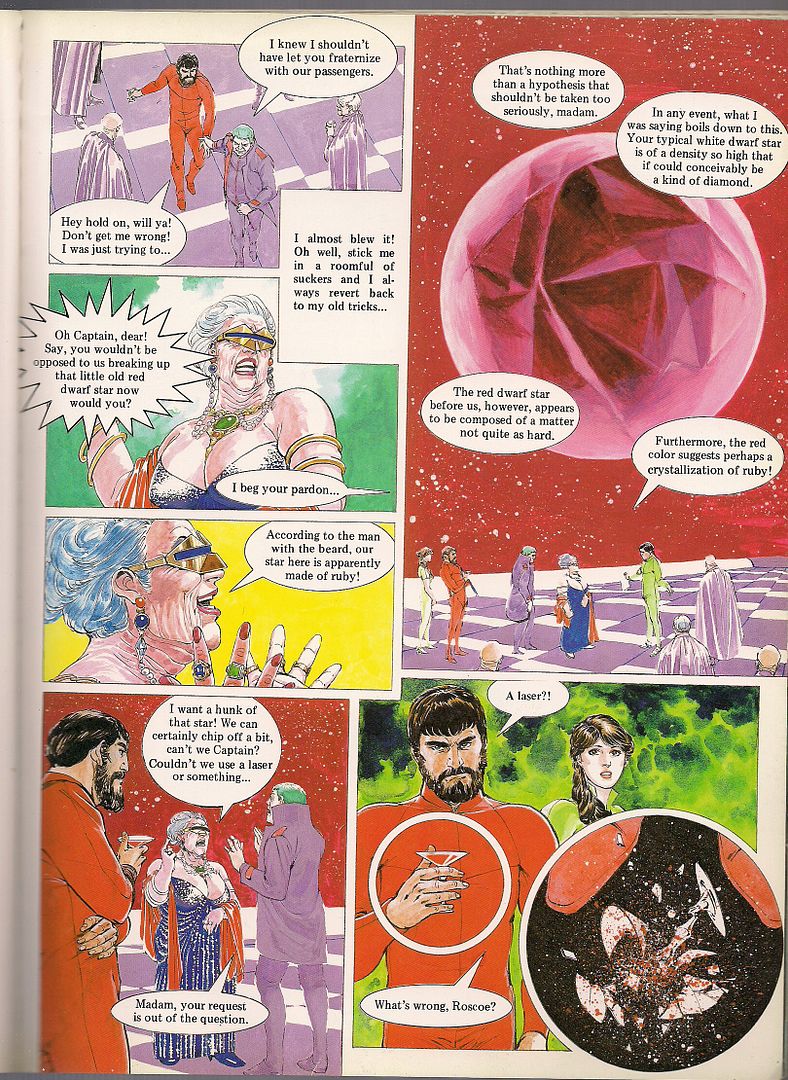

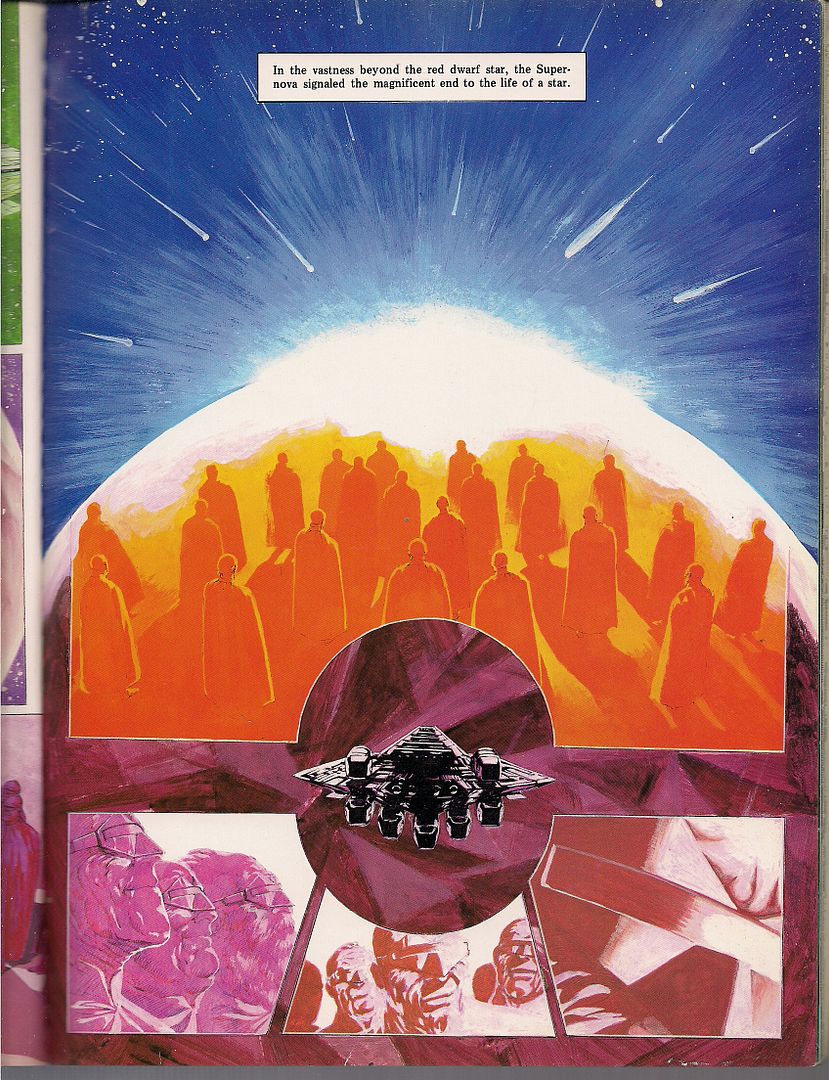

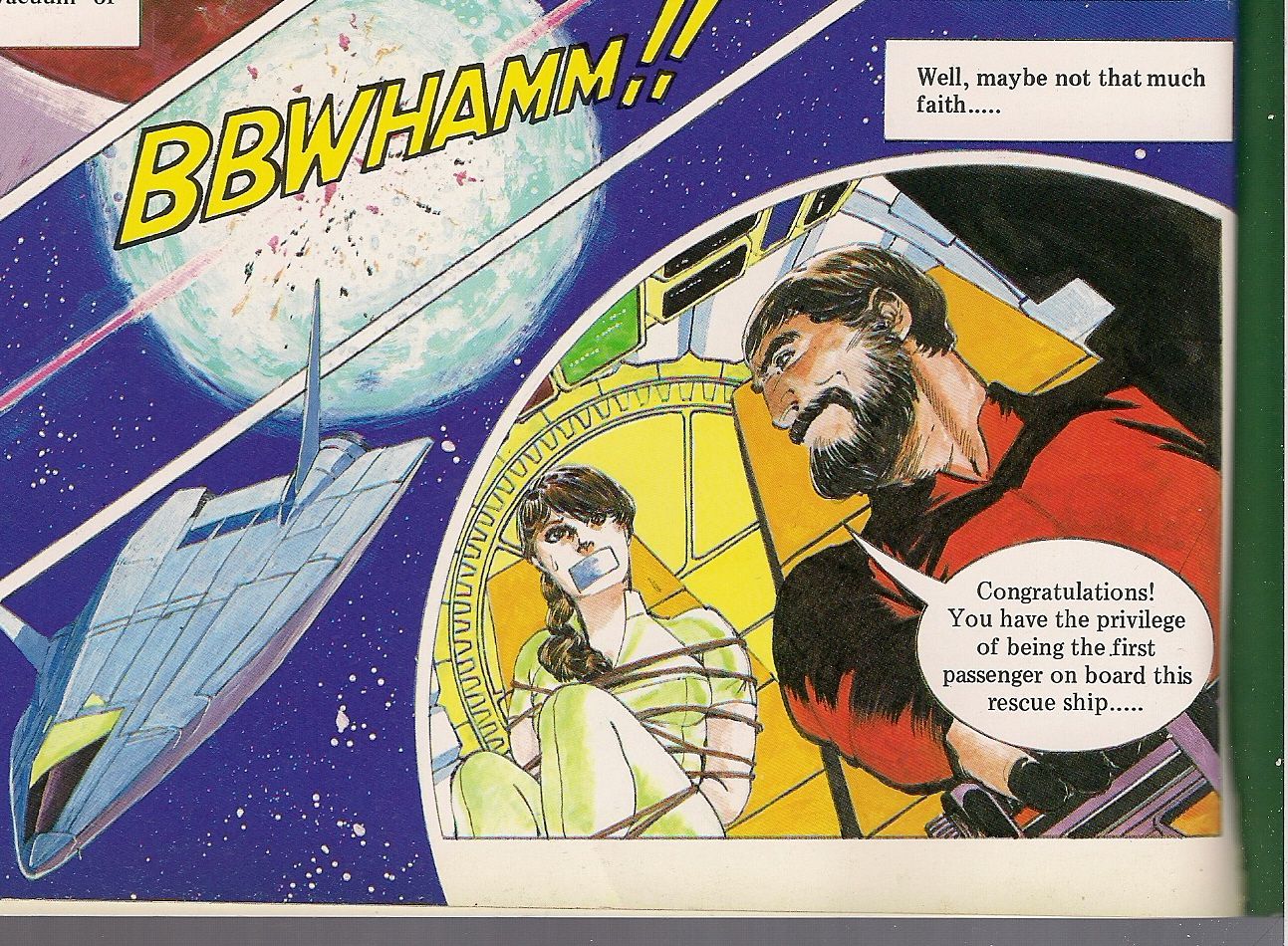

God! An old fashioned space-faring yarn with a gorgeous woman looming over a rogue adventurer and his manly facial hair while he ponders his latest tight spot! I love this vintage pulp story type of comic, and I bet artist Yukinobu Hoshino (credited as Yukinori Hoshino) loves it a hundred times more. In the tradition of fantasy-variants-on-old-stories from comics and magazines past, The Mask of the Red Dwarf Star transposes a Poe classic to the sea of stars, as con man Roscoe finds himself captive on a luxury vessel dedicated to carting rich old folks in cryogenic slumber all over the universe, thawing them out for only the rarest and most novel sights, like an imminent supernova

Hoshino draws in a stately, handsome manner; if Manga was aiming to be an irregular Heavy Metal for Japanese comics this is the entry that sells the notion completely, packed with bleeding rich color art reminiscent of Howard Chaykin's work on Cody Starbuck around the same time, but with an evident 'realist' manga approach to the character designs. There's wit along with the gloss - the story's colors are derived from the seven rooms identified in The Masque of the Red Death, with the red dwarf hanging in the void as illustrated above standing in for the red light bathing the black and final room, the chamber of death presented as icy, lifeless space.

The artist was part of a male manga generation that debuted in the mid-'70s and adopted a Western, often European approach to page design and in-panel detailing; the best known of these artists in North America is probably Akira creator Katsuhiro Otomo, and while I don't know of any direct influence of his on Hoshino's work, his time of the latter's arrival on the scene plugs him in with that faction, although Jason Thompson, in his Manga: The Complete Guide, argues that Hoshino is more in line with an older artist, infamous Crying Freeman/Sanctuary super-realist Ryoichi Ikegami, a Garo alum that blazed a Neal Adams-influenced trail through the post-gekiga/seinen Manga for Men arena for most of the 1970s, with a few memorable layovers in boys' comics like the official '70-71 Spider-Man manga.

Hoshino's visual disposition made him ideal for Manga-the-anthology, and attractive to an early manga-in-English industry that valued artists like Otomo and Ikegami for their Western approach. VIZ published Hoshino's 1984-86 hard sci-fi story suite 2001 Nights as pamphlets in 1990 and 1991, and then as three collected volumes in 1996, while presenting an abridged edition of his 1987 story collection Saber Tiger in 1991 as part of its short-lived Spectrum line of oversized softcover books of heavy-detail art, along with Natsuo Sekikawa's & Jiro Taniguchi's Hotel Harbour View (which is awesome) and Yu Kinutani's Shion: Blade of the Minstrel, (which is not awesome in the slightest, but makes for a great trivia answer).

Later, Dark Horse published Hoshino's 1993-94 manga adaptation of James P. Hogan's The Two Faces of Tomorrow as a 13-issue miniseries in 1997 and 1998, then didn't collect it until almost a decade later in 2006. By that time, Hoshino's type had almost vanished from North American manga publishing, like they were wiped out by a supernova blast as filtered through a ruby crystal into a laser beam aimed at a spacecraft, in the hoary pulp SF tradition.

Hoshino remains active in manga today; he just won an Excellence Prize at the Japan Media Arts Festival last year for his episodic 'manly professor of folklore solves mysteries, maintains mustache' series Munakata Kyōju Ikōroku (Case Records of Professor Munakata), ongoing in some form since 1995, anticipating the release of a twelfth collected volume next month, and currently enjoying its own exhibition at the British Museum until January 3, 2010.

We may yet see more of him in English, though his type of comic doesn't make the kind of money from the target audiences that 'manga' as a live concept embodies these days. You look at his art and it's pretty and skilled, but it embodies the spirit of a dashing space cowboy zipping out of danger with a freshly-rescued hottie at his side, still bound and gagged, regarded with a friendly enough leer.

Aw, don't sweat it babe. He'll cut you loose when he knows you're ready.

IV. WE'RE ALL JUST ANIMALS

And speak of the devil: Katsuhiro Otomo!

Yep, the man himself is among the Manga artists, his entry probably composed while he was working on Domu: A Child's Dream, the esper action epic that honed his skills for the Akira project. Otomo was actually a prolific creator of short, often experimental comics prior to that, though this large body of work is nearly unknown in North America. I can only think of the 1992 Epic one-shot Memories, which presented a short story later adapted to theatrical anime form in a 1995 anthology of the same title (though a 1995 Random House Australia release also titled Memories boasts over 200 pages of Otomo shorts in English for those willing to hunt and pay).

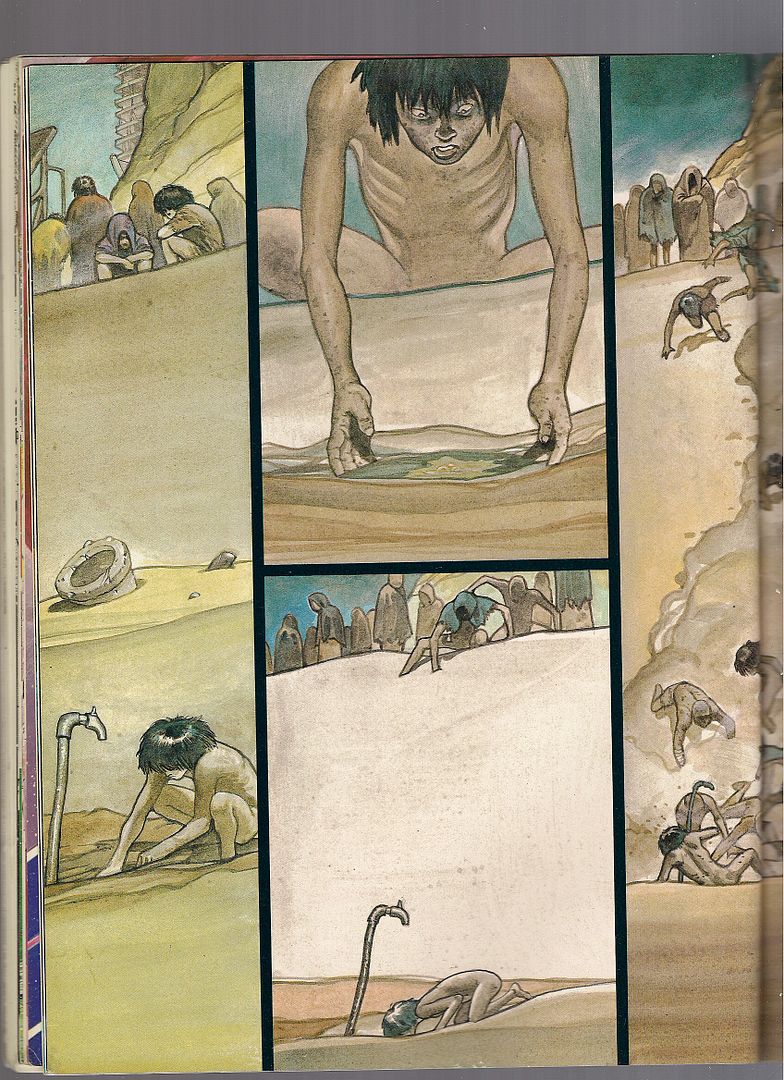

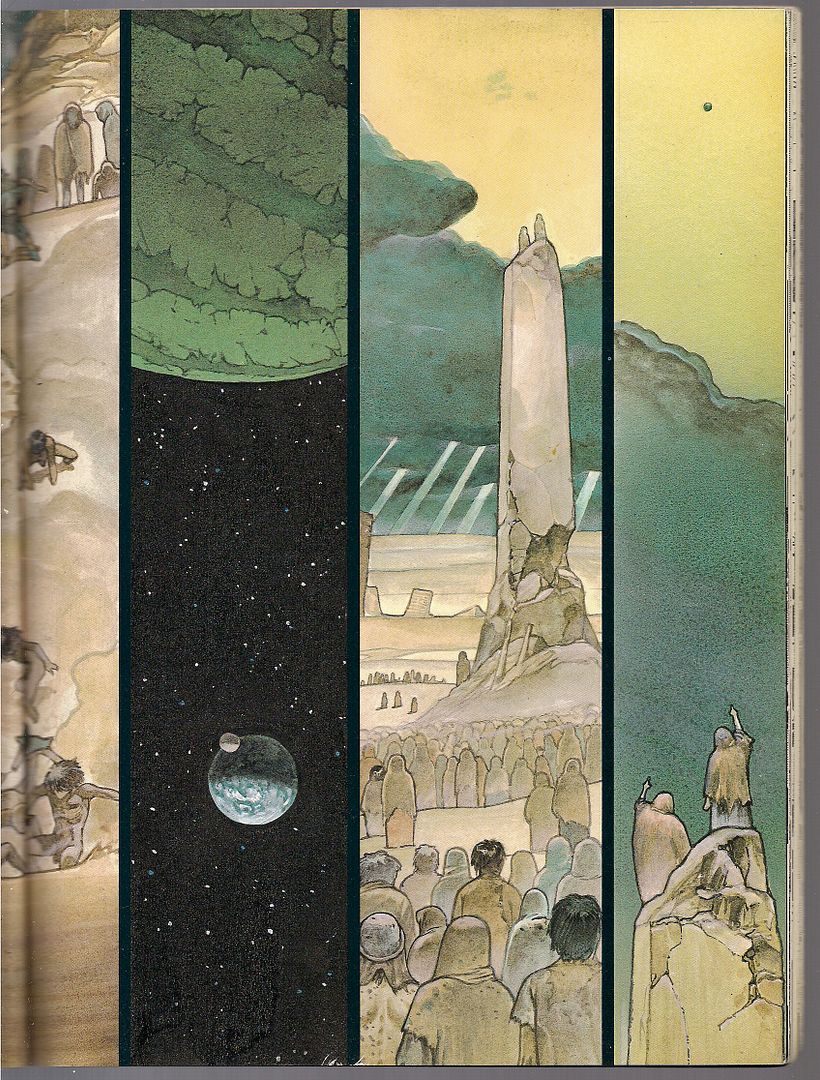

The Watermelon Messiah makes for a tricky-cute seven pages, similar in outlook to Otomo's opening to the anime anthology picture Robot Carnival from 1987, in which the film's title -- literally a clattering, smoking, gigantic ROBOT CARNIVAL -- goes parading through a hapless village and wrecks the place with entertainment or just the promise of such. It's a first world story, anxious about progress at a time where Japan in particular seemed primed to take on the world.

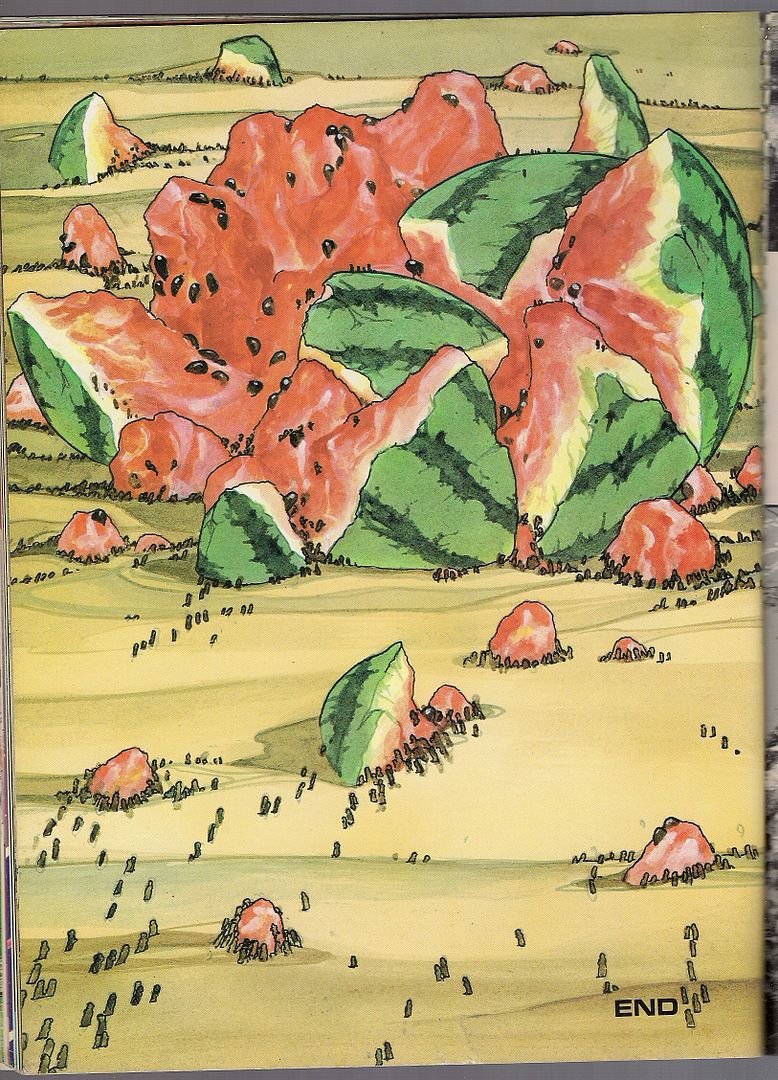

Otomo's story in Manga is more about unity, but just as downbeat: in a series of long vertical panels, a gigantic watermelon zooms through space toward a ruined, ragged civilization of scavengers among fallen skyscrapers. The space melon strikes the ground and splits apart, and a final splash depicts tiny people crawling all over it like ants.

Stripped of our technology, our progress (and our comics industries, no doubt), we're tiny and similar in our helplessness, every color and creed as pathetic as the next under the eye of an uncaring god, to flaunt a Western idea. Japanese comics - taste the sensation!

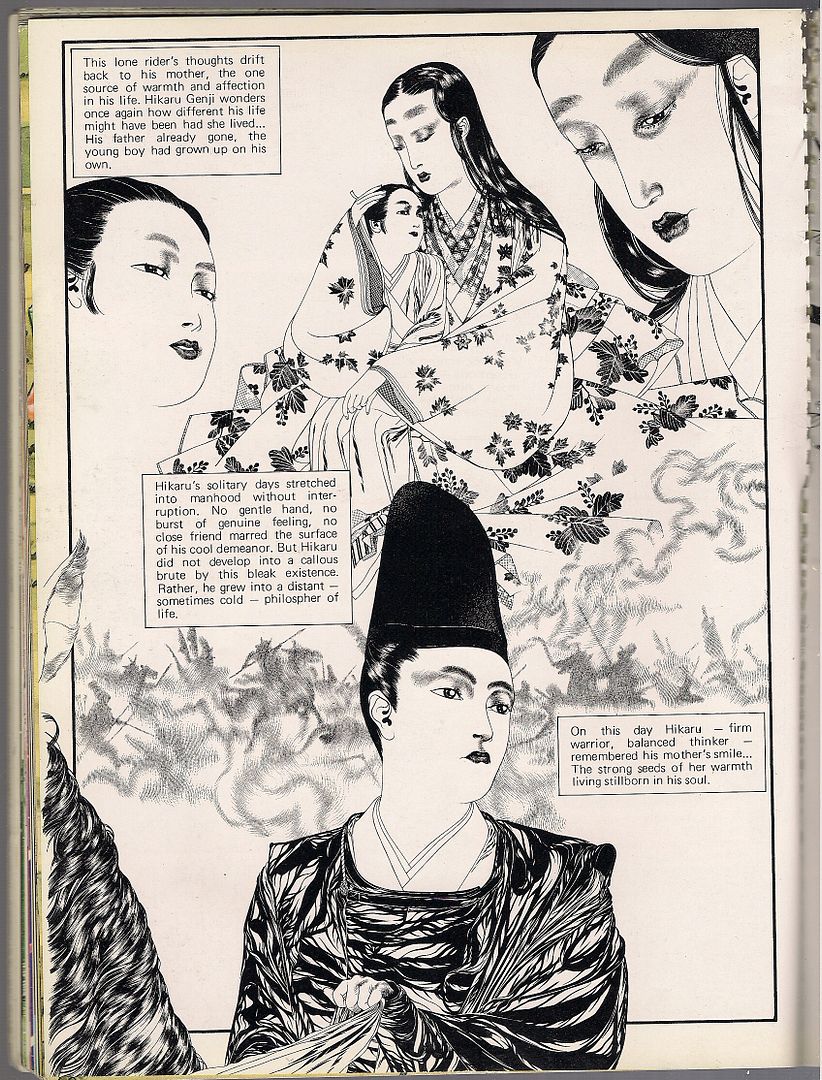

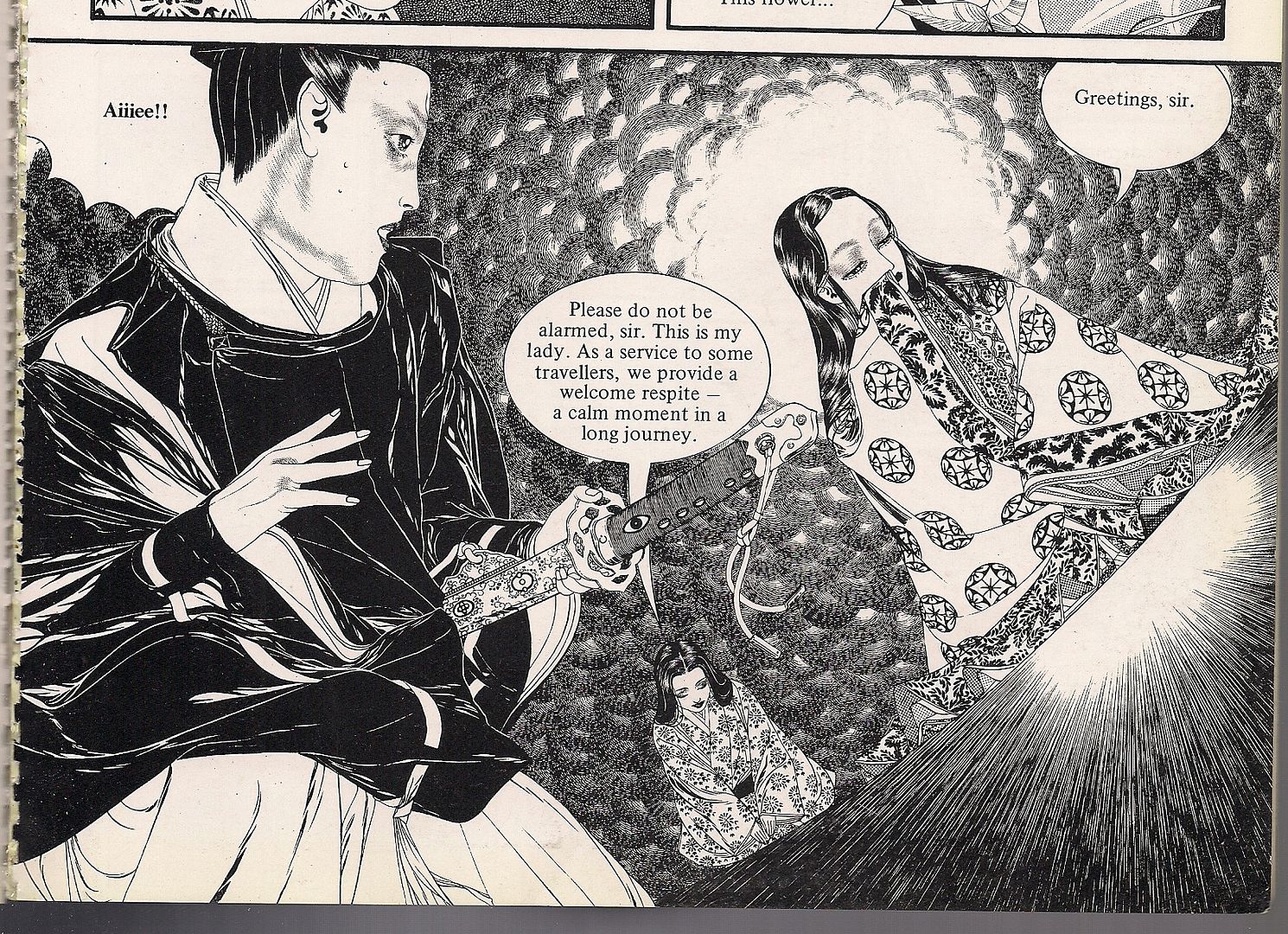

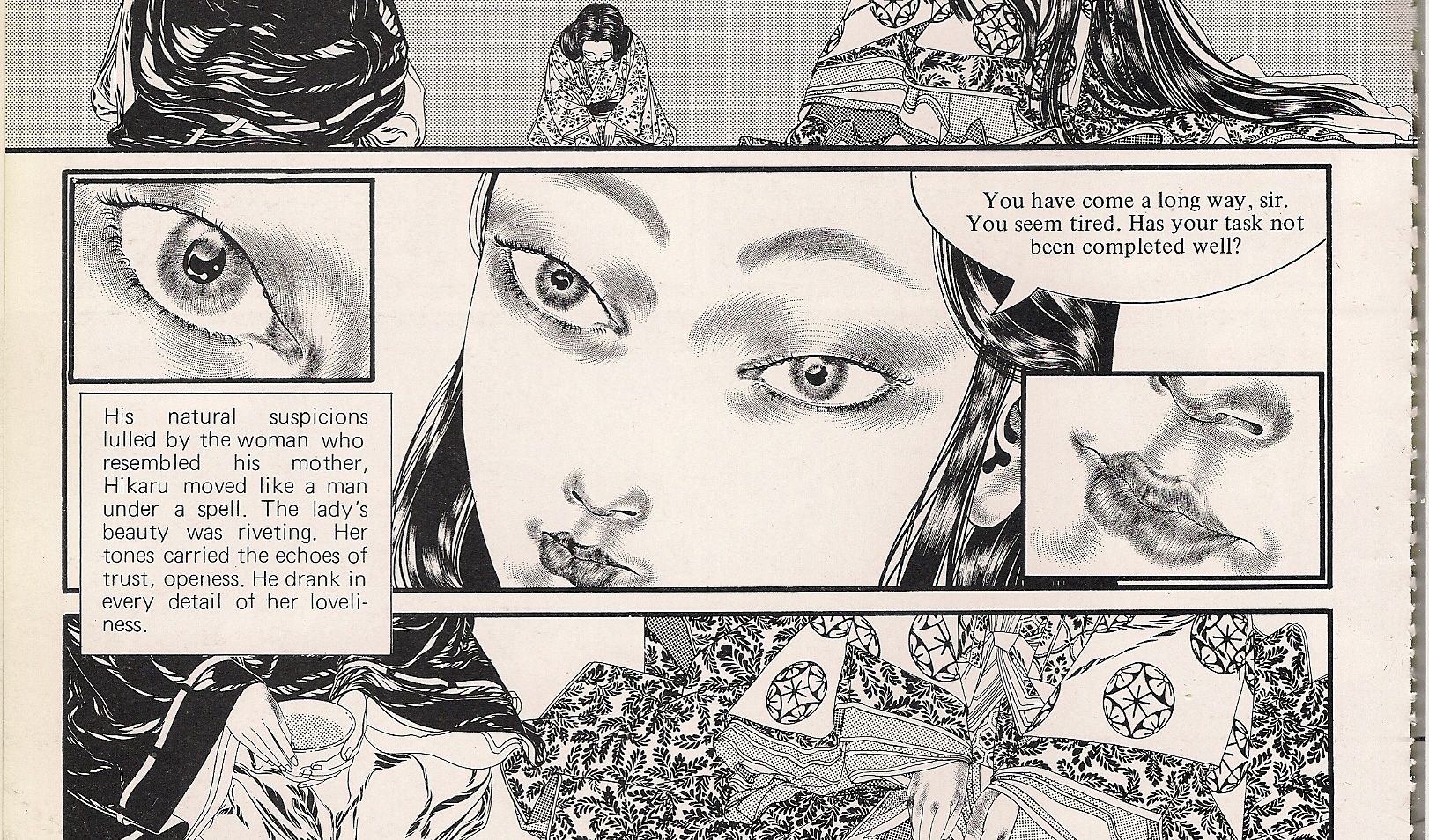

Here's another trick, a story titled Midsummer Night's Dream, conceived and drawn by Keizo Miyanishi and written in English by Lee Marrs, the project's lone female participant and the only Westerner granted a story credit above the expected English adaptation work. The plot is simple: Hikaru Genji, ice-cold negotiator with a most literary name, stops to admire a Yugao flower while on a journey and finds himself duly confronted with the splitting image of his beloved dead mother, accompanied by a beautiful Lady. Genji hits it off well with the Lady, but their night of passion ends with her disappearance: ah, the women were just spirits in disguise, playing a trick so as to unlock Genji's sensual warmth for his own good! Captions assure us he later hooks up with a neighbor's daughter. THE END.

The allusions to Shakespeare and Lady Murasaki are obvious. Mono no aware is absent, replaced by an 'in praise of love' outlook that seems to apply the English drama's faerie-tamper'd romance as a salve to the crueler fates witnessed in The Tale of Genji, where "Yugao" was a perfectly human woman who died from her own encounter with a spirit, sent by another lover of Genji, the Shining Prince.

You can catch some approximation of that Heian beauty in Miyanishi's character art, which seems mildly evocative of Yamato-e narrative painting, a tradition dating back to Murasaki's era. Thus, the primacy of the Japanese half of this mash-up rests in the visual aspect, undercut by Marrs' Western dramatic citations in her story. It doesn't add up to a lot as a comic -- 'Genji as a short story with a happy ending' sounds a bit like a joke about an American version of the tale -- but its give-and-take between literary traditions mirrors some of the struggle between English and Japanese-based comics traditions going on inside the Manga project.

And isn't it striking that we've got another departure from the North American comic style here - once again, as it was with Hiroshi Hirata's work, given an apparent pass by the exotic, easily-identifiable look of the work?

The trick is, Miyanishi's classicism isn't mainstream in manga at all. He's actually an alternative cartoonist, far more underground than anyone else in the book, slated to appear again in English soon as part of Top Shelf's Ax: A Collection of Alternative Manga. But even around the time of Manga, he more prone to images like this, from a 1979 book cover:

He wasn't a prolific alternative cartoonist, however (although Midsummer Night's Dream did later show up in a 1990 collection of his short stories); he seems frankly better known online as mastermind behind the music act Onna, accompanied by images like:

But if you look close at his Manga disguise, you can see untoward detail about the eyes and lips. A Renée French fuzz. A lust beckoning undirected release from tradition. This can go several ways.

There's an issue that crops up sometimes in discussions of manga: whether 'manga' is really 'comics.' Some think not! As you can tell from my free usage of 'manga' and 'Japanese comics' and 'funnybooks' and the like, I'm naturally disposed to thinking otherwise. They're all words and pictures, right? Like how people are all the same, breathing the same air, bleeding the same blood. All ants, all specks, when you pull back enough. Fragile creatures; who has the time for conflict?

Why drive wedges between us? I was raised Catholic, so that's the kind of nerd I am. You can't go in with a lot of preconceptions though, if you want it to work. You can't think of 'comics' as 32-page floppy books in color. Or anything beholden to genre. You must accept that writers don't have to be in charge, that the whole idea of a "comic book writer" might be an anomaly, a sub-specialty in an art-driven storytelling. It doesn't have to be that way, it never has to be; values will compete, opinions may vary, but comics never have to be limited. Anyone of any age can read comics; any subject matter can be approached. You don't even need storytelling, because comics hide a 'fine' art aspect, a gallery art relationship in spite of or energized by its history of mass production, not that comics even need to be mass produced.

Does manga stand for all that? No, god no, but to stand that far from particulars is at heart to prepare yourself to know comics from any angle, to delve with the eye for permutation, energies old, slow or new in a whole cosmos.

God help me, the further I go the less I'm comfortable with that. Sometimes I think maybe manga isn't comics. Moreover, it shouldn't be.

What is comics? What's your history with comics? Should comics exist in the world? If so, as works of art, they have some cultural force, muted or smothered as it may be. Inevitably, this force will be specific to the culture, even if the signal is so weak it only covers the culture of comics publishing.

When the book titled Manga entered the culture of North American comics publishing, it was not in a form representative of the words & pictures called manga. Instead, intentionally or not, it matched the culture of North American comics in the early '80s as best it could: a magazine-sized, Heavy Metal-looking publication full of richly detailed art, sometimes of an authentic but stereotypically "Japanese" flavor. No formal advancement was present beyond what was known to North America. No demographic were pursued beyond the cultural norm. Manga was comics then, because it accepted the terms of the culture.

To call manga 'comics' today, don't we impliedly accept those terms again? Maybe we want to, but let's say we don't - is it wise for a North American comics reader to accept manga as 'comics,' when the terminology suggests the former can only become part of the latter, melding an insurgent popular mainstream into a smaller, older one in a way that flatters received wisdom? I'm talking semiotics here. Manga as manga has a strength that manga as just comics doesn't; in rejecting the aesthetic terms of comics, in suggesting 'comics' become more like 'manga,' don't we preserve and emphasize the progressive aspects of the Japanese form for better, deeper comparison, now that manga has gained the capitalist muscle around here to take a few swings?

Doesn't conflict make things stronger?

The burden there, I think, is not to excerpt so much. I've been going on and on about popular comics and popular manga, but what of the virtue of unpopular things?

In the macro sense, you can view comics as among the least popular iterations of North American pop culture, which arguably puts it in a unique position to offer cultural resistance. Certainly U.S. comics don't export like U.S. film or U.S. television, or fast food or soft drinks; indeed, a symptom of comics' stature is that manga has managed to build its presence as much as it has. Can you imagine Japanese pop music holding an equivalent position in the United States of America? Part of the thrill I get from comics is that it seems so pliable right now, so rich with potential. So under-studied, so unburdened with financial expectation yet so fucking young!

It'd be a mistake to overstate manga's influence in Japanese culture -- there's plenty of trouble in the air with declining circulation and competing forms of entertainment, stretchy pirates notwithstanding -- but it's plain that manga enjoys an enhanced status as a mass entertainment medium. And, as happens with mass media, money has gone in and formulae have gotten tight; the big circulation youth comics have become very editorially guided, their ingredients laid out in order as law, at least when not subject to the whims of reader response surveys maximizing consumer satisfaction.

It's said that there's little in the way of an 'art' comics scene in Japan, though the sheer size of the industry and the breadth of its history assures that Western readers won't be left hungry too soon, if the publishers remain willing and viable. Even then, manga artists seem distinctly less taken with the specifics of the comics form, instead focusing on tone or sensation or shock or drawing; use of the form as a mechanism. The closest I've seen a mangaka get to Asterios Polyp is Shintaro Kago, and his formalist mindfuck comics are both an awesomely extended sick joke and only part of his oeurve anyway.

There always seems to be less fretting about manga in manga, and I wonder if that isn't due to the comparatively smooth evolution it's had across the 20th century; PTA struggles and a lack of highbrow respect, sure, but nothing like the Comics Code Authority or the industry crash of the mid-'90s. Could it be that manga as an industry isn't as hungry for validation as comics, that artists may be hungry but must be content with remaining sort of small, while comics is small enough that the idea of 'literary' comics has materialized prominently in our midst? Is manga the better pop comics? It it best as only pop comics? Can I really say a single worthwhile goddamned thing about a popular culture inaccessible to most of us and in a language I can't even read, half-visible in translation financed by the gaps it fills in my pop culture's shortcomings and soured, biased in that way?

Gah! Catholic angst at its best! Give me something to pluck from the comics cosmos! Some worl manga insight! Just tell me something about my life, funnies! Harrow my soul! Prepare me for death!

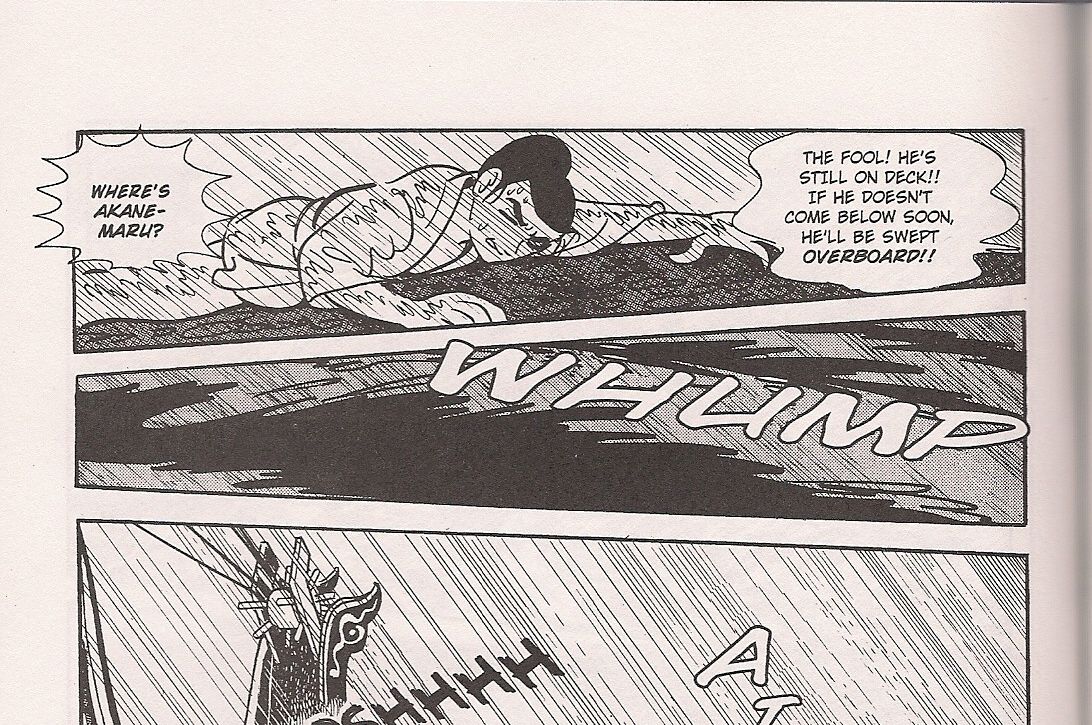

It's a march, the perception that is manga in North America. Manga-the-anthology wasn't adept enough to reproduce and it probably didn't influence much of anything, but the conditions it existed in remained present as manga slowly grew. The big three manga publisher Shogakukan shelled out the money to form Viz Media in 1986, teaming with Eclipse Comics the next year to release manga pamphlets: Sanpei Shirato's ninja comic The Legend of Kamui; Kazuya Kudo's & Ryoichi Ikegami's mutant power-like esper serial Mai the Psychic Girl; and Kaoru Shintani's jet fighter action series Area 88, which was actually very much cartooned.

Within, without. The same year Viz was established Canadian-born writer and cartoonist Toren Smith -- who had helped coordinate the Eclipse deal and worked on some of the publisher's early English adaptations -- formed Studio Proteus, a freestanding entity that would acquire licenses from Japan with the approval of a North American comics publisher (usually Dark Horse, as it would pan out) and provide flipped (left-to-right), translated comics for distribution. It'd be totally wrong to say that Studio Proteus only worked on bloody sci-fi and action comics, but I don't think it's off the mark to say that those Katsuhiro Otomo and Masamune Shirow and Hiroaki Samura releases are well-remembered by readers of my age.

All the while, there was anime, which should not be underestimated as a force in drawing eyes toward manga. It's funny that Japan's animation industry is so male-dominated and increasingly focused on milking every last drop of money out of its harder-than-hardcore otaku base, because anime in the U.S. became an open thing as VHS tapes gave way to Sailor Moon airing on television in the mid-'90s, slowly building more of an audience of girls and women that later bought the Sailor Moon manga from Mixx, which later became Tokyopop, which personified the unflipped, digest paperback manga that made history when the bookstores picked it up.

Every bit of that -- manga for girls, direct-to-bookshelves, right-to-left -- had been tried earlier. But as the 21st century crept forward, manga assumed its new identity, and the old experiments and comic book-friendly standbys didn't always find a place. They were as much manga as anything else, but what manga is had to change.

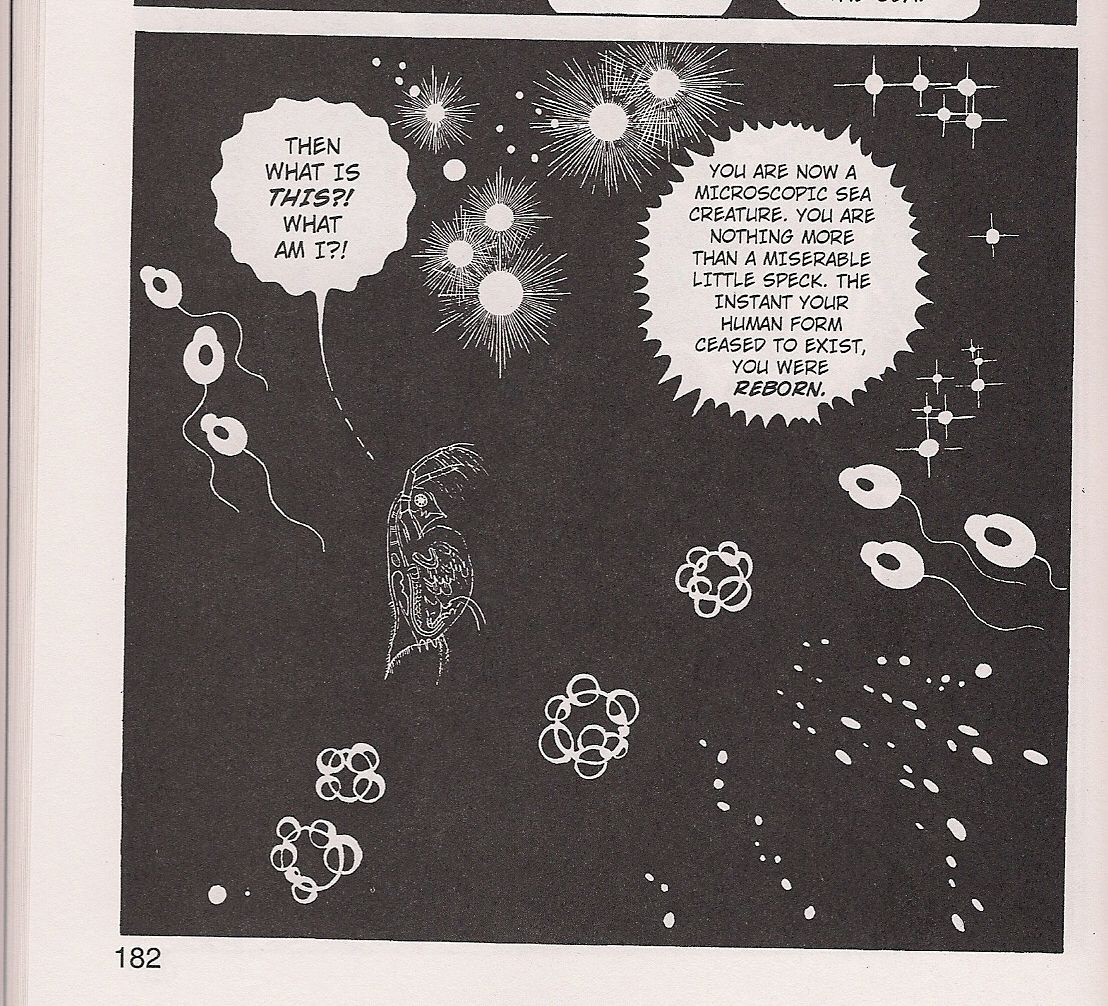

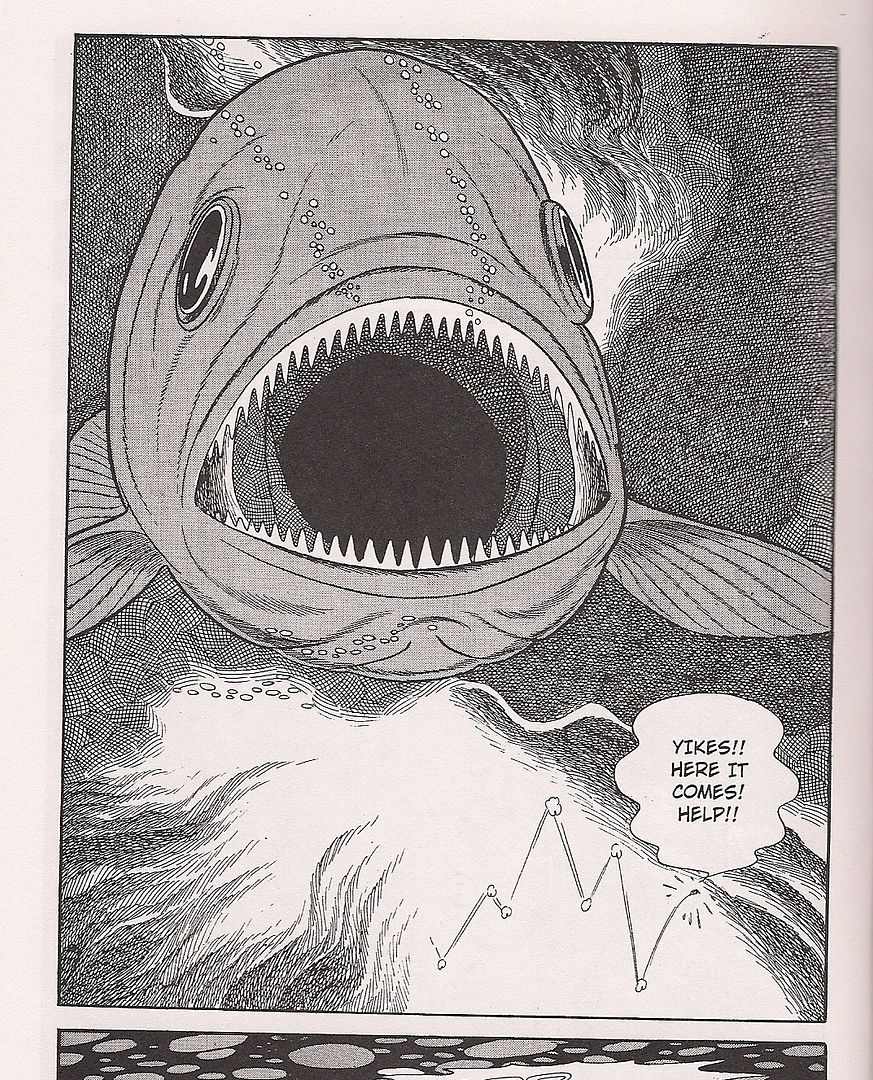

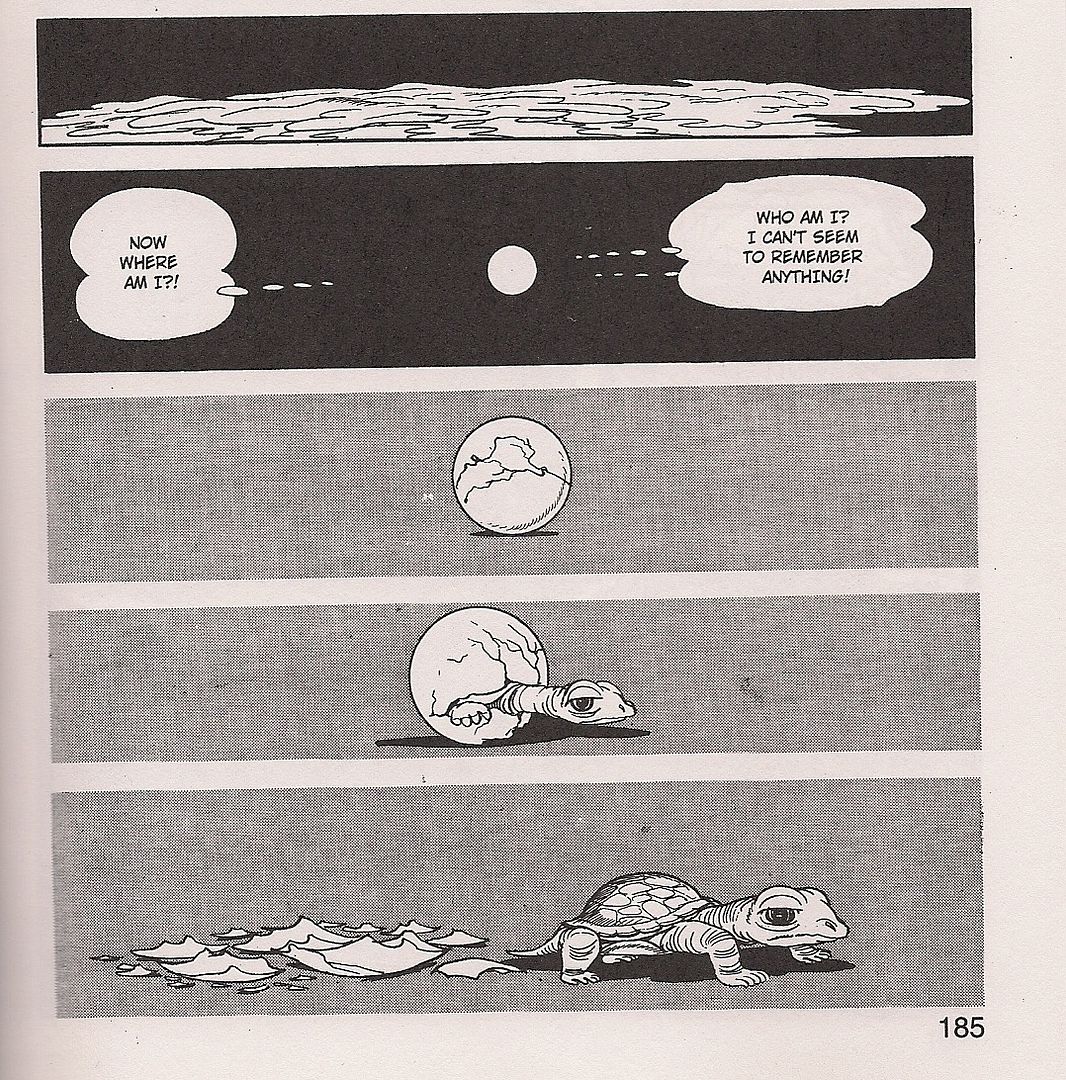

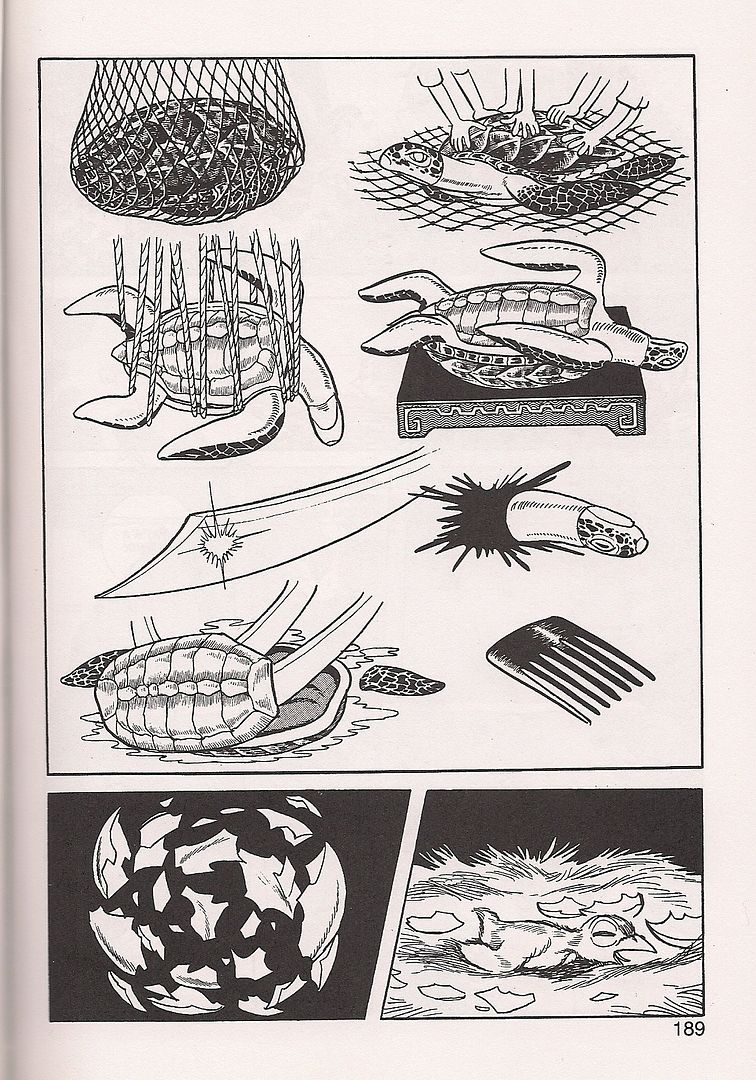

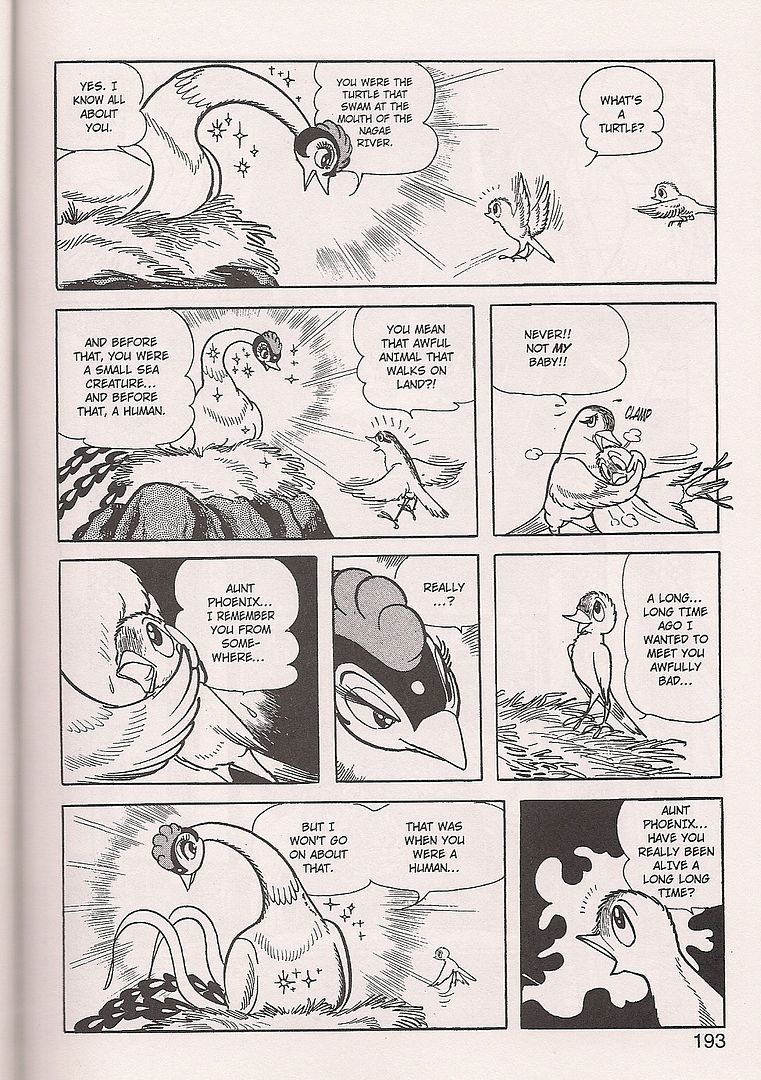

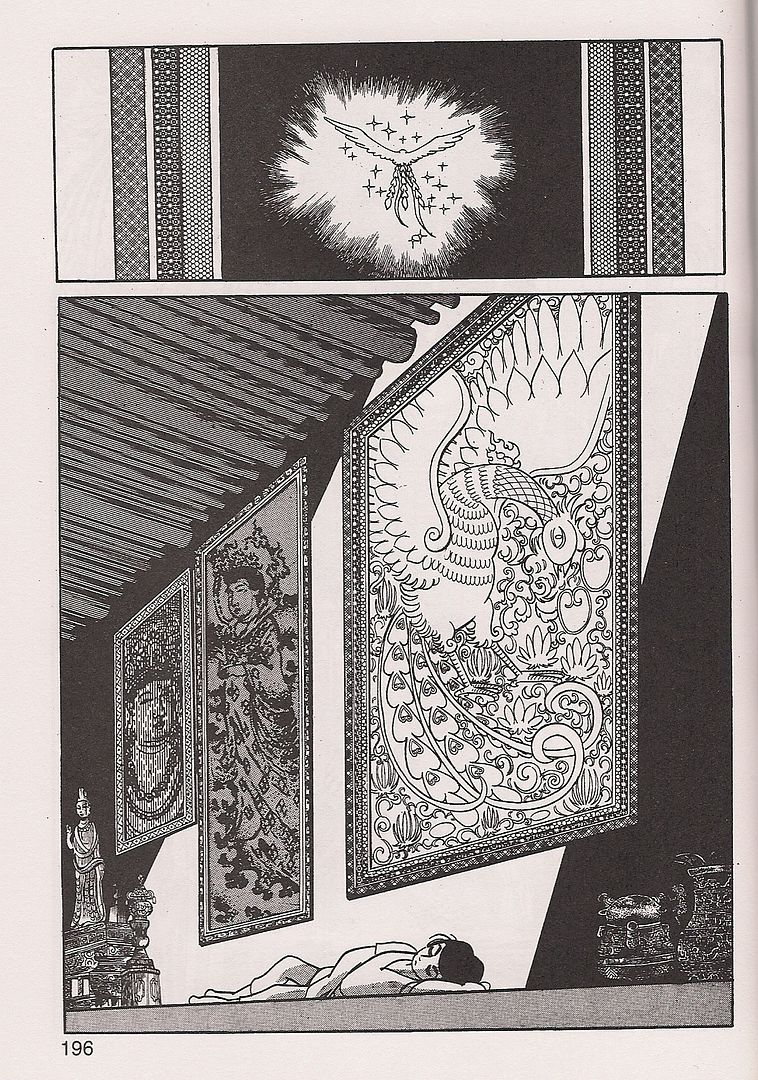

(prior seven images from Phoenix: Karma; art by Osamu Tezuka)

(prior seven images from Phoenix: Karma; art by Osamu Tezuka)

Let me tell you now about the editor of Manga: Masaichi Mukaide, the first mangaka published in English in the Direct Market era.

V. I WAS BORN, BUT...

You'll remember that Mike Friedrich served as Manga's consulting editor. Friedrich's pamphlet-format anthology series Star*Reach, launched in 1974, was a noteworthy 'bridge' comic between the underground stylings of that just-passing era and the genre-hungry territory of a mainstream still hobbled by content restrictions. They called 'em "Ground Level Comics" back then, playing on under-aboveground terminology and presenting themselves as stop #1 in the new comics future.

In his publisher's note at the top of Star*Reach #7, released in 1977, Friedrich highlighted the international flavor of the issue, including a contribution by two talents from Japan: writer Satoshi Hirota and artist "Mukaide," only one word. This was one year prior to the initial English-language release of portions of Keiji Nakazawa's Hiroshima bombing-themed serial Barefoot Gen, leaving only made-in-the-USA oddities like 1931's The Four Immigrants Manga known to me before it. I will admit, however, that the story Hirota & Mukaide created -- The Bushi, six pages -- may not have been published prior to its Star*Reach appearance.

As you can see, Mukaide drew the piece in a very American-looking style, giving me the impression that he might have been a dōjinshi artist or small press guy aiming to break in with U.S. comic books. I can find no record of any Japanese-only comics he drew, nor can I find the slightest mention of writer Hirota working in comics or manga anywhere again. Friedrich is credited with "additional dialogue," hinting that he might have eased the script into English, if that was the language it was initially written in - no translation credit is given.

Hopefully some answers will turn up in a letters column somewhere since Mukaide became a minor fixture in Friedrich's comics at the end of the '70s, illustrating stories for the aforementioned Lee Marrs and Steven Grant in issues #15 and #18 of Star*Reach, and showing up in half the six-issue run of sister series Imagine (#3, #4 and #6), working again with Marrs in issue #4 but writing his own work otherwise.

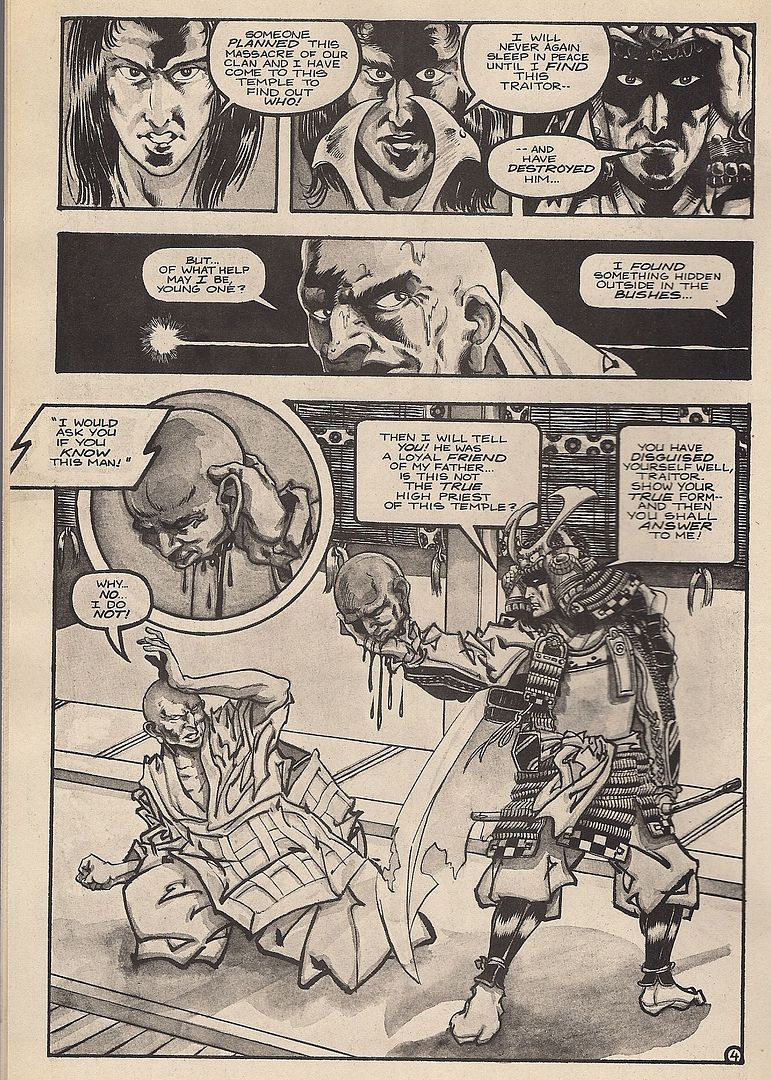

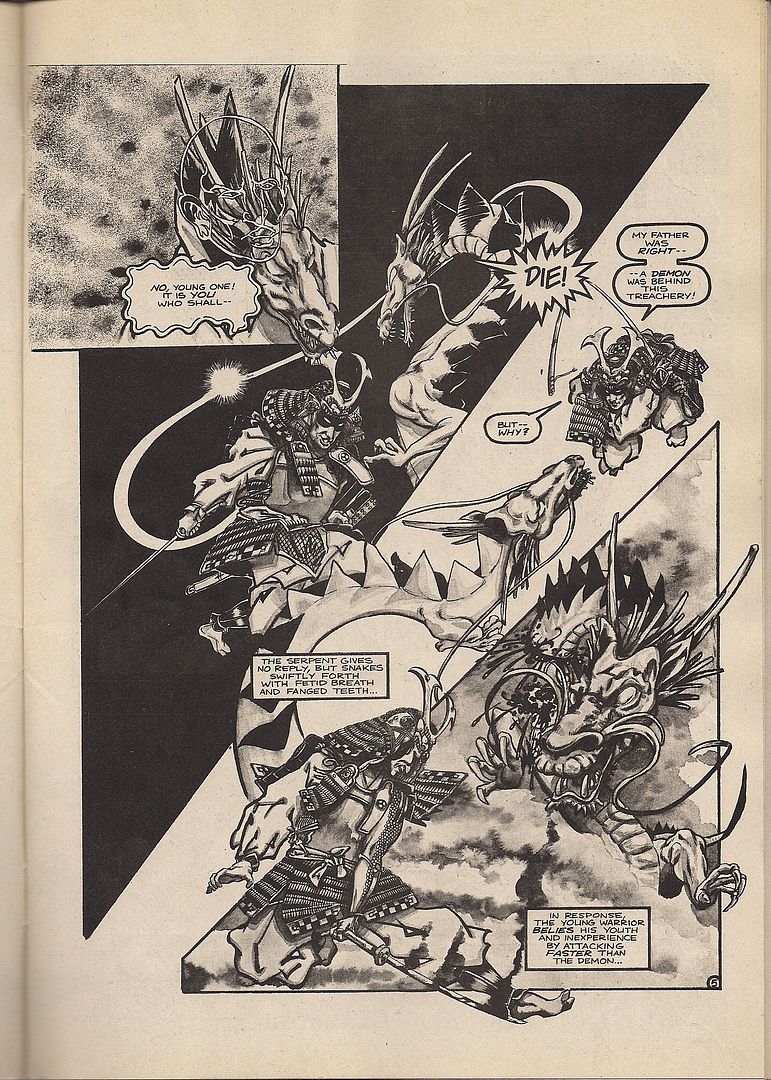

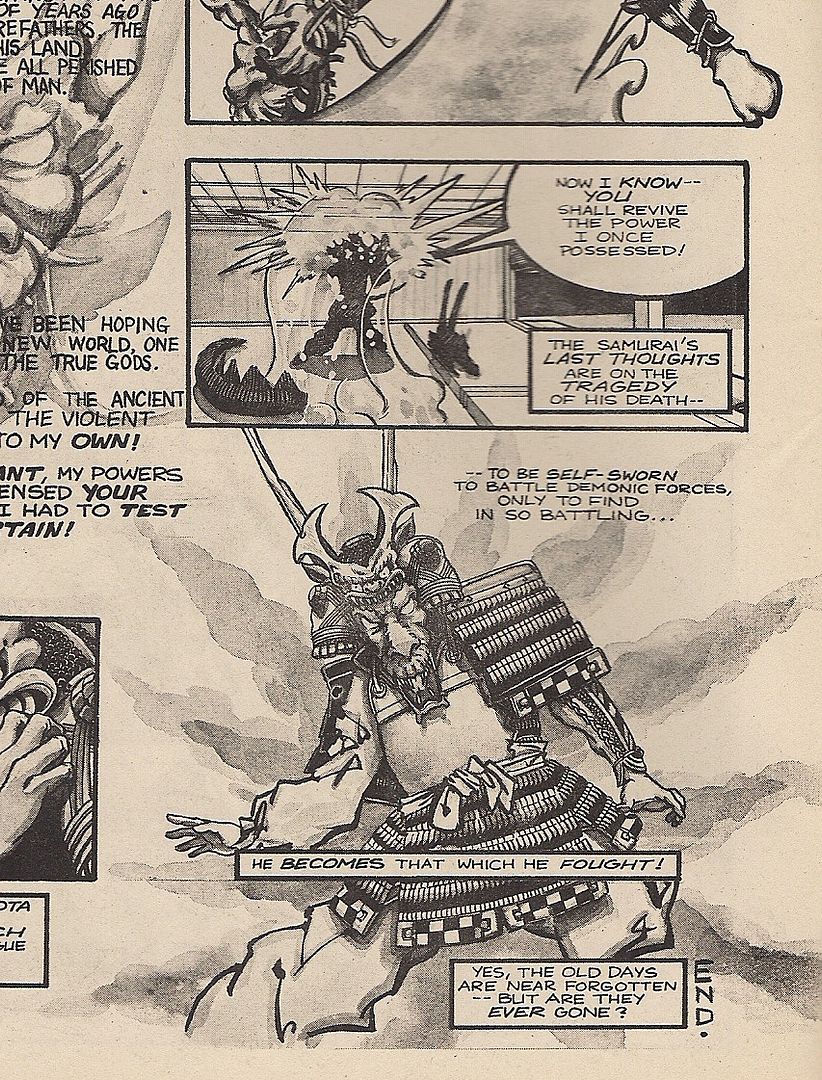

I haven't gotten hold of any of these other comics, just Star*Reach #7. Mukaide's art isn't the kind you stop to notice; you look at his story of a samurai fighting a demon only to pass the test to become a demon himself (ha ha ha ha haaaa!) and you imagine a 1977 comics reader blinking a few times and going "huh, Japan," having maybe seen some televised anime before or communicated with fellow enthusiasts preparing to ramp up first generation fansub operations. You'd have had to physically go to Japan to encounter any other manga at that point.

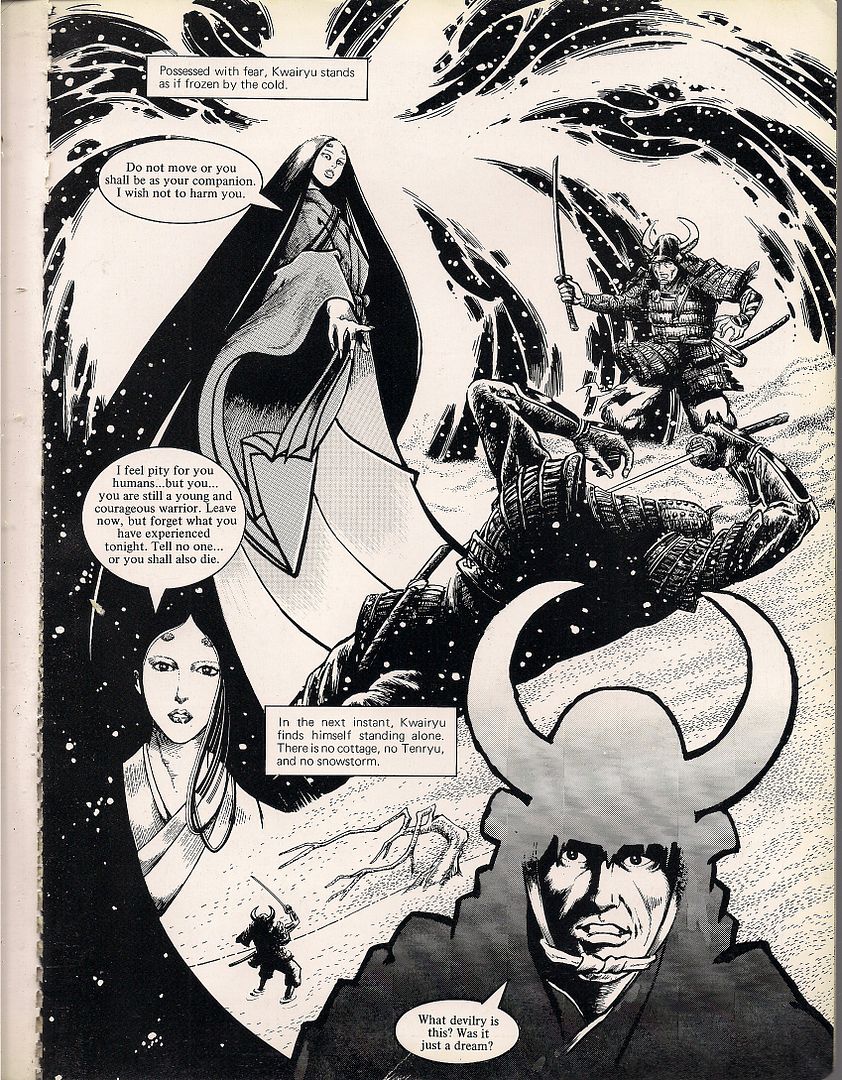

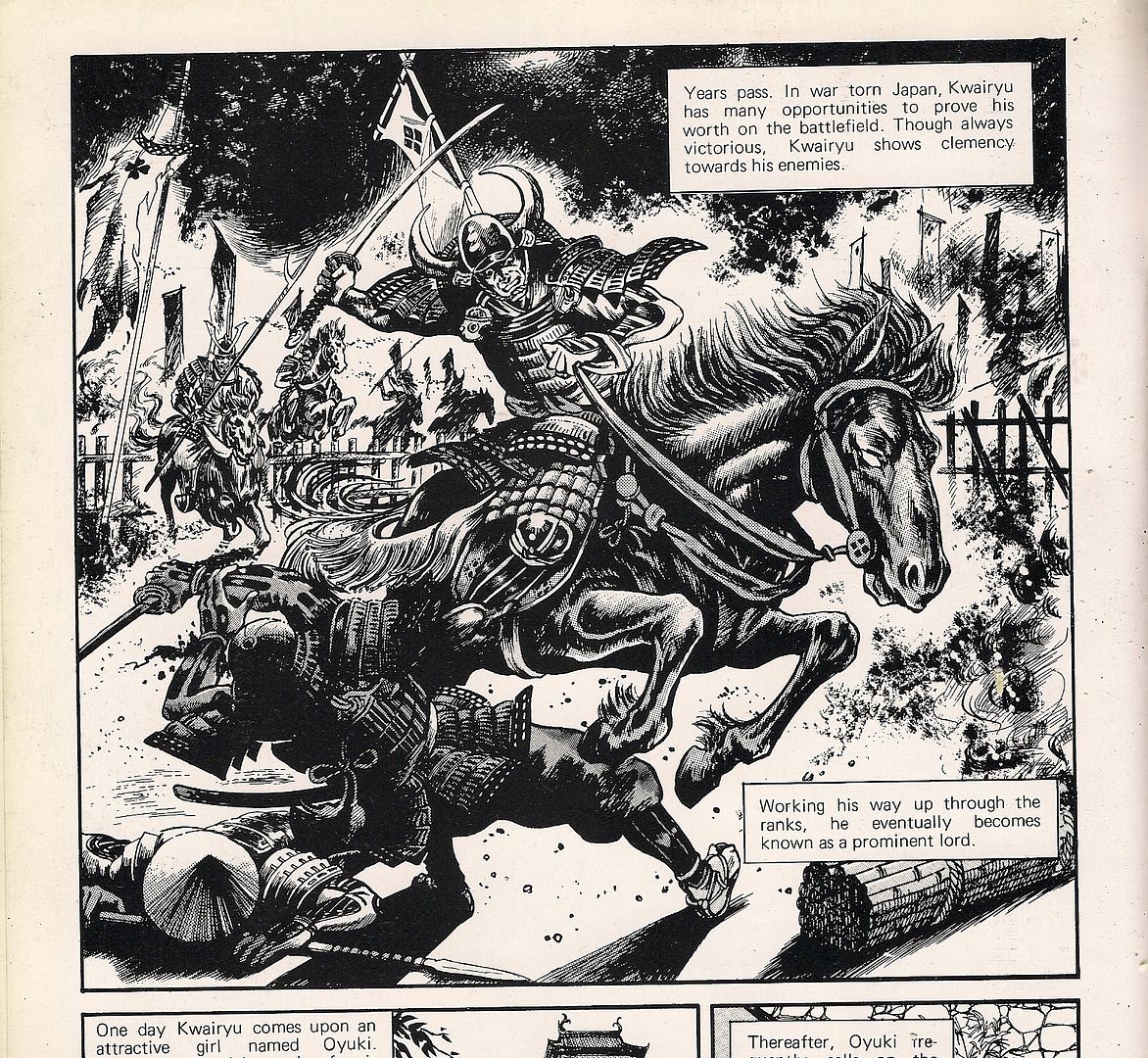

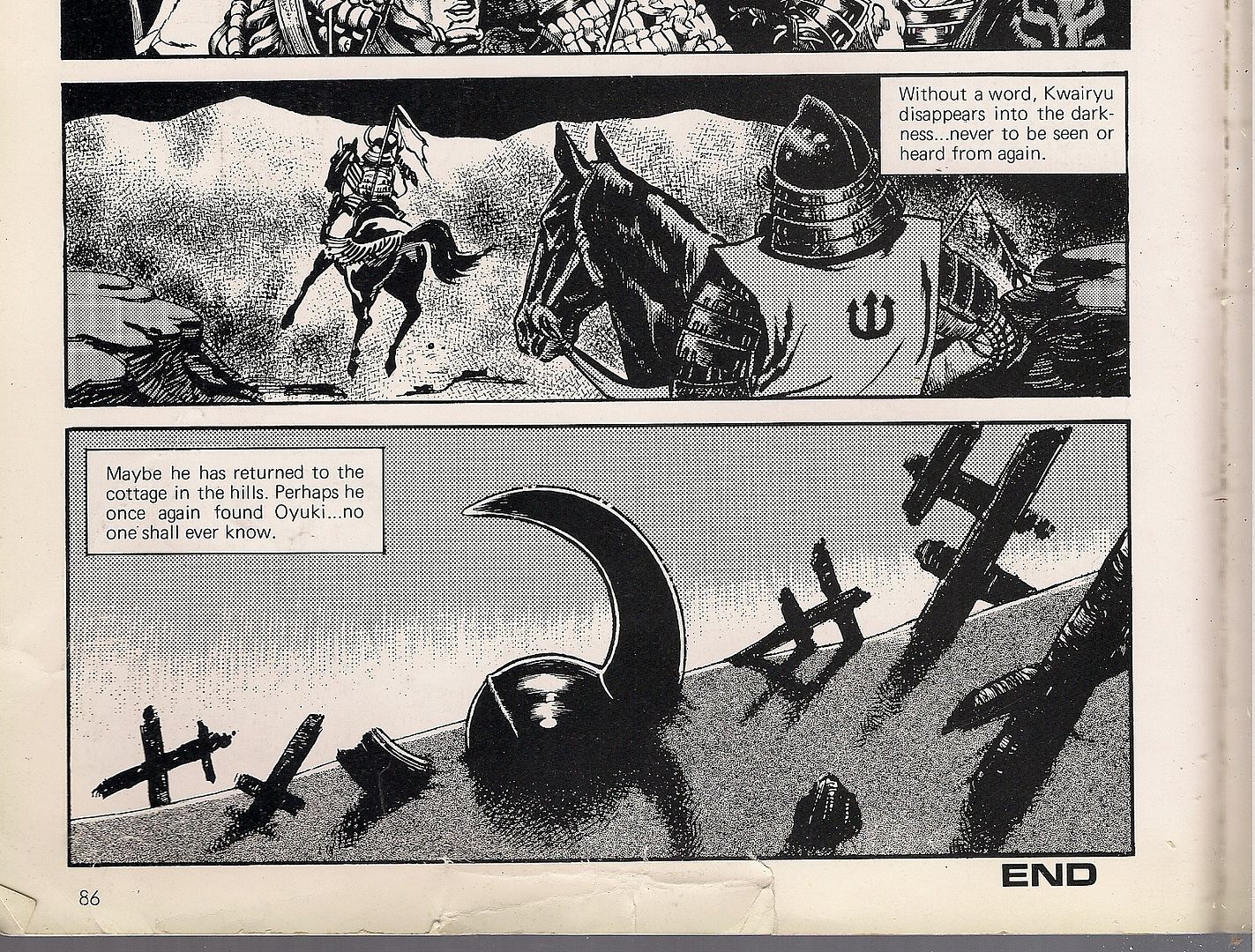

By the time Mukaide edited Manga his draftsmanship had gotten noticeably better, very design-oriented with stylish use of blank or toned space. His story was titled The Promise, concerning another samurai's encounter with a spirit. Poor Kwairyu is a survivor of a lost war, only looking for a place to rest his war-weary bones for the night, but his companion winds up frozen solid when they enter the home of a pure white woman. She takes pity on Our Man, but warns him that he's as good as dead if he ever tells a soul what he's seen.

This is an old tale, an encounter with a Yuki-onna, a spirit first brought to English in Lafcadio Hearn's 1904 folkloric tome Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things, which saw its version of the story adapted to the screen by director Masaki Kobayashi in his 1964 anthology film Kwaidan. I first encountered it as the basis for the Lover's Vow segment in Tales From the Darkside: The Movie, which may not have the same cineaste cachet, but also added gargoyles, so it totally balances out.

It was a poetic choice for Mukaide, suggesting an early meeting of East and West through Hearn's study, charging his editorial duty with metaphor. We can get fancy with this. Kwairyu begins to thrive after his chance meeting with the white woman, as does Mukaide, his writing partner Hirota frozen after their own early encounter with Western comics. Manga was the biggest, most complicated campaign he ran, full of striking forces in effective dress. The end was already drawing near.

Did I forget to define mono no aware earlier? It's a literary concept that came up in study of the Tale of Genji, then grew to become a vital trait of Japanese art in general, like a deep dream image suddenly given words to describe it and thereby made memorable while awake. Put simply, it's the idea that nothing is so lovely as when it is fleeting - an appreciation of the ephemeral qualities of living. A tiny pang, an ache at seasons passing, of romance quieting, of sweet youthful rituals put away, sakura suspended in mid-air, and, most profoundly, the scent of yellowing paper wafting up from an open longbox.

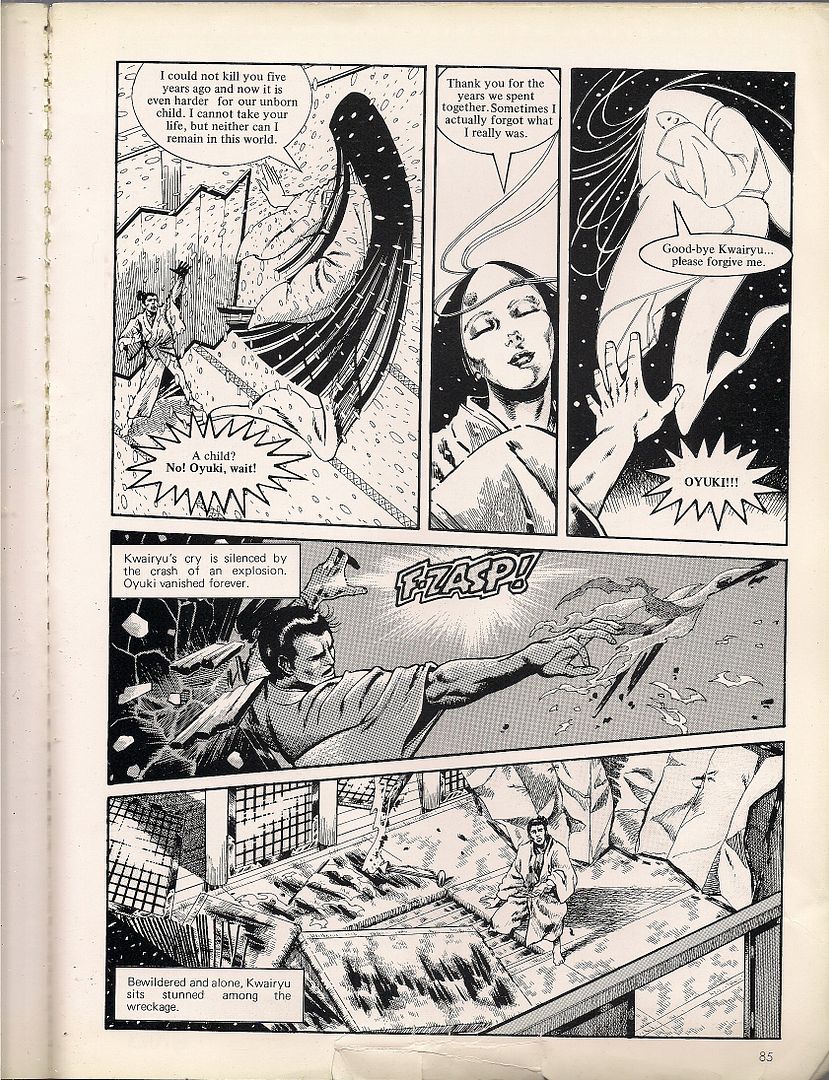

Kwairyu meets a wonderful woman. They marry. She swoons and her breasts are shown for the reader. Mighty Kwairyu comes upon the ruins of that snowy home from years ago. His wife lays nude on a black swipe across the top of a page. Foolish Kwairyu tells her of the spirit, which is of course her. It begins to snow indoors. Time is changing.

I don't know when Manga was published. I don't know where it was sold. I don't know how well it sold. I don't know what happened to Executive Managing Director Tadashi Ookawara. I don't know if I'll ever see half these artists in English again. But they were here. I know what Manga was.

And Masaichi Mukaide, to the best of my knowledge, was never seen in English again.

***

(This post is dedicated to the memory of my beloved personal copy of Manga, which cracked its spine and ceded its glue as I scanned the above images, scattering its pages, boldly giving its life for the proud cause of illustrating internet blog posts here at savagecritic dot com. Our time together was so short, but oh how we burned, you at my bosom, vintage manga comic book. Pie Jesu Domine, dona eis requiem. Amen.)

(198X-2009)