My Life is Choked with Comics #16 - Panorama of Hell

/![]() Drop your glasses, shake your asses. My column on comic books has returned.

Drop your glasses, shake your asses. My column on comic books has returned.

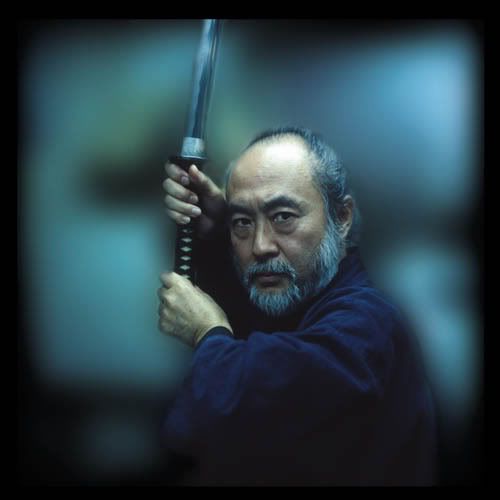

THE KILLER: HIDESHI HINO

Here's our man, manga artist, filmmaker and swordplay aficionado Hideshi Hino. He is a living legend of Japanese horror fiction, manga in particular. Here we see him dressed as every comics artist is at some point, often on the day their spouse decides to leave them, but Hino belongs in such garb.

Trouble, as you might suspect, runs through his blood.

I. Kill Your Family

Hino was born in Manchuria in 1946, in the midst of the post-WWII twilight of Japan's occupation. His grandfather, whom he did not know, was a yakuza, the head of a gambling ring, and not above using his kids as lookouts for the police. But Hino's father had become a railroad worker by the time of the boy's birth, facilitating the flight of Japanese from the region.

The family soon reached Japan on their own, where the father became a metal craftsman, and the son grew. Hino decided at a young age to become a manga artist, in the wake of the 1959 debut of Sanpei Shirato's Ninja Bugeichô (Chronicle of a Ninja's Military Accomplishments), a sprawling action comic boasting relatively realistic art and a sharp, class-conscious political awareness. The boy took early inspiration from the famously surreal children's mangaka Shigeru Sugiura, and later became influenced by alternative manga godfather Yoshiharu Tsuge. The eventual result:

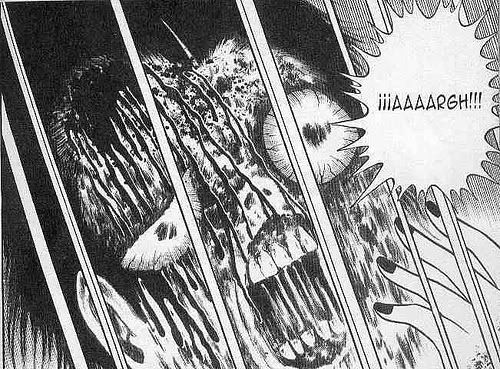

Hino's earliest works appeared in the late '60s, in arty, progressive manga anthologies like Garo (named for a Shirato character) and COM (founded by Osamu Tezuka), but he soon made horror his forte; his first such work was 1969's Zoroku's Strange Disease, a Ray Bradbury-inspired fable about a mentally-challenged recluse whose body erupts into "rainbow-colored neoplasm," much to the revulsion of everyone in the nearby village. Zoroku is cast out, forced to live by eating maggot-strewn animal carcasses; his boils explode in the rainy season, and he vomits rainbows of ooze. But the colors of his secretions are so vivid that he uses them to paint wonderful, horrible pictures, and he eventually transforms into a turtle with a magnificent color shell and bleeding eyes, finally abandoning human society altogether.

It was a popular story, and ran in a children's anthology, where I suppose neoplasm was big. Hino kept at it, his visual style rotting into a warped spin on loose, fat-faced kid appeal comics. Blood and pus would often drip or spray, and bodily mutation became a fixation. The genre would eventually make him famous, and his works would be kept in print and adapted to film, and all that. He made a lot of stuff.

To be blunt, some of Hino's miscellaneous horror stories, from what I've read, are uninspired space filler; that's how it goes for all the Japanese genre specialists who've had the honor of getting lots of work released in English. And I haven't even gotten to a lot of Hino's more current material, post-'90s stuff, but I've read that it gets very poor indeed - lots of straining to match his round, dripping, kiddie-comics-gone-bad style to 'mainstream' demands (or at least hiring assistants to do so), lots of distracting computer effects and recycled, uninspired plots. Even some of his prime period stuff is loud, stretched-out and formulaic.

Yet the best of Hino begs some telling comparisons with his peers. For example, unlike the early works of fellow future horror manga legend Kazuo Umezu (of The Drifting Classroom), which are sprinkled with affirmations of traditional gender and social roles via normal people's struggles against the weird, many of Hino's comics presented the unusual or fantastic as something people needed to cope with in order to drag some happiness, however fleeting, out of life. A woman might give birth to a lizard, one that grows to eat birds and dogs, and, ok sure, maybe the face of the neighbors' kid, but it's always clear that it's better for the citizens of Hino's world to get the fuck over themselves and adapt to the ugly and strange nature of the world.

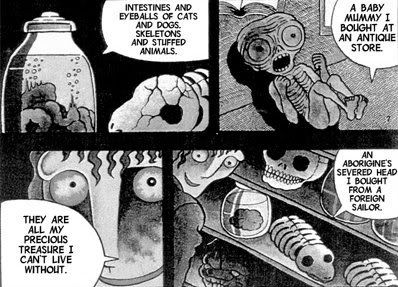

Elements of autobiography sometimes seep in. Common to some of Hino's stories is an artist character -- a painter, mangaka, whatever -- who delights in sick and terrible things. Sometimes he is explicitly identified as Hino himself, and sometimes he is explicitly identified as someone other than Hino, but he's always understood to be at least an awful alter ego.

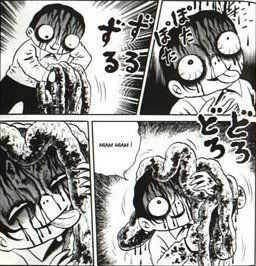

In the early '70s story A Lullaby from Hell, perhaps the character's first appearance, Hino (as he's identified) boasts of his many ugly pets and terrible items. He confesses to having been "a sickly, depressing kid," and tells us about his brutal father, demented mother and gangster brother, and his early love for torturing animals and playing make-believe games in which he'd command devils from Hell to devour and disembowel crucified souls. The magic of Hino's work is in seeing his lil' googly-eyed kid self tittering "tee hee hee... heh heh heh..." in front of a gigantic heap of bloody corpses, all drawn in a friendly, almost doodled style.

(right-to-left, people!)

(right-to-left, people!)

Young Hino then discovers he has the power to imagine the means of death for anyone he doesn't like, and have his wishes come true (typical child fantasy; shades of Death Note too). Life becomes grand, because Hideshi Hino fucking hates humanity; Mom plunges into a sewer, Dad gets ground into mush at the factory (economic miracle!), Bro is stabbed in a fight, a rival comics artist is struck by lightning, a mean editor is banked off a speeding car into the path of an oncoming steamroller... what delight! The story ends with Our Author crowing about how he now has plenty of time to draw comics, and declaring that you, the reader, will die in three days since you've learned the secret to success in comics.

"Die. Die! Fall. Fall!! "Fall down to the bottom of the Hell! Fall!"

This mix of self-parody, self-pity, fantastical quasi-autobiography and pure, full-bore hate would inform other works of Hino's.

In 1982, he would remake and expand A Lullaby from Hell into a full-length book, perhaps his masterpiece, Panorama of Hell.

II. Kill Your Work

But hey, you don't need to take my word for all this; believe it or not, Hino is one of the most-published of 'classic' manga artists in English-speaking environs. First and foremost, DH Publishing has a 14-volume series of books dedicated to the artist, Hino Horror, from 2004.

In 2006, Dark Horse released its own collection of Hino shorts, Lullabies from Hell, containing all the stories I've mentioned above.

Just last year, Last Gasp brought over a nice hardcover collection of color stories and images, The Art of Hideshi Hino.

And that's just the newer stuff. The comics stuff.

Really -- and I hope you don't mind a little detour here -- if anything propelled Hino into the cult figure stratosphere, it was a movie that initially didn't even bear his name.

Have you heard of Guinea Pig?

Don't click this. It's gross!

III. Kill Your Audience

I like to imagine it was a sunny, breezy day in 1985, birds chirping and children laughing, when Hino was approached by producer Satoru Ogura with the idea of making snuff movies. Fake snuff movies, of course, but vhs quickies that would employ the most advanced makeup effects (and the least advanced filmmaking technique) to blur the line as much as possible. There would be no credits, at least not on the first release, and the ad campaign would pretend that the material actually was found footage of some young lady getting murdered, on video, over the course of an hour or so.

Ogura was an admirer of Hino's manga, and figured he'd be up for a little creative filmmaking; he was right. But little did Hino know he was to be involved in a grand adventure, involving fame, money and Two and a Half Men cutup Charlie Sheen.

There isn't much to say about the initial pair of Guinea Pig movies; Ogura himself created the first, Devil's Experiment, and Hino the second, Flower of Flesh and Blood. They are literally nothing more than footage of a pretty girl being tortured, disfigured, dismembered, etc., until she is dead. The tapes did very well upon their 1985 release; Hino's entry, depicting one of his typical collector characters ritualistic chopping and carving of a body into the blossom of its subtitle, was supposedly was among the top 10 best-selling cassettes in the nation for two months.

As Hino told interviewer Tomo Machiyama in The Comics Journal Special Edition Vol. 5 2005:

"I really wanted to shock everybody with Guinea Pig. I wanted people to remember who I was and what my talents were, and take them by storm."

The series moved to a larger publisher after the first two episodes, and began to adopt a more typical 'horror movie' approach. Hino returned for the 1988 fourth installment, Mermaid in a Manhole, which is filled to the brim with his pet themes. The plot concerns an even more typical Hino stand-in artist character, who one day discovers a living, wounded, diseased mermaid down deep in the sewers.

In what functions as an extended callback to Hino's very first horror comic, the Zoroku fable described above, the artist takes the mermaid back to his studio and, at her request, uses the liquid hues of her rapidly decomposing body to paint her portrait; the self-absorption of Hino's original comic is thus transformed into a (somewhat) more mature reflection on artists striving to capture a fleeting beauty in their work, even as the world falls toward ugliness as they labor.

Lots of sticky effects too.

Things went well, all things considered. The series weathered the infamous 1989 media frenzy following the Tsutomo Miyazaki case, the so-called Otaku Murders, when one of the later volumes of the series was found along with all the anime and porno in Miyazaki's apartment. A 'best-of' compilation was created in 1991, various copies found their way into the Western world... it was all going well until Charlie Sheen got involved.

There's multiple versions of this story, as you might suspect. I'm going off the official R1 dvd history page (every movie in the world is out on R1 dvd, by the way, possibly including that home video of my dad pretending to be Max Headroom that he made when I was five). It so happened that one day Mr. Sheen came across a splatter movie compilation tape assembled by Chas. Balun of the horror magazine Deep Red; the action kicked off with Hino's Flower of Flesh and Blood. No doubt left agog at Hino's consummate artistry, the Hot Shots star mistook the footage for a genuine no kidding for-reals snuff film produced in the savage land of Japan, where life is cheap, and promptly contacted the MPAA (I bet they even refused it an 'R'!), which then summoned the FBI.

Luckily, the feds soon puzzled out that the movie was only fiction, possibly due to the existence of a 1986 'making of' documentary; snuff movies theoretically shouldn't have a lot of behind-the-scenes scoop available. Or maybe they noticed that Flower of Flesh and Blood climaxes with the girl's head sproooiiinging off her shoulders and bouncing against a wall.

In the above-mentioned Journal interview, Hino notes that he was never contacted by the FBI, although he would have gone to the US to chat if asked. Maybe he could have met Charlie Sheen.

But what to make of Hino? All this shock, mayhem (in the legal sense), slime and pitiable longing.

There was, at one time, a desperate culmination.

IV. Kill Yourself

So, who remembers the manga affairs of Blast Books? Covers designed left-to-right, contents produced right-to-left? They had three Hino-related releases, which I'll present in reverse order.

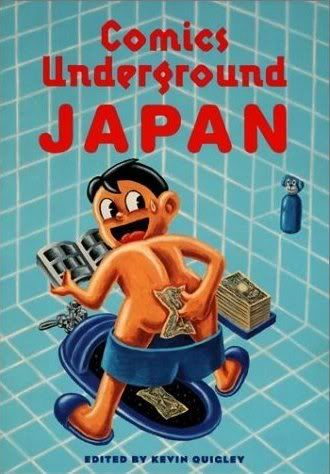

In 1996, a Hino story (Laughing Ball, 1991) was featured in the excellent, Kevin Quigley-edited anthology Comics Underground Japan, which I'd urge you to find a copy of. It's a great sampler of the 'alternative' manga scene circa 1985-92, and Suehiro Maruo's Planet of the Jap is probably one of my favorite short manga stories ever.

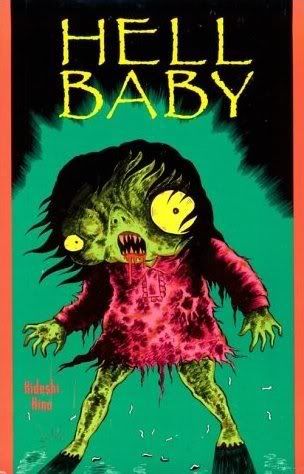

In 1995, Blast released a standalone Hino book from 1982, Hell Baby, the tale of a deformed child's adventures. I haven't read it, but I suspect most of Hino's common themes are in play.

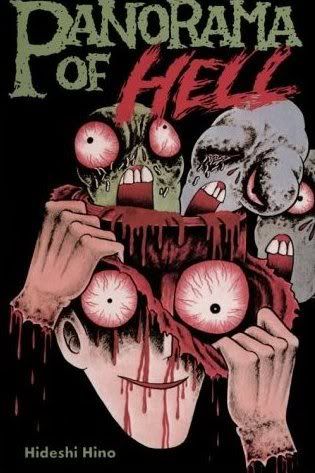

But the first of Blast's Hino releases was the crucial one. It came out in 1989, 198 pages, with an English adaptation co-written by Screaming Mad George(!!). It's way out of print; I found a cover price $9.95 copy sitting forlornly in a comic shop. Rescue this if you see it:

Panorama of Hell is one of the oddest manga I've ever read. It's the sort of thing I can't imagine being released to the general public outside of a culture where comics stand with prose novels as popular literature, therefore allowing even small publishers wide access to the public.

Hino was in a bad way in 1982. Anthology work had dried up for an artist like him. He was out of money, and releasing books mainly through cut-rate publishers. He suspected the horror genre was not long for the comics world. He decided that Panorama of Hell would be his final statement, his farewell. He supposedly drew it quickly, in a booze-soaked, sleep-deprived binge. As I've mentioned, it's a remake of an earlier short story; it's also inspired by a 1918 short story from literary giant Ryunosuke Akutagawa. But it reads like a summary of everything.

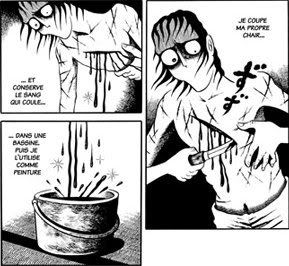

As expected, the Artist narrates. He's not Hino this time; he actually mentions that his daughter is a fan of Hino's comics. And for the first 1/4 of the story, he does absolutely nothing but detail the mechanics of his strange world, and the interests of his family. He lives in an awful, violent Japan, painting pictures of it with his own blood and puke; a guillotine atop his home cuts the heads off people, the heads sent down a railroad, blood flowers blooming from the spilled gore. The bodies are burned in huge ovens, leaping and dancing as they crisp, until they go to the graveyard, rising up at night to wear ruined animal heads hung on crosses. And etc. And etc.

Hino's art is at its best here, oscillating between accomplished cartoon renderings, illustrational flourishes and furious scratched and dotted depictions of violence and gore. There is hardly a page in this book without violence or bloodshed; it is relentless, and its endless (yet logical!) opening chain of gruesome social mechanics make it seem like the rantings of an obsessive-compulsive after too much splatterpunk, although its ritual nature joins it to Flower of Flesh and Blood in the Hino catalog. It doesn't help when the Artist reveals how he loves to lick his happy children when they come in from collecting eyeballs for his collection, or how his wife runs a tavern for the headless walking dead, feeding them by carving mouths into their stumpy necks.

However, intent slowly reveals itself. There's hints early on -- one of the Artist's kids drawing a picture of men fighting over food, the state execution flavor of the beheadings -- but things really kick into gear when the Artist offers an account of his family history, one that plunges the story into surreal fantasy autobiography.

The Artist's grandfather was a yakuza and a gambler, prone to big winnings, bigger losses, and violent sex with grandma. When rivals cut him open on the road, piles of dice spill from his guts. The Artist's father moved to Manchuria, after a harsh childhood; in 1945, a ray from the bombing of Hiroshima struck his wife, portending the Artist's birth ("I was born the son of a defeated invader of that country of hell..."). The couple and their young child fled Manchuria after the War, witnessing death and suffering on the road, blood flowers blooming, driving the woman mad.

You see? Slowly, surely, the story coheres into parallel account of Hino's family history, kissed by evil magic; all the pain is encoded. I don't know if Hino's brother was a driven street fighter, like the Artist's is here, though I know from the Journal interview that he wasn't beaten into a coma and buried in the snow; no, he fell from a motorcycle and went into a coma. And he was in bad shape when he woke up, and the Artist's brother literally transforms into a moaning blob of flesh. After that little reminisce, the plot grinds to a halt for two solid pages of the Artist facing the reader, ripping his hair out, and screaming, screaming about how he all he knew how to do was draw, and how he couldn't help his brother out.

The comic adopts a gale force of psychological accumulation; you can't tear your eyes away from the confessions. There's a risk in trying to learn from these tales the Artist tells, because we don't know too much of Hino. Was his mother really mentally ill? Did his father truly hit him a lot? Even the broadest strokes seem primed to scratch against the reader, like when the Artist as a child is hung upside-down and caned by his mother, her breasts spilling from her robe, and he admits to learning ecstasy from pain. For further Mommy Issues, see Hino Horror Vol. 1: The Red Snake.

Eventually, the plot to A Lullaby from Hell kicks in, this time with the young Artist molding a clay model of the Hiroshima mushroom cloud, naming it the Emperor of Hell, dousing it in animal blood and wishing for his enemies to die; it works, and provides the finest inspiration for his hellish paintings. The boy grows, and the Artist becomes more ambitious: ocean disasters, train wrecks, plane crashes, the Falklands War - our man is behind them all. And it turns out we're just in time to witness is greatest, present work, the creation of the Panorama of Hell through the simultaneous detonation of all the world's nuclear weapons! Fuck!

What follows can best be described as a full-scale nervous breakdown on the comics page. The Artists needs as much human blood as possible to make his dreams come true, so he graps an axe and hacks up his family - but his wife is only a mannequin, his children dolls, his brother a sleeping hog. Sample lines from one page:

"Fucking hell!"

"Hell!"

"Hell!"

"Gasp... gasp..."

"Brother!"

He runs outside and hacks down a wall he's never seen the other side of. He's then confronted with a gaping female mouth on the horizon -- like a pair of Rolling Stones hot lips -- with a glowing bridge issuing from his maw over a black sea of blood and wailing bodies. A giant revolving lantern rises from the sea, containing his whole family history, then exploding into a drenching blast of gore. The Artist vomits, declares nuclear destruction to be his true father, and vows to be the last person left on Earth to paint the awesome beauty of annihilation. And he turns toward the reader, finger pointing:

"You will die!"

"You and you and you will die!"

"He will die, and she will die, and you will die!"

"You will all die!"

And he wheels back on the glowing bridge, fading into the ash snowfall of the crematorium, and flings his axe toward the reader, drawing closer... closer... closer...

Until it's The End.

I hope my description has given you a sense of what this book is like, although there's no substitute for reading it, if you can track it down. It is a work of supreme misanthropy, and astonishing intimacy. It is political, matching up colorized details of the author's troubled life with the violence that's marked his nation since the end of its empire-building ambition. The Artist is a child of defeat, and no economic revival can hide the tradition of cruelty that continues in homes and minds.

If not a panorama, it is a map of Hell: the mental state of a proud, lost native of a lost country, guilty that all he can do is collect the elements of a collective past -- all abuses -- and make some art to show the world how a man feels about it. Pity not Hino, here - lament his circumstances, and try to dodge the twirling blade.

Hino wouldn't work in comics again until 1985, the year of Guinea Pig.

"There was still something left inside me," he told Machiyama, in the Journal.

And the atrocity exhibition, mental blood flooding it, opened once again.