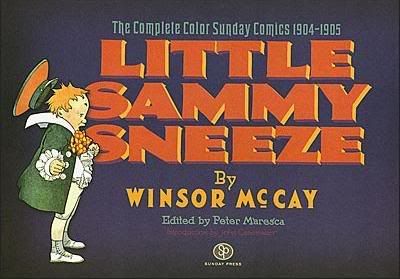

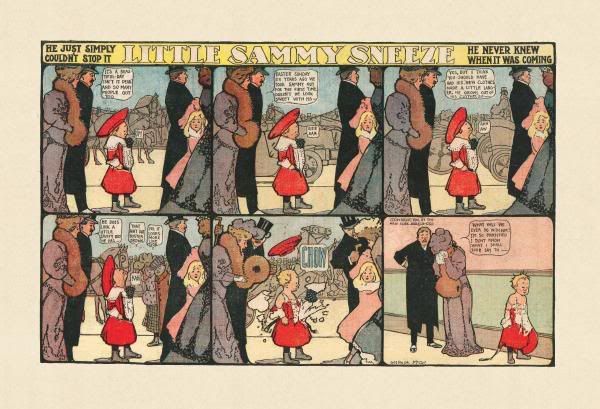

My Life is Choked with Comics #15 - Little Sammy Sneeze: The Complete Color Sunday Comics 1904-1905

/

The true meaning of Christmas, as dozens of imaginary theological scholars have told me, is swapping boasts about awesome gifts. It's all in the Bible, I think somewhere around the Book of Numbers; maybe that isn't where you'd expect to find information pertaining to Christmas, but life does like to carry its surprises.

I got this book as a gift. It's a dandy.

Riding high at the extravagant front of today's Golden Age of Reprints is Sunday Press Books, which attracted a lot of attention last year for its first publication, Little Nemo in Slumberland: So Many Splendid Sundays!, a very large (21" x 16.2"), very expensive ($120.00), 120-page 'best of' presentation of episodes from the famous 1905 newspaper creation of one Zenas Winsor McCay, who absentmindedly misplaced his first name somewhere on the road to fortune. Pursuing the "imperfect ideal" of vintage newspaper reproduction, Sunday Press struck a nearly perfect balance between refurbishing McCay's famous artwork, and preserving the off-white backing & slightly imprecise color printing of period technology. The result, presented in hardcover on fine paper, wowed many and sold more.

The publisher has since solidified its position in the comics world. Earlier this year it teamed up with designer Chris Ware for Sundays with Walt & Skeezix, a similarly deluxe sampling of Frank King's Gasoline Alley Sunday pages, obviously poised as a premium companion tome to publisher Drawn & Quarterly's ongoing, Ware-designed Walt & Skeezix dailies series. And now comes Little Sammy Sneeze: The Complete Color Sunday Comics 1904-1905, a comparatively budget-minded ($55.00), landscape-format (11" x 16"), 96-page hardcover, devoted primarily to the aforementioned McCay's second most famous newspaper strip to star a little kid.

Naturally, my first thought upon finishing the book was to present my thoughts as part of the unchallenged wave of prolificacy that is this column. Let's get right to it.

A COLLECTION OF FIVE THOUGHTS REGARDING THE FINE BOOK IN THE TITLE OF MY COLUMN TODAY:

1. Books, Unsurprisingly, Tell Stories

One interesting side effect to the sheer variety of vintage reprint compilations on today's shelves is that it's become easier to discern the distinct character of each. Today's compilations often come equipped with all sorts of historical supplements and bonuses, and often a particular design aesthetic - this is especially evident in collections of aged newspaper comics, where packaging and context can go a long way toward defining a 'tone' for the old material to ring with, if only through association.

Those Ware-designed Frank King books exude wistfulness and delicacy, bolstered by those dozens of silvery b&w photographs of family and landscape, while its essays emphasize King's sensitivity and devotion in matters both artistic and personal.

Fantagraphics' Peanuts books rely on muted cover colors, sporting reflective introductions by well-known personalities, the totality of which casts Charles Schulz's work in a nostalgic, gently melancholic light.

In contrast, Fantagraphics' Popeye hardcovers are tall, loud things with blazing dot colors and die-cut covers, as if each individual copy had been broken over the head of a small animal in preparation for the two-fisted comics fun rustling within. Eat your goddamned spinach.

But these are comprehensive projects, aiming to compile, in as perfect an order as possible, a large, particular span of a work. Sunday Press does not release that type of collection; their books excerpt from larger runs, and thus the very arrangement of the comics inside becomes a variable element of each book's character.

So what is the character of this Sammy Sneeze book? Simulation!

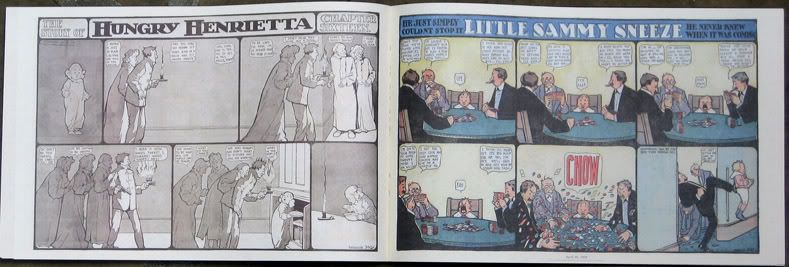

You see, this book doesn't just present a bunch of Little Sammy Sneeze strips. It also features the complete run of another, even more obscure McCay strip of 1905, The Story of Hungry Henrietta, along with selections from three additional, non-McCay strips: John Prentiss Benson's 1904-05 The Woozlebeasts, Gustave Verbeek's 1903-05 The Upside-Downs of Little Lady Lovekins and Old Man Muffaroo, and Verbeek's 1905-11 The Terrors of the Tiny Tads. Note the matching years - that's the key.

Not content to simply make its sturdy archival pages look like old newspaper clippings and match the appropriate period size (11" x 16" being about how one of these features would be read on half a broadsheet of 1905 funnies), Sunday Press is now trying to replicate some part of the action of reading old funnies from the New York Herald. One side of each of this book's pages contains a full-color Sammy strip, while the other side features a monochrome strip from among the four others, all of which might have actually been found on the other side of Sammy in 1904 or 1905, with all lack of color typical for a time period in which only half of the paper's Sunday strips got full benefits.

It's a novel approach, and also a handy way to fill out the book, given the restrictions of its feature presentation. Little Sammy Sneeze initially ran weekly from July 24, 1904 to December 9, 1906, with intermittent daily appearances occurring in the next decade, but the careful reader will have already noticed that this book only collects the complete color Sundays, which ran for the years of the title. Other Sammy installments, including the famous panel-breaking number seen in altered form up top (and dutifully pasted in Sunday form into the book's Introduction), are not included. Among the supplementary materials by the likes of editor Peter Maresca, McCay biographer John Canemaker, historian & McCay biographical fiction writer Thierry Smolderen, comics scholar Jeet Heer, ComicsResearch.org director Gene Kannenberg, Jr. and miscellaneous compilation regular Dan Nadel, it would have been nice if a concise history of the strip's publication vis-à-vis the book's contents had emerged.

But I'm willing to let some things slide in light of intuitive construction. The word Complete isn't the focus of the book; it's the effort made to bring the reader into the seat of the work's original primary audience, and there are some revelations that eventually rise through that.

2. Adults Are Merely Human; Children Are Monsters From Hell

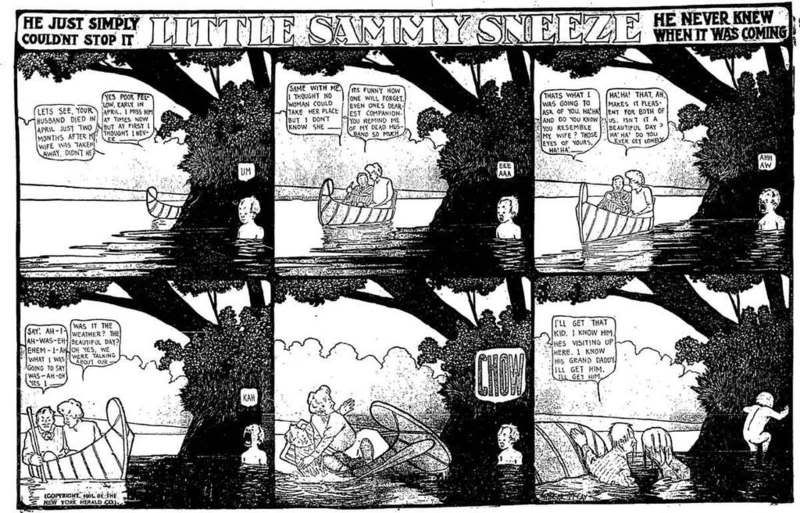

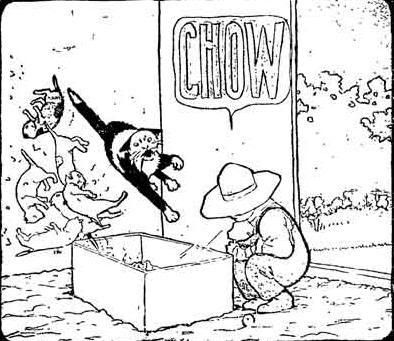

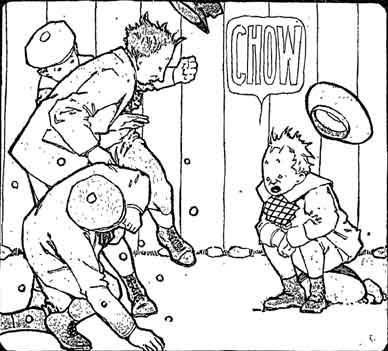

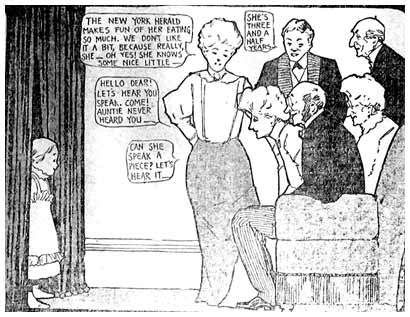

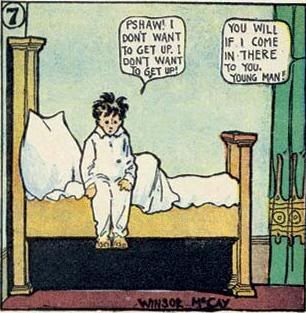

Here is how your typical Little Sammy Sneeze Sunday page goes.

These old b&w images are typical for some McCay collections, as well as great websites like Barnacle Press, but be aware that the book is in lovely full color.

Sammy's strip is a one-joke affair.

In most episodes, the first four panels depict people or creatures or devices milling around a scene, often fixed in perspective, while the titular foppish lad's sinuses grows more and more irritated. His mouth stretches enormously.

Every fifth panel is the same.

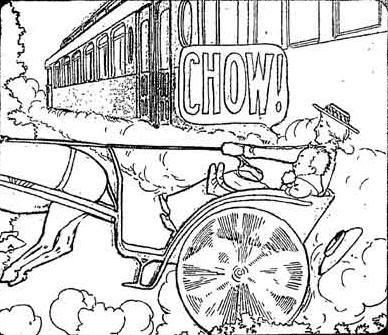

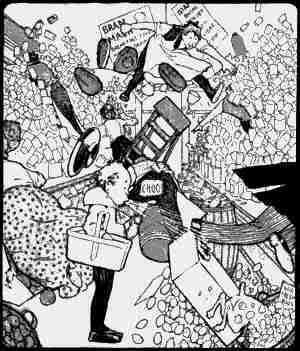

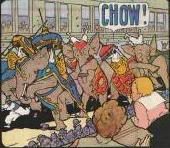

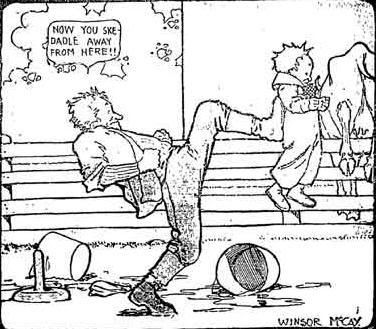

And each sixth and final panel contains some (usually rueful) denouement in which the pieces are put back together, often with Sammy getting a sharp kick in the ass for his troubles. Sometimes Sammy's sneezes are helpful -- foiling burglars or the machnications of that notorious, perhaps not entirely monolithic early 20th century villainy organization the Black Hand -- but usually his nose is nothing but ruin. They vary wildly in power, sometimes acting only to upset a little girl's tea party, but sometimes rocking a train with enough force that passengers demand to know if a bomb's gone off somewhere. Folks are perpetually stymied.

Therefore, as Kannenberg perceptively indicates in his supplemental piece, Sammy is one of an extremely popular character type among newspaper strip children of the time: the Horrible Demon (my title). It's a long and proud tradition, going all the way back to R.F. Outcault's Mickey Dugan -- the famous Yellow Kid -- and extending into the likes of Rudolph Dirks' Hans und Fritz antics, which started up in 1897, and still runs somewhere today as The Katzenjammer Kids. But the king shit miniature Satan of the time was another Outcault creation, the eponymous tot of 1902's Buster Brown.

There's a lot of particularly common ground between Buster and Sammy. Both characters are American-born children of well-to-do parents, indicating a break from the earliest child characters of US funnies, which tended to be poor, and not entirely assimilated away from their obvious immigrant heritage.

Their antics were supposed to be earthy, I guess, although they can carry some charge of laughter toward the impolite ways of the Other. Outcault, at least, couched his characterizations in terms of the rambunctious soul of Our United States, the Melting Pot, while some artists, like Dirks, actually were immigrants of the ethnic groups they focused on. But characters like Buster Brown brought that same spirit into the finer homes of America, mercifully lacking the labored dialect humor of preceding ragamuffins, and contextualizing their wicked behavior as not just a specific quality of an American class, but of childhood.

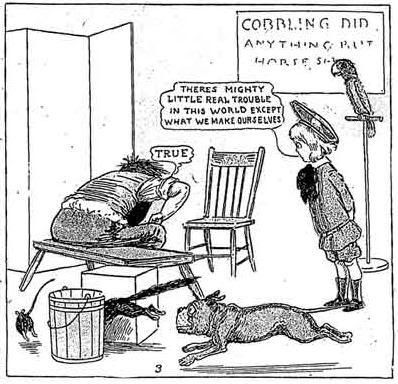

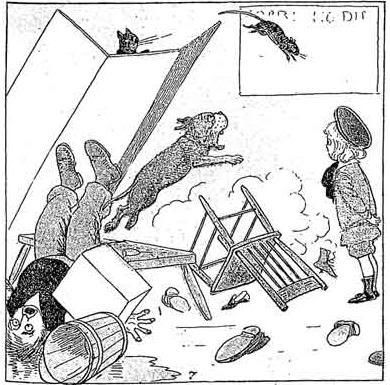

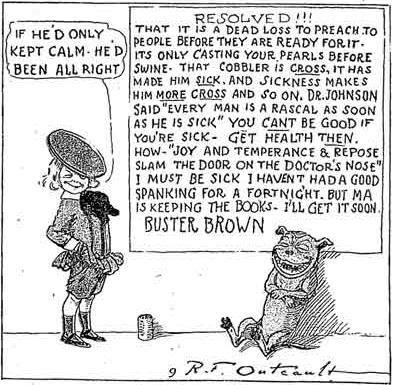

I like Buster Brown a lot. It's direct and funny, often beautifully drawn, and sometimes wonderfully ironic, a quality rarely associated with comics over a century old. It's not just that Buster misbehaves in a violent (if nominally good-natured) way, it's that each strip features a special moral, delivered in a large caption, in which the tyke resolves to take the week's lesson to heart, if often in a way contrary to typical moralizing.

But Sammy Sneeze is not Buster Brown.

McCay's literary and aesthetic values are plainly different from Outcault's. Sammy not only doesn't have control over his sneezes, he doesn't really have any personality at all. Actually, he doesn't even talk - all of the words out of his mouth are simple preludes to the gale-force means of expression indicated by his familial name (and yeah, his dad is Mr. Sneeze, his mom Mrs. Sneeze, etc.). This doesn't prove to be as much of a problem as you might think - not only does the nature of the strip's one and only joke require no verbiage on Sammy's part, but the character's lack of meaningful interaction with the world around him aids McCay's perspective on the character.

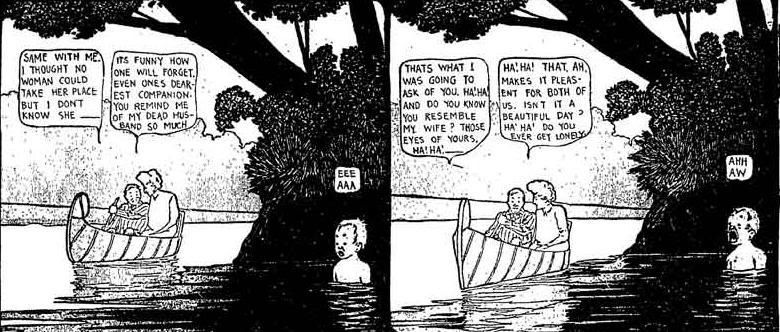

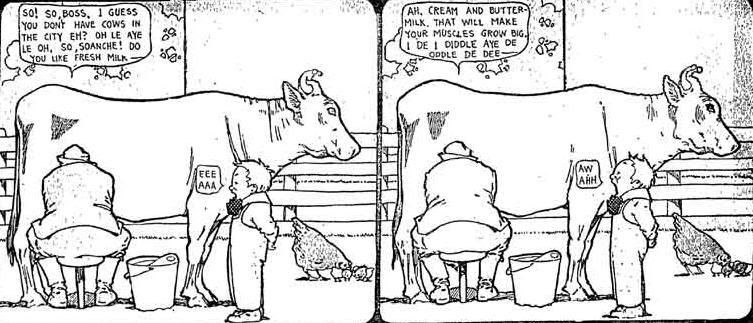

Canemaker makes note of McCay's use of fixed backgrounds as presaging his pioneering work in animated film (starting in 1911); I'd agree to an extent, but I think the technique works best in the context of the strip itself as drawing out the tittering nature of adulthood, or older children acting in measurably 'adult' ways. It's fitting that Sammy doesn't talk; he doesn't even seem to comprehend, which strikes me as far more reasonable a depiction than the mannered devilry of other naughty kid characters. His naughtiness isn't purposeful, or even 'realistic.' Instead, McCay draws our attention to the chit-chat of maturity by the activities of the non-Sammy characters, wandering around unchanging scenes. Taking a detail from the full strip seen above:

Some commentators have called McCay a weak writer, in contrast to his superb draftsmanship. I disagree - McCay's writing is stylized and idiosyncratic, and all those Oh!s and Ah!s do tend to grate after a while, but I think his work on this strip is appealing in its dilly-dallying rhythms, with word balloons often ending in incomplete sentences, and thoughts dropped across the span of dialog. It doesn't sound real, but it feels authentic.

More importantly, McCay establishes an environment that seems natural for every character except Sammy, who constantly plays the role of dull onlooker, until his inevitable sneeze upsets everything. It's tempting to read a political motive into this approach: Sammy as the lil' anarchist, deflating pomposity, smashing conformity, and frustrating bourgeois pleasure through absurd destruction. Maybe he went Dada once he grew up and the Great War hit?

But I don't think McCay's work quite plays that interpretation out. Rather, Sammy's surreal, constant reaction to McCay's 'realistic,' constant displays of activity seems more a sign of childhood lashing out comedically at adulthood.

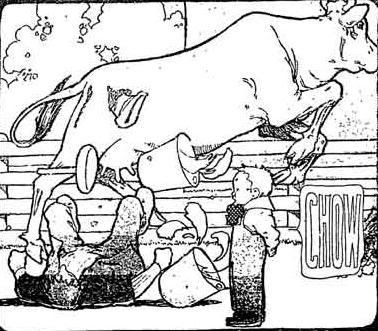

Unlike Buster Brown and others, Sammy doesn't want to cause funny trouble, he absolutely needs to, and his compulsion is always presented in terms of knocking down maturities, no matter how small. It could be a train coming to run him over, or a villain arriving to do him harm, or a show he's watching, or a parade, or other children having a formal party, or a classmate reciting a lesson, or lovers floating down a river, or someone showing him how to milk a cow - any way you slice it, for good or (more often) ill, Sammy sneezes to upset a world he cannot obviously understand.

Because how could he understand it? He's a little child.

And he's only a hellion in that he comes from a place the grown-ups (or wannabes) fail to grasp.

I'll be upfront: Little Sammy Sneeze isn't as funny a comic strip as Buster Brown. Most of the humor hits as soon as you see what kind of situation Sammy has wandered into this week - after that, it's all inevitable. McCay's lovely visuals are present too, of course; nobody of his period could quite draw large places in and out of motion like he could. But the repetition of the strip is beguiling, and it's a fascinating counterpoint to seemingly like-minded comics of its time.

3. Big Helps Out

Speaking of other strips of the time, the book presents alternative views on childlike action through its backup strips. My main reaction: thank heaven for large printing.

The Woozlebeasts, I'm sorry to say, is stone-dead boring. I suspect it'd be the same way at any size, but at least those authentic period proportions help Benson's draftsmanship shine a little better (and note again that the strips included in the book look nicer than what you see here). But it's a simultaneously dour and uninteresting thing, being a series of limericks about unfortunate or allegedly whimsical creatures, which are dutifully illustrated for your pleasure.

This doggerel wasn't particularly new to comics or children's literature, even in 1904 -- just one year prior, McCay himself had illustrated the deeply brow-furrowing Tales of the Jungle Imps to George Randolph Chester's poems -- but we're told (by Nadel, I think - the book's essay layout is kind of confusing) that Benson apparently managed to inspire a number of subsequent features conjoining verse and odd beasts, though I don't think any of them lasted all that long. The Woozlebeasts itself manages to end its run right in the middle of the book's selected time period, so we at least get to enjoy an olde tyme farewell strip.

We're also told that strips of this sort were commissioned as a salve to growing complaints of the ruckus predominant in the naughty kid strips mentioned above. Knowing this makes McCay's enlightened, admittedly gentler take on the tropes seem all the more skillful.

Verbeek's work comes off a good deal better; even his similarly-situated The Terrors of the Tiny Tads, only one episode of which is provided, seems more visceral and spooky and fun. And I'll say with total honesty that this large printing size has facilitated the first-ever time The Upside-Downs of Little Lady Lovekins and Old Man Muffaroo has ever worked for me. You see, it's sort of a trick strip - you first read its six panels as you normally would a comic, and then you turn the newspaper upside-down to read the strip again. All of Verbeek's art is designed to provide different, comprehensible visuals in both directions, for a total of 12 panels.

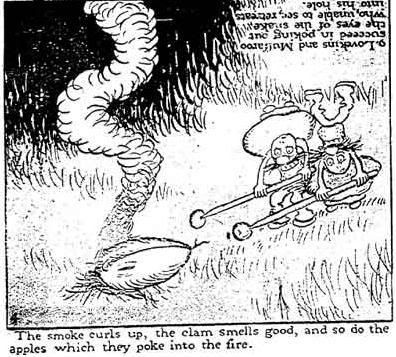

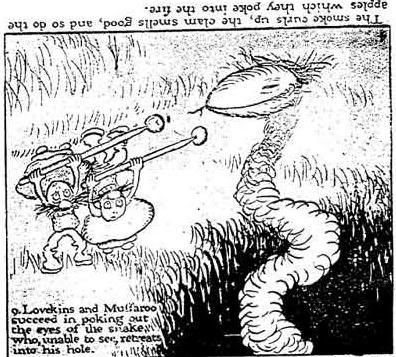

So, while in one direction you might see Lovekins and Muffaroo (a pair of storybook fantasy-type adventurers who appear to be living in sin, or in some mistress - sugar daddy arrangement) baking apples over a roasting clam...

...the other direction sees Our Heroes using pikes to rip the eyes out of a giant serpent that's risen from the abyss.

The effect is sometimes pretty dazzling, even at a reduced size, although Lovekins has always been a sticking point for me. That's not a hat, miss - that's a guy's legs. The trick is to focus right on her face, and try to forget a lot of her surroundings; Verbeek is pretty good with facial expressions, which goes a long way toward curing the awkwardness of his (highly ambitious!) concept. But that's not the sort of thing that registers unless you can see things really clearly, and you can only do that when the printing's very large. Which is to say, the size it was drawn to be read in.

How many other critical perspectives on older comics have been shaped by constrained perspectives? Isn't it a good artistic value to direct your work toward its mode of presentation? How many comics artists lost something across history due to changing standards? Under the assumption that 'bigger' only means 'more impact'? Books like this challenge such preconceptions.

4. Hungry Henrietta is Different From Just About Everything Else Winsor McCay Did, and Valuably So

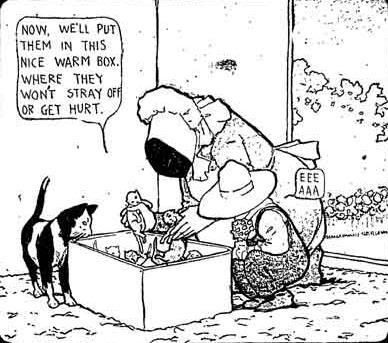

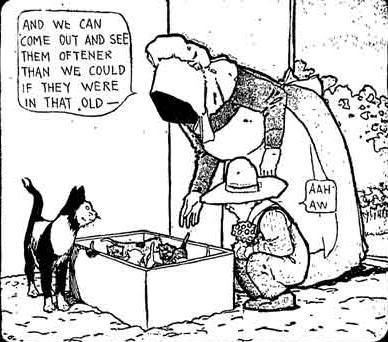

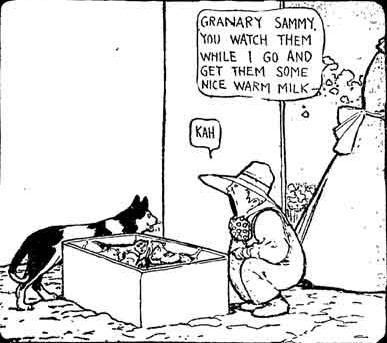

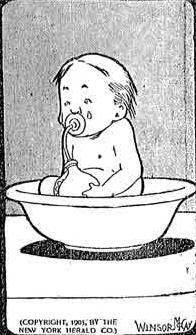

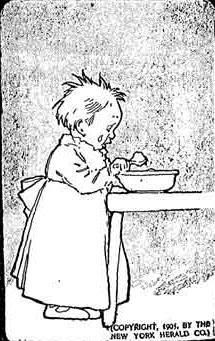

And then, there's The Story of Hungry Henrietta, the book's only sop toward the completest impulse. It's another McCay kid strip, this time an honest-to-god serial, presented (almost) weekly for 27 chapters, all of which are presented. The monochrome strip ran on the literal backside of the color Little Sammy Sneeze in 1905, and the two do act as companion pieces, in that the back work is also a one-joke strip about a kid with an odd ability: Henrietta, the protagonist, can eat. A lot.

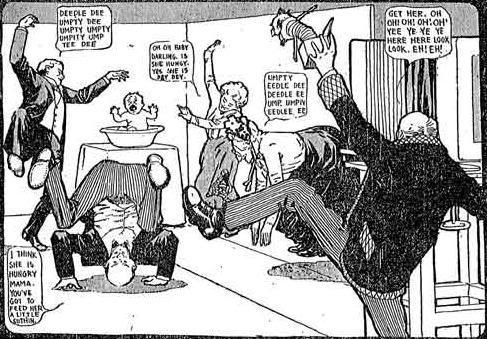

But there are many differences, astonishing ones. Henrietta's strip is no less than the chronicle of her life; she's three months old in Chapter One, and ages three months with every subsequent installment (as McCay is wont to point out in-strip over and over again). Henrietta doesn't seem to have any strange abilities at first - the early chapters are pure domestic satire, with McCay presenting the continuing antics of a clueless clan of upper-class folks who don't know how to calm their infant child. Often, their capering causes Baby Henrietta to cry, compounding their confusion.

So they feed her.

If Little Sammy Sneeze's humor is front-loaded in merely seeing what situation Sammy is up for ruining, The Story of Hungry Henrietta's is practically latent. If you've seen one strip, you've seriously gotten the 'joke' in full. Every episode trudges not merely toward an inevitable conclusion, but through an equally inevitable setup, with Henrietta's parents acting in exactly the same hopeless manner, toward the same end.

But then, a funny thing happens. As Henrietta grows, it gradually becomes apparent that her hunger has reached superhuman proportions. McCay begins isolating the child not only in a final panel of her eating, but in an opening panel of her seeking food. She eats a whole bowl of brandy sauce and gets silly. She devours fruit off a fancy hat. She rips into a beekeeper's equipment looking for honey, and gets stung. She even makes a color appearance in Sammy's strip, in which the boy sneezed a bowl of fudge into her face, and she picks it off and eats it right up. Her parents grow worried and disenchanted. Yet they can't cope. They're not prepared. She eats more.

By the time McCay is whipping up ominous panels of the angelic girl sitting shadowed in a cherry tree she's just been picking barren, the strip has wandered more into what's now called 'magical realism' than the knockabout comedy of Sammy. McCay does render the stories with his expected light touch, but there's a palpable undercurrent of sadness -- even horror -- to what's going on. And don't go expecting a resolution - Henrietta's story merely stops at age six and three quarters, despite the feeling that it's building toward something awful. Gosh, you think people didn't like it?

But even in 'incomplete complete' form, The Story of Hungry Henrietta draws attention to strengths that McCay is usually not known for. His human figure drawing, truth be told, is often rudimentary and lumpen, but the large size of this book reveals a keen command of Henrietta's body language, which communicates fear, cunning, shame, and the serenity of fullness, in lieu of many spoken words. McCay is also overtly satirical, as he would again be in his 1905-10 A Pilgrim's Progress, damningly criticizing the rearing mores of a class he belonged to. But he does it not only through gags, but cumulative build across many chapters, an eye-opening accomplishment for a man not well known for week-by-week pacing.

Maybe it goes even deeper. Despite her extravagant gorging, Henrietta never seems overly plump - McCay generally can't draw an attractive woman to save his life, but his Henrietta is always angelic in laying waste to foodstuffs. I suspect that's because the child is based on McCay's own daughter, much in the way a certain Nemo was based on his son. But then, what does that say about McCay, a well-off, famous success known for spending just as extravagantly as he earned? It could be that this story acts as self-critique as much as anything, giving form to lingering fears about raising a young child in the lap of luxury. And just as McCay's fantasies so often took terrifyingly large form, he could well have blown his personal concerns into a building Armageddon, with a gag-friendly touch.

I sure as hell don't know for sure. But the comic stands as perhaps McCay's darkest work, and a fitting compliment to his more famous strip in every way.

5. A Child's Life is Out of Control

Such is the greatest, if accidental benefit of this book - its simulation of 1905's reading style inadvertently throws a spotlight onto McCay's approach to his child protagonists. It's not the same approach every time - just as Sammy's body rages against the incomprehensible overload of the adult world in dazzlingly, surreal color, Henrietta grows into an unstoppable product of that same world's shortcomings in placid, slate tones. Let's not put too much emphasis on the colors -- after all, the Sammy strips not presented in this book saw an origin/return in monochrome too -- but we should remain appreciative of how they can flag McCay's portrayals of different aspects of a child's life.

I'd like to believe Sammy wouldn't hurt a fly, given his druthers, although McCay suggests that he's too young to have an internal life of note anyway. He instead reacts involuntarily in great, surreal, comedic waves, although we're left with the feeling that nobody is dreadfully harmed, and he'll maybe grow into a comprehending adult; whether that's triumph or tragedy is up to you. The scenes from his life are fit for the episodic format, as if bits of childhood fondly recalled, with each blast a different velocity to match the beloved situation.

But Henrietta is a child of serialization, and we therefore must accept the cumulative force of her ominous growth. She's as helpless as Sammy, but we can see the marks left on her by the adult world; her uncanny ability develops toward an endpoint we are not privy too. There is no indication that's she'll grow out of anything. Really, she'll grow in, her hunger growing larger and larger, with every unseen chapter. The indication is that we'll all see it soon enough.

What's even clearer, though, is the commonalities. Neither child is capable of taking their life entirely into their own hands... being children and all. McCay understands this helplessness, and recasts the fantastical humor of his young protagonists as reactions to adulthood, rather than actions toward adults. This portrayal of the world is also evident in the looming, shifting, unknowable spires and hues of another, far more famous serialized McCay work with a child hero, or even the temporary adult chaos of Dreams of a Rarebit Fiend, where all control is lost, all across the globe, for one night only.

Other, earlier strips were right in suggesting the mischievous potential of young children. But as authentic as literary characters as Buster Brown and the like might have been, they were still fashioned to the adult's perspective. McCay's nattering dialog suggests an understanding of adult ways, but his fantasy is primed as authentically childlike: helpless, curious, cradled, vulnerable.

The juxtapositions of this book, set down in natural size and authentic color, reveal these workings of McCay's. I wonder if those actual readers of 1905 made any subliminal note of these contrasts in their semi-similar morning papers. Well, this isn't a newspaper anyway. It's another worthy nugget from the Golden Age of today, an an especially edifying one through its construct. What relief! Like a bad sneeze fading into a lingering, cozy yawn.