My Life is Choked with Comics #13 - Black Jack

/![]() I may be some some east coast blue blood cracking my knuckles over doorbuster savings as I type, but out west at Savage Critic(s) headquarters it's still Thanksgiving, a beautiful all-American time for eating things and planning shopping trips for the next day.

Personally, I'm thankful for overconsumption every day of my life, so I'm never 100% sure as to why it needs its own holiday, but at least I'm sitting at my parents' house instead of my desk, and tapping out another installment of this lil' column. It takes a special column for this special day, so in the interests of keeping things 'in the spirit,' allow me to provide a short list of things I'm thankful for. Take my hand.

I may be some some east coast blue blood cracking my knuckles over doorbuster savings as I type, but out west at Savage Critic(s) headquarters it's still Thanksgiving, a beautiful all-American time for eating things and planning shopping trips for the next day.

Personally, I'm thankful for overconsumption every day of my life, so I'm never 100% sure as to why it needs its own holiday, but at least I'm sitting at my parents' house instead of my desk, and tapping out another installment of this lil' column. It takes a special column for this special day, so in the interests of keeping things 'in the spirit,' allow me to provide a short list of things I'm thankful for. Take my hand.

EIGHT THINGS I, JOSEPH S. "JOG" McCULLOCH, AM THANKFUL FOR ON THIS PROUD DAY OF DAYS (ACCORDING TO CERTAIN TIME ZONES OTHER THAN MY OWN):

1. Doctors

The threat of stomach pumping always looms on this bright American vacation day, so I figured it'd be good to talk about doctors. Who else will heal me from from my many imagined ailments? Licensed professionals, friends. When the chips are down, doctors can embody the very spirit of America.

But oh, that cranberry sauce has brought out my contrarian side, so my thoughts have drifted to the doctors of Japan. Two of them - one real, one fictional.

2. Osamu Tezuka

I trust most of you have heard of Dr. Tezuka. Truly one of the giants of world comics, Tezuka was a man of immense popular instinct, and creative prolificacy comparable to Winsor McCay. A brainy child of art-loving parents in the Japan of the early 20th century, Tezuka survived the onrushing militaristic thrust of his nation and the WWII bombings of Osaka to become a teenage comics superstar in the rubble of the late 1940s.

Obviously, there were popular manga artists before him, but Tezuka exerted an immense transformative influence on the form, blending irresistible narrative propulsion with a visual style inspired by the newspaper comics and animated films of the United States. His 1947 breakthrough in longform comics, New Treasure Island, all but jumped off the page via rigorous integration of cinematographic principles into the comics form.

He'd quickly calm down with the Ub Iwerks-style zooming, but I suspect it was valuable that manga became so immersed in cinema so quickly, in such a broad manner; these techniques quickly became internalized, acting as a core component of a growing comics idiom.

And Tezuka's achievement continued - his 1950-54 project Jungle Emperor Leo (aka, in anime form: Kimba the White Lion), a 600+ page cradle-to-grave account of an anthropomorphic hero in a world of animals and humans -- and not a female void in sight! -- brought popular renown to the longform magazine serial. In 1952, Tezuka introduced Tetsuwan Atom (Astro Boy), perhaps his most enduringly beloved work, a series of mostly standalone stories concerning a boy robot fighting for peace in a gleaming daydream of Japan's beautiful future, but not one incapable of cruelty. The very next year, Tezuka adopted a sprightly sparkle style for Princess Knight, a landmark work aimed at young girls. By 1963, Tezuka and his Mushi Productions had the Tetsuwan Atom television adaptation on the air, the first weekly anime series.

Sure, animators like Yoshinori Kanada were probably more responsible for the look and feel of 'anime' as we know it today, and manga has since gone through countless stylistic shifts, but Dr. Tezuka's powerful influence cannot be denied.

Oh yeah, he was licensed as a medical practitioner in 1952. It's been written that he rather liked the idea of becoming a doctor, a highly respectable social position, only to actually devote his life to the immeasurably less prestigious vocation of drawing comics.

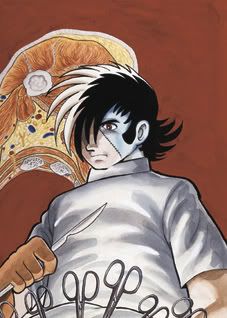

3. Black Jack

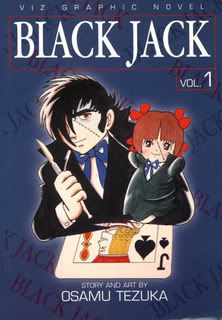

In 1973, Tezuka began to draw an episodic manga series about a doctor. It was called Black Jack, and it became another monster hit. The comic ran, in various forms, until 1984. A slew of adaptations, remakes and extensions followed, easily outliving Tezuka, who died in 1989.

In the autumn of 2008, Tezuka specialists Vertical Inc. will bring Tezuka's original manga to the English language. They won't be the first.

4. Ye Olde Books o' Manga

The story of manga publication in the United States is a rip-snorting one, the action-stacked details of which may kill the soft, but in the interests of post-feast digestion I'll only say that many false starts were made and format experiments pursued on the road to glory. One of the most prominent manga publishers today is VIZ Media, and its long history is littered with unfinished series and lost, unpopular items, going back to its late '80s biweekly pamphlet-format releases in association with Eclipse.

Prior to striking gold with its current monthly US edition of the mighty weekly anthology Shōnen Jump, VIZ made several other attempts at selling the primary serialization form of Japanese comics to North American readers. One of them was Manga Vizion, a mix of old and new(ish) series which ran from 1995-98. And from 1997 through the end of the magazine's life, Black Jack adventures were featured.

You can't say VIZ didn't try. Following the anthology's end, VIZ released two volumes of collected stories, one in 1998 and another in 1999. Compiling all of the Manga Vizion material with (I presume) a bunch of previously untranslated material, these books currently make up all US readers, at least, can read of the series in English.

I love hunting the phantoms of manga of in the US. The old, forgotten snatches of series. The bright efforts of days gone away. This will be the one. This one'll break us through. Manga is not beholden to the collector's market. The old books exist as used items, library castoffs and dusty bookstore lifers. They're often cheap; you need only find them, and study the many ways one comics "solitude," to steal Bart Beaty's term, tried to relate to another through days of bounty and famine.

I have Vol. 1 of the VIZ collected edition, and my perspective is duly warped by that exception.

5. Funnybook Fusion

To understand Black Jack is to understand a certain impulse of Tezuka's. In many of his works, he takes to tone like an inebriated teenager does a rented go-kart. That's not a complaint. Careful, building tragedy will inevitably deflate with a sudden pinprick of slapstick. Odd comedy will veer toward melodrama at the drop of a hat. Philosophy will mix with bullets pouring from Astro Boy's automaton ass. History is the stage for cold facts and pageantry in the Takarazuka Revue tradition.

This is the tenor of the man's most popular works. Some find it distractingly eccentric, but I see it as a vital component of Tezuka's charm - so many influences were embraced in his revolutionary style that he developed a supremely idiosyncratic method of communication, one that spoke to many thousands yet silently marked his work as forever his, even while many others adopted the mechanics of his style.

Black Jack is much the same, but with some added personal touches. The title character is a rogue, unlicensed surgeon, probably the greatest in the world. When he was young, he and his mother were caught in an awful explosion, and a doctor essentially sewed him back together, inspiring him to become the best in the world at healing others; a similar, albeit much less dramatic incident had inspired Tezuka's own interest in the medical profession. Much like the famed manga assassin character Golgo 13, Black Jack demands high sums for his efforts, and lives outside of polite society, but he fixes people to incredible degrees, often well past the boundaries of fantasy.

So, it's a little like an adventure, and a little like a superhero comic, but always boiling down to "Oh Black Jack, how will you medicine your way out of this one?"

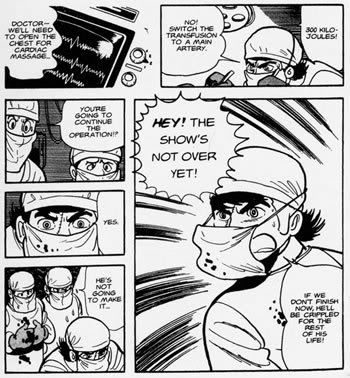

A fine illustration can be had with the origin story of Black Jack's sidekick, Pinoco, as included in the first VIZ book. Black Jack is woken in the dead of night to treat a masked female patient, a woman so prominent that none may know her identity for fear of scandal. Things look bleak - she's got a massive growth on her side, a most abnormal teratogenous cystoma. Her skeevy treating physician is a definite buzzkill:

"No hospital in the world is capable of performing this surgery!"

Still, none can match the unwavering skill of Black Jack. Even if the cystoma happens to be an undeveloped birth twin of the patient, lodged inside a rubbery membrane with a full compliment of vital organs. And psychic powers.

Yes, as any medical school in the industrial world will tell you, psychic powers can prove tricky on the operating table. Any surgeon that's so much as approached the cystoma has been taken with the urge to fling scalpels at nurses or smash bottles over their head in high slapstick form, until the OR is more a battlefield. Our Hero initially fares no better, wrapping a hose around his neck and holding his own scalpel to his throat, until he promises the sentient mass of parts to pull off a miracle procedure, and keep it alive.

Graphic, photorealist medical art ensues, slicing the story free from Tezuka's cartoon approach, then sewing it back on. Soon, Black Jack's got a heap of body stuff floating in a jar, and the patient's snooty entourage can't wait to be rid of it. Alone in his lab, Black Jack stares at the jar, pours himself a stiff one, and sews the organs together inside a doll's plastic body, resulting in a small humanoid being that walks and talks and declares itself his wife.

One year later, the patient returns for a follow-up, and Black Jack introduces wee Pinoco (a doll brought to life, ya see), who immediately sets about kicking the shit out of her masked sister until Black Jack drags her off. "That brat couldn't possibly be my sister!!" declares the prominent woman, and her understandably agog aides drive her away, as Pinoco weeps against the doctor's leg.

If this sounds like a peculiar comic, rest assured - it is. But Tezuka's melange of style creates a bizarrely logical universe, as much through sheer force of will as advanced craft. In one panel, silhouettes of broad cartoon men emerge from a realistic ambulance, approaching the wavering, seemingly freehand-drawn Stately Black Jack Manor, a hazy sky behind them. In one page, Black Jack's eyes gleam like dinner plates from underneath his curvy surgical gear, as he brushes one of Pinoco's eyeballs with his glove. Two panels pass by, her realistic spew of organs ensconced in the stylized, anime-ready body seen above, the realistic vanishing into the fantastic.

That is the essence of Black Jack.

6. Lists Within Lists

Many other stories are included in that first VIZ book, each with a similarly berserk entertainment aesthetic.

- A rich man's wicked son rips himself to bits in an automobile accident. Black Jack is called in to save the lad, but he'll need a full-blown human body for replacement parts. Papa then musters a stirring command of citywide corruption, railroading a poor, innocent boy through the legal system as the responsible party for the wreck, getting him sentenced to death and spirited away to Black Jack's operating table. In possible violation of the Hippocratic Oath, Black Jack lets the shitty rich kid die and performs plastic surgery on the innocent boy so he looks just like the dead kid, then loads him and his mom up with cash so they can flee Japan. MORAL: Kill all decadent bourgeoisie, rise oppressed workers.

- Black Jack calls on a wealthy businessman whose life he saved to collect his fee. Since Black Jack operates outside the legal system, the monied man cackles and refuses to pay up. Were this a Golgo 13 story that'd be grounds for immediate neck-snapping, but Black Jack is a nice fellow who agrees to accompany the rich man and his buddies on a tour of his new impregnable airtight vault. A freak earthquake causes the door to lock with everyone inside, and Japan's lords of finance soil their slacks. Black Jack then makes everyone promise to pay him a hillion jillion yen to break them out, and his formidable skills allow him to find just the right part of the wall to cut through to get at crucial wires. Then everyone refuses to pay, but Black Jack still wins because he walks away proudly to let them stew in their moral shortcomings, just like that one story Steve Ditko did with The Question. MORAL: Fucking capitalist scumfuck shits.

- A young man is planning to leap to his death after bombing his high school entrance exams, but a passing day laborer gives him a good talking to. Then a gas pipe explodes and most of the laborer's limbs are blown off. Meanwhile, the fuzz have finally hauled Black Jack in for his wild outlaw healing ways, but he coerces them into letting him go in exchange for not letting people die (what a guy!). He then puts the laborer's arms and leg back on after remarking "Heh... usually I'd charge an arm and a leg for this kind of surgery..." Amazingly, further suicide attempts do not follow. Oh, and the boy learns the value of life, I guess. MORAL: Arms are really important.

- Black Jack is sent a scalpel in a mystery sheath by the doctor that saved his life lo those many years ago. After a journey, Black Jack arrives at the old man's bedside; he's dying, but he still needs to reveal the truth about the operation that saved Our Hero's life. Turns out he left a scalpel inside young Black Jack, and kept it a dark secret until he could operate again seven years later, at which point he found that the scalpel had been coated with calcium secretions, thus protecting Black Jack, and providing for a great mailbox surprise. All the medical skill in the world can't account for the mysteries of nature! Then the guy collapses and Black Jack totally fails to save him, because we are but mortals. MORAL: Death is inevitable, True Believers!

And that's just some of it. 7. Pumpkin Pie

I like pumpkin pie. It often tastes very good.

8. The Expansion of Vizion

I mean "some of it" not just in terms of other stories being in VIZ's book, or VIZ's other book, but in the Black Jack catalog as a whole.

So often, in dealing with foreign language comics, we act from a limited perspective. Blinders around our eyes.

For example, years ago, Tezuka could barely be known without consulting the Japanese originals or small excerpts in reference books. Later, bits and pieces of his works trickled into English. At that point, you could firmly believe that the mode of style I described above -- the comedy meeting melodrama meeting violence meeting philosophy -- was his sole signature, his whole way of being.

But Tezuka was so large. He created over 400 volumes of comics in his time. More and more came in, as manga became strong. More could be seen of Tezuka. The Dark Horse release of Astro Boy (their choice of title), showing both his range on children's comics and, yes, his reliance on formula. The Dark Horse release of early works like Lost World and Metropolis, clumsy, vigorous things redolent with still-congealing agony of influence. And Vertical's books. Apollo's Song, matching his love for education with a very '70s moral resignation. Ode to Kirihito and MW, seeing the master strip away elements of himself, to face the dramatic gekiga style that rose in response... well, to him. To what he represented.

Tezuka mutates. So does all manga. Perhaps as the current English-language audience grows, the predominant boy-and-girl comics of today's shelves will dissolve into the older-skewing manga that Japan has long ago grown for itself. A history in miniature. We won't need to hunt down the old editions for anything but history - no more constrained glimpses, like our Black Jack is.

He'll be back. Redone. Stronger, more whole. I'm thankful for that.

So mark down that late 2008 date, eh? Maybe next Thanksgiving I'll go over this stuff in a new way. I'll be equipped, and you can be too.

You wouldn't want him to be upset, would you?