I'm going to tell you some things I've thought about saying to several Americans, and various foreigners too: And I didn't think I'd get the chance

/![]() The Winter Men Winter Special

The Winter Men Winter Special

God, The Winter Men. Where did this thing start publishing? Atlas/Seaboard? Was issue #1 published on the date of my birth? Be this my destiny to write a spoiler-packed internet review of the final issue? Is this really the final issue? Two and a quarter years after the last one?

I mean, that's pretty remarkable. That it's here, I mean. A lot of things happen in 27 months - plans change, publishers shift gears. The WildStorm of 2009 is very different from the WildStorm of 2006, far less inclined toward supporting a self-contained quasi-superhero book, or really much of anything that isn't a shared-universe title or some media tie-in thing. Oddly enough, one of the few exceptions has been the 2007-08 Peter Milligan/C.P. Smith series The Programme, which dealt with the deadly return of a hidden legacy from the Cold War, much like The Winter Men, although all 12 of its issues were released within the gap between this Winter Special and its direct predecessor.

But at least the new comic is here. And 40 pages long! With no ads! A real ending, just as promised! It's a rare thing for a seemingly dead series to even get such a chance, and rarer yet that it's not only VERY GOOD, and a very logical, satisfying part of a whole, but oddly contemporary too, as if it somehow had to show up in 2009, even as it bears the marks of earlier times. Doesn't the 'Winter Special' designation seems like a wink at the old seasonal specials WildStorm used to run every so often? Actually, the Wildstorm Winter Special came out in late 2004, back when this series was still cooking, though not yet published.

Here, let me explain.

As far as public knowledge goes, The Winter Men was initially intended as an eight-issue Vertigo miniseries. The creators were writer Brett Lewis -- best known at the time for his contributions to Bulletproof Monk, a 1998-99 Flypaper Press production for Image that later got adapted into a movie, albeit without credit to the comic's working-for-hire creative team (which also included artist Michael Avon Oeming) -- and artist John Paul Leon, working in collaboration with colorist Dave Stewart and letterer John Workman. A two-page sample of the upcoming miniseries appeared in the April 2003 Vertigo X Anniversary Preview, a promotional pamphlet that the reader was given the privilege of paying 99 cents for; neither Stewart nor Workman were credited in that excerpt, and both the colors and letters would change when the pages later appeared in the series proper.

And as it went, those two pages were the only Winter Men material actually published by Vertigo; by the time issue #1 appeared in August 2005, the series had become part of the short-lived WildStorm Signature Series line of creator-owned works (with DC Comics retaining the applicable trademarks), although Vertigo senior editor Will Dennis shared an editing credit with WildStorm's Alex Sinclair on issues #1 and #2, suggesting that the switchover came a good ways into production.

(tangentally, the Vertigo X preview also featured coverage of another famously troubled work, Garth Ennis' & Steve Dillon's perpetually forthcoming 'literary' comics opus City Lights - "there's no stopping us now," declared Ennis, inaccurately)

When it eventually arrived -- and I'll confess I only picked that first issue up when I heard people enthusing about it online -- The Winter Men already seemed a bit like something from years earlier, a 'superhero' comic wherein the superhero elements were pushed as far to the back as possible, as was the trend among several of Marvel's early 21st century projects under the tenure of president Bill Jemas.

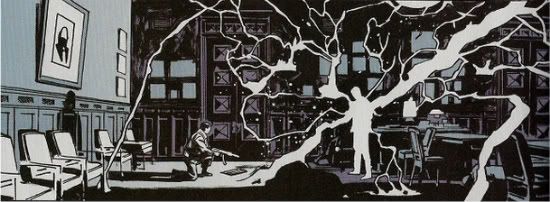

Yet it sure didn't read like a Marvel comic of that time, or 2005 for that matter - loaded with narration and labels and dialogue and tight, buzzing panels, the first issue seemed the very antithesis of decompressed 'widescreen' comics, with Leon's modulated linework (thick 'n inky up close, scratchily cartooned in longview) blending with Stewart's muted palette and solid hues to create a tone more akin to some handsomely understated European album than nearly any North American super-comic. The plot was both intricate and enigmatic; Lewis' density of scripting focused mainly on detailed scenes redolant with offhanded cultural references and carefully metered dialogue, as if to evoke a very intuitive translation of something originally in Russian. Bits of story progression were sometimes only sprinkled among chit-chat about the Moscow power grid or the web structure of Russian organized crime.

The primary narrator and key anti-hero was Kris, a former Spetsnaz man and self-styled poet who was once a member of Red-11, a Soviet-originated team of specialists clad in flying armored suits, nominally for use in dangerous missions but really to act as a check against the nation's potentially dangerous superhuman program, which was centered around a near-legenday propoganda figure known as the Hammer of the Revolution. All of these competing forces were known collectively as the Winter Men, even as they were tasked by design with destroying one another for power's or suppression's sake - draw your own USSR metaphor.

But it wasn't superhumans that killed the Red-11 squad. They suffered a crushing defeat in Chechnya -- presumably the First Chechen War, with all accordant symbolism as per the troubles of the post-Soviet Russia -- and the haunted Kris was left a man between useful seasons, doing odd, dirty jobs for judges and the mayor of Moscow. This frozen state led him to a confrontation with Drost, a lifelong soldier for something or another and a fellow ex-Red-11, who agreed to swap a quick resolution to a nagging criminal-political matter (in the series' privatized Moscow, a free-for-all among rival gangs and governmental bodies, crime and politics are pretty much the same thing) for a no-win murder/kidnapping case involving a young girl who got a black-market liver transplant from what turned out to be a Very Special Source: a potential superhuman.

Needless to say, the plot then spread to include approximately half the population of northern Eurasia, with a special emphasis on three of Kris' four surviving Red-11 teammates: Drost, the aforementioned soldier; Nikki, the gangster; and Nina, the bodyguard. A mystery teammate known only as "the Siberian" remained off-page.

Kris travelled to America to infiltrate the Russian mob and crack its organ trade. He faced off with the CIA, and raised an army in Western Asia with a handful of money. He murdered trusting friends in cold blood, got lambasted for never moving forward, got a mafiya tattoo urging him (specifically his fist) to move forward, and never saw his wife leave him. Hell, he even rescued the little girl at the end of issue #3, although it soon became clear that the saga was far from over.

All the while, writer Lewis structured each issue as a discreet unit, with each chapter's action broken off from the others by time's passage and shifts in location (hardly a trait of decompressed superhero comics!). And even within each issue, small segments would bump Kris forward in time -- months and months pass in issue #2's America alone -- as his narration doled out pertinant trivia and background information. Often, while sinking deeper and deeper into the international conspiracy, Kris would opine as to the obsessive-compulsive nature of the old Soviet intelligence, never prone to allowing for coincidence - it sometimes came off as Lewis trying to cover for his less tenable plot contortions, just as all that lived-in detail occasionally seemed like heavy research getting plopped onto the page.

Also in issue #3, as he waited to brief CIA operatives on his mission, Kris mused that "I'll have to leave out some small other things too -- and with what's left -- the story becomes difficult." That later became very important.

Issue #4 of the series didn't arrive until April 2006. Scott Dunbier had become the editor, and suddenly, according to the cover, the miniseries was only going to be six issues. All that despite the issue itself posing as an Interlude (one suspects for the halfway mark), focused on Kris & Nikki driving around town, picking up protection money, restoring citizens' power, discussing the plot, drinking heavily with strangers and shooting a man in the head at the behest of a local judge.

I think that was when I realized that the series was truly something, a crime comic matched perfectly with a vividly drawn foreign locale, and warm and authentic friendships (and very crisp dialogue) contrasted harshly with moments of amoral cruelty, the former informing the tolerance of the latter. The superhero content acted as strict, potent metaphor, the dangerous days of a world superpower recalled with wonder and fear, and the people left scrambling for dangerous shards of that old Communist power in a post-super world, after the big times ended. Even the romantic/terrible grit of lawless Moscow was real enough to work; when Nikki the gangster mentions good times of dealing in Ninja Turtle toys, it brings to mind that old interview Kevin Eastman did with The Comics Journal (issue #202; read it here), in which he mentions signing with a Turtles sub-licensing agent and possible gangster on a deal to truck toys into Russia - the copyright/trademark would be defended with his fists.

Then the series vanished for a while. Issue #5 landed in October, its solicitation announcing that there'd be eight issues again, and its final page happily noting that it was the final regular issue, with a special edition forthcoming to resolve everything. Plot points were hustled through with considerable speed; some content promised in issue #4's Next Issue box simply didn't appear. Hints and suggestions appeared. "Your endgame is rushed," an elderly architect noted to Kris, who later ended the issue's narration with an even more telling line: "And wouldn't that have been a good ending?"

Do you think?

So this is the real, 100% authentic final issue of The Winter Men, may it trade and multiply forever, and I think it's safe to declare it a choice example of 'supercompression' in North American comics, akin to Casanova and the later, crazier bits of Seven Soldiers in poise (if not tone). There may be two issues' worth of space in this comic, but Lewis packs in three or four issues worth of stuff; that doesn't quite make up the difference, mind you, since the each issue of the series typically included the stuff of two, but it's still noteworthy.

The supercompression approach serves both creators well. Leon -- still with letterer Workman, although frequent collaborator Melissa Edwards has replaced colorist Stewart, to a slightly washed-out effect -- is perfectly adept at packing small panels with minutely-carved detail, while Lewis builds upon the self-aware and 'self-contained' style of earlier issues to advance the plot forcefully in the same bursts of action that marked earlier issues, although this time (probably) to the effect of leaping over material he can't otherwise hit from space constraints. As a result, the series reads shockingly well as a whole, given the endless problems it encountered during production. Not to mention its narrator's tendancy to say things like "I will just tell you the good parts..." - hey, it's just Kris being Kris by now.

It's not just plot-plot-plot either. Actually, I'd suggest that a trait of the supercompressed comic (among straightforward genre works, at least) is that it doesn't just stuff in shitloads of plot, but layers on digressions and backstory and flavor, as a means of making the work especially rich. I don't think there was any particular need for Kris to enjoy a two-page sexual idyll with his separated wife, but I'm extremely glad it's there for the dimension it adds to Kris' character, which Lewis then cannily exploits three pages later when Our Hero cuffs a girlfriend in the face to scare her away from the dangerous life of the Red-11.

There's also a sudden resurgence in the fantastical elements of the story, with a trip to a 'former' Gulag featuring a flame-spewing cyborg guard, and a train ride to Siberia seeing Kris & Nina facing off with a flying armored suit, itself prompting a flashback to the Red-11 calamity in Chechnya and some awesomely clunky mecha designs. Granted, the dark secret of Kris' trauma turns out to be somewhat pat -- he was once in love with Nina, but left her for another female teammate who died when Kris froze, maybe due to equipment malfunction, maybe due to sheer stupid terror -- but it does explain why Nina is so lightly characterized compared to Drost & Nikki. This is Kris' story, told by him, and subject to his edits and biases, and he adores Nina as a perfect element of a happy, lost past; there's a fight sequence in issue #5 where Nina kills the hell out of oncoming forces and Kris' narration just stops for a full page until she's done and she gazes straight at the reader in close-up and Kris simply declares "Nina -- the barricade girl." And it all becomes so weirdly romantic the second time through.

The Siberian also comes into play this issue, probably the most bloodied from the series' abridgement. You can all but see his journey from the Gulag to civilization doled out through issues #6 and #7 (or maybe some earlier version of issue #5, since issue #4's Next Issue thing promised his involvement), building him up as a consummate badass armed with info that even his teammates aren't aware of, and noting his secret connection to the man behind the whole crazy affair, the chessmaster moving the pieces. As it stands he remains something of a puzzle, if given exactly the detail needed to explain his motivation for taking on the Hammer of the Revolution.

That's right. Lewis eventually reveals that the Hammer, the legend himself, was behind the whole deal, scheming extravagently to erase any weapon that might kill him, and hopefully getting different weapons to destroy one another. He's quite a charged figure, blue and glowing in his true form as an obvious evocation of a certain temporary anti-Communist from another DC-released comic book; the timing couldn't be better!

But Lewis' marvel of science isn't nearly as prone to transcendence. He's like the glowering spirit of revolutionary impulse, his origin tied to the Tunguska event of 1908, so close in proximity to the 1905 Russian Revolution. Stalin couldn't control him, though, so the Soviet state roiled itself into finding ways to both mimic him and counter him, creating a mad rush of competing interests that eventually broke down totally into the web of gross desires that runs the streets.

He tells Kris of the collapsar -- a notion first brought up by a schemer in issue #3 -- where both of them are, chess pieces on the same space, superman and rocket man set by politics to erase one another, somehow despite the collapse of the State itself. Revolution Means a Circle, as the issue's title proclaims, and it does seem that nobody, least of all Kris, has moved forward. Need I mention that the Hammer was posing in the mayor's office as an architect -- amusingly, the same one that delivered the above-mentioned line alluding to the series' lack of space -- whom Kris once told to 'go build something,' that very wish repeated with a different connotation as part of this issue's all-action climax? The promise of a beautiful, revolutionary future spoiled?

Everything seems inevitable by the end, as if there really aren't any coincidences. The Hammer was present in issue #1, in disguise. Reading the series over again, I noticed all sorts of little hidden aspects, like a traitorous gangster character from issue #3 hanging around in the background of issue #2, or little hints that Kris' girlfriend is going to begin an affair with Nikki. In issue #4, Nikki is already showing Kris bits of the Winter tech he'll use in the endgame. The Hammer is eventually brought to his knees by Drost, the man who was supposed to head the whole damned investigation to begin with before he traded off with Kris at the top of the first issue.

Through it all, some flaws remain evident - for all its oft-stated claims of being unlike your typical Western action tale (yeah, like everything, that's mentioned in-story), the whole thing does build to the old-as-the-hills trope of the (sympathetic) villain offering the (anti-)hero the chance to work with him and Our Man turning him down to set up the final throwdown. Which leads to another problem, one common to supercompressed works - the action just doesn't have a lot of room to build up power on its own, so three pages of Kris strapping on a cobbled-together approximation of the ol' armor to fulfill his purpose seems less mighty than pat from lack of space, like it's something he just had to do to gild the circular lily.

Yet, in the end, The Winter Men is about people and a society going in circles; its title refers to competing, mutually destructive forces crated for the 'good' of a state, and its depiction of Russia is full of the echos of a lost superpower, and most of its poorer traits as made even worse. From there comes the crime and the mystery. Good thing it's a strong, well-made genre piece, deeply clever and strangely immediate, given its own life of struggles. At least something moved forward to a conclusion! It even has the cheek to nod in the direction of a sequel, so maybe a Winter Men Spring Spectacular will show up in 2012, along with Big Numbers #3 and City Lights #1. If I can go by what's here, it'll seem like no time has passed at all, its heavy approach given the tenor of good conversation and a keen sense of skipping around and honing in on what's important. Like Kris says:

"...and it is what you leave out that makes the story."