I will now adopt the Diamond perspective: That's how this is 2/13

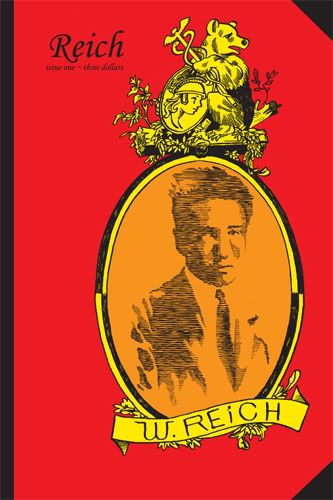

/![]() Reich #1:

Reich #1:

Here's an increasingly rare sight in the contemporary Direct Market: a new, serious, pamphlet-format 'alternative' comic from a comparatively small publisher, determined to serialize a single, long story over an indeterminate number of issues, to be released at a regular, quarterly pace, in probable anticipation of a collected edition to follow. Truly, Sparkplug Comic Books is appreciative of the old-time aesthetic!

Ah, but we must check our viewpoint against the realities of today. First off, this is not a new comic. It's new to most comics shops because Diamond, to the best of my knowledge, has just gotten to distributing the series. There's already two further issues out from the publisher. Moreover, writer/artist Elijah J. Brubaker has been working the series subject matter at least as far back as a 1995 minicomic of the same title, and had been releasing the present series' content as a webcomic until recently. And as I guessed above, I doubt this will be the material's final form.

Anyway, Reich is a comics biography of Wilhelm Reich, the infamous Austrian-American psychiatrist/psychoanalyst best remembered today for his development of orgone theory, and eventual imprisonment for failure to comply with a court injunction mandating the destruction of orgone therapy equipment and literature. Brubaker notes in his introduction to this issue that most perspectives on Reich trade on his counterculture value or fixate on aspects of the man's science; in contrast, this comic is set to present a take on the humanity of Reich.

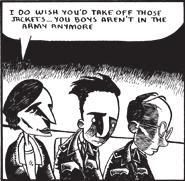

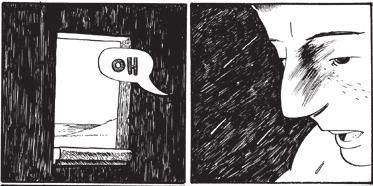

It's also, by Brubaker's admission, "indebted" to Chester Brown's 1999-2003 comic book biography project Louis Riel (from Drawn and Quarterly; now collected), adopting both the simplicity of Brown's visual storytelling -- not one of this comic's 24 b&w pages breaks from a six-panel grid -- and his proclivity for backmatter annotations. Unlike Brown's squat, Harold Gray-influenced artwork, however, Brubaker pursues an oddly three-dimensional arrangement of big-headed stylized characters, their enormous noses casting deep, logical shadows on their faces. Character designs typically act as shorthand for everyone's internal state, although the artist also stretches, squashes or realistically details various heads when a specific, expressive effect is desired. In this way, emotions are known as constantly pliable.

It also gives off the sense of children playing around with Big Ideas; this issue sees Reich's awakening to orgastic potency in WWI, and his caddish romantic entanglements with young Social Democrats and pretty dilettantes in Vienna, while developing a passion for sexual analysis. Brubaker's story, while occasionally darting into diagrammatic illustration, or seeing characters narrate directly to the reader, mainly focuses on conversations between people across a flowing timeline. Politics seem little more than an excuse for fooling around, though Brubaker's Reich is doubly callous for adoring his theories of sex over living, sexual beings.

I wonder how the artist's visual style might impact Reich's later life; for now, for me, it seems to gently undercut the pretensions of youth; it also occasionally tumbles into obviousness, as with a panel of The Nasty Shadows cloaking Reich's face as he suggests an abortion for a poor girl he's impregnated, with awful results. I did find it GOOD on the whole, however, and would recommend it to those piqued by the subject matter.