Here's a few manga I liked (or sort of liked).

/![]() Although you should keep in mind that I'm the kind of guy who thinks the best publishing news of the whole San Diego con is that Pluto -- Naoki Urasawa's Ultimate Astro Boy!! -- will be coming to US shelves in February 2009. Granted, it's still an ongoing series in Japan (a somewhat irregular one to boot), and only up to Vol. 6 as of this week, so it's likely to hit a production wall around Spring 2010... but still, PLUTO!! And 20th Century Boys at the same time!

Although you should keep in mind that I'm the kind of guy who thinks the best publishing news of the whole San Diego con is that Pluto -- Naoki Urasawa's Ultimate Astro Boy!! -- will be coming to US shelves in February 2009. Granted, it's still an ongoing series in Japan (a somewhat irregular one to boot), and only up to Vol. 6 as of this week, so it's likely to hit a production wall around Spring 2010... but still, PLUTO!! And 20th Century Boys at the same time!

But here's some back-to-front funnies you can buy right now.

Real Vol. 1:

Oh is it? This one's gonna need some context.

The writer/artist of this thing is Takehiko Inoue, who is a full-blown manga superstar. I'm not using that last word lightly. His reputation was built on a 31-volume basketball manga titled Slam Dunk, which ran from 1990 to 1996; it was one of the most popular features in the most popular manga anthology in Japan, the mighty Weekly Shōnen Jump, which in those days had a circulation of well over five million copies, per week. It is credited with exploding interest in basketball among the youth of Japan; there is now a sports scholarship that bears its name.

After the series ended, Inoue became less interested in shōnen manga, those comics for boys. Following the 1997 release of a silly sci-fi basketball webcomic, Buzzer Beater, the artist devoted himself to seinen manga, those for 'mature' audiences. In 1999 he began a swordsman opus, Vagabond, which is currently up to its 28th collected volume. And in 2001 he started up a side-project, a seinen basketball story, one that's managed to pull together seven volumes so far as it creeps onward - and unlike those boy comics, this one is Real. See what I did there?

Ah, but old habits die hard. Or maybe manga editors are hesitant to break them. Whatever the case, there's no hiding that Real -- at least in this debut volume -- is a dead-straight shōnen formula piece, its story structure practically out of a table of forms in the rear of a manga textbook, all of it fancied up with scratches and grit and hard-livin' times. And I guess I can't blame Inoue and/or his editors for not wanting to start too far off from the stuff that made the artist a legend, but all the tropes and tricks have a way of bumping into the real stuff.

All your favorite character types are present. Nomiya is a hoops-crazy fellow with an awful afro, a total goof... with raw, burning talent inside. Togawa is a fiery young man with clenched fists... striving to be the very best at his chosen vocation. And sure, Nomiya is a goof partially because he dropped out of school following a motocycle accident that paralyzed the young woman he was trying to pick up, and Togawa is broodin in part due to the bone cancer that has him confined to a wheelchair, but it all rarely functions as more than an especially colorful means of pushing enemies toward extending the hand of friendship, raising a fist in honor of perseverance and guts, and celebrating sweat-soaked victory. And defeat... unto greater victory, one might expect!!

Now, I don't want to go over the top here. This isn't something like, say, Gantz (a fellow resident of the Weekly Young Jump seinen anthology), where the notion of maturity seems to extend exactly 0% farther than added gore and naked. No, Inoue does pepper his work with some nice, lived-in details, like the plight of playing basketball in a limited-space city, or the economic doom that faces kids that don't graduate school - I particularly liked the running joke about Japan's draconian, scammish system of driver licensing.

But then we get back to the courts, where Togawa's disability functions primarily to facilitate the burning of rubber and the blowing away of stunned opponents. I understand that Inoue is trying to build a nice message about overcoming life's troubles, but I don't think his character's shōnen heat is terribly effective in delivering it - as the rest of Togawa's wheelchair basketball team grins over a loss, settled comfy into their positions ("I mean, what do you expect? We're disabled."), Our Hero lashes out with his fists, knowing that the path to Real fulfillment is that of a thousand boxers and bread bakers and martial arts winners in comics of the past, and thus his body's state is little more than a crucible for cooking up outstanding moves.

It's not that I'm at-heart opposed to boy's manga structures acting in an allegorical manner, mind you, but it all does have a way of making Inoue's pretensions toward grit seem... well, pretentious. And, about 3/4 of the way through this book, it's suddenly as if someone realizes the latent problems in interfacing with realistic disabilities on the plane of ninja superpowers, and the story launches into a detailed, fairly effective portrayal of coping with serious physical problems, one that unfortunately comes barreling into the story through a whopper of a plot contrivance. Still, it leaves one hopeful that Inoue will look a bit deeper than easy, friendly old motifs as the story goes on - it's only volume one, after all.

So, er, why is this a manga I (sort of) liked, as mentioned up top? Why is it still more-or-less OKAY? It all comes down to Inoue's visuals, at this point in his career a frighteningly assured evolution of the stylized shōnen realism of Tetsuo Hara (Fist of the North Star) and Tsukasa Hojo (City Hunter, on which Inoue apprenticed as an uncredited assistant), his sturdy figures powerful yet lithe, even a tiny bit feminine. VIZ's deluxe presentation preserves all of Inoue's delicate color sequences, which serve to add a dreamy texture to the rampant physicality. It goes without saying that the big basketball set pieces are flawlessly paced, mixing droplets of humor and observation into forward-rushing action, no movement less than perfectly clear.

You will understand how this artist got so huge (and, starting next month, you can directly observe his growth as VIZ rolls out Slam Dunk itself), even if you wonder where his art is going, so heavy with the shadow of past, youthful success.

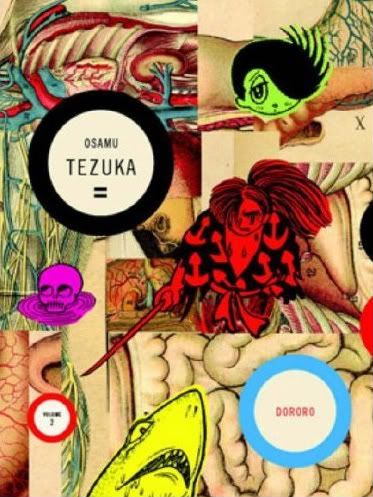

Dororo Vol. 2 (of 3):

Of course, some artists can mix things up more effectively than others.

For an unfinished 1967-68 series many anticipated to be little more than an appetizer before the great Osamu Tezuka's famed Black Jack -- coming later this year from Vertical, also publisher of this project -- Dororo has turned out to be a damned effective bit of work. It's got a formula too: every storyline sees driven, cursed Hyakkimaru and his thieving boy sidekick Dororo take on a fabulously nasty demon and The Inhumanity of Man, before getting chucked back out onto that long road. Hyakkimaru was born as little more than a human slug, his wicked father having traded 48 parts of his body to 48 demons before his birth, in exchange for Earthly power, but the boy's had himself augmented with a man-made humanoid frame, with swords under his fake arms and many other nasty tricks; it's no wonder he's made for killing, since every demon he slaughters wins him back another organic piece of himself.

It's a far wilder way to cope with one's disabilities, and that's only the bloody edge of Tezuka's berserk entertainment aesthetic, one that thinks nothing of following fourth wall-breaking zaniness with the graphic, on-panel execution of young children. Tezuka's style is not a realistic one, in terms of drawing or storytelling or whatever, though the story he's telling is often bracingly dark; rather, blood and gags flow naturally enough from his pen that all of this comic's setting seems a mad hallucination, cumulative in its burrow through the unconscious.

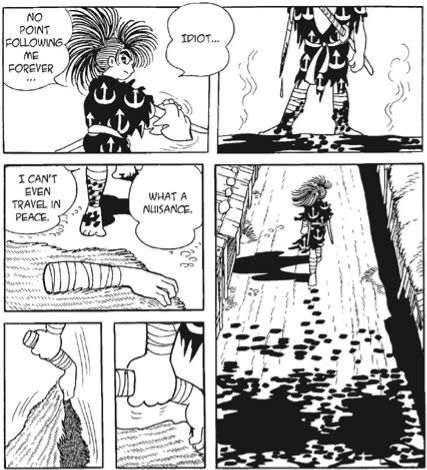

(this is actually from vol. 1, btw)

It's furiously good cartooning, pefectly complimenting Tezuka's tales of fox demons that inspire men to war so as to feed from the dead, and an evil god out to rip the faces from the faithful and wear them for vanity. A larger plot also begins to cohere, one I'm not sure will wrap up in a satisfying manner, given Tezuka's ultimate move away from the project, but the particulars remain VERY GOOD on their own.

(this is actually from vol. 1, btw)

It's furiously good cartooning, pefectly complimenting Tezuka's tales of fox demons that inspire men to war so as to feed from the dead, and an evil god out to rip the faces from the faithful and wear them for vanity. A larger plot also begins to cohere, one I'm not sure will wrap up in a satisfying manner, given Tezuka's ultimate move away from the project, but the particulars remain VERY GOOD on their own.