Finally: Manga you can put in your mouth

/![]() Oishinbo A la Carte Vol. 1: Japanese Cuisine

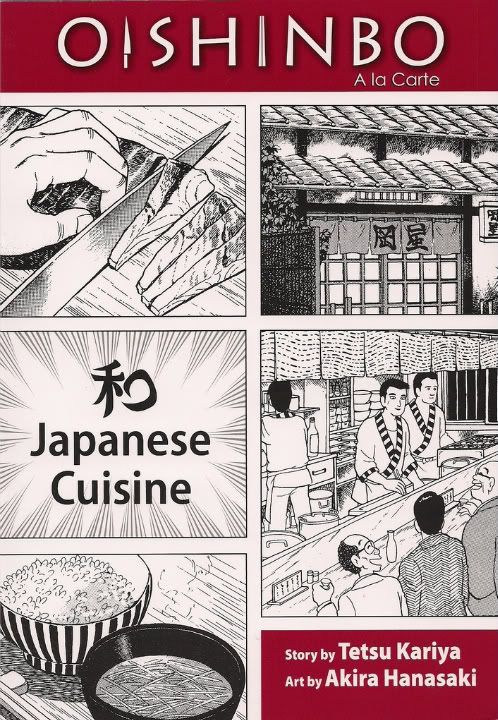

Oishinbo A la Carte Vol. 1: Japanese Cuisine

Yeah, you've heard it a hundred times by now: 'manga' as often seen in English -- a youth thing, a bookstore thing, a shōnen/shōjo thing -- is only a fragment of what manga really is. There's always a few non-porn exceptions, sure - most of them take the form of action or fantasy pieces For Mature Readers, with the occasional history of cup noodles or oddball art project slipping through. Astro Boy once filled us in on the story of Anne Frank, so there's always that. But it's still so hard to really get that old joke in Koji Aihara's & Kentaro Takekuma's brilliant satire, Even a Monkey Can Draw Manga, that one day there'd be manga for everything in Japan, up to and including train schedules. That's how omnipresent the stuff is.

So here's VIZ's latest exception, a 276-page, $12.99 peek into the secret world of mainstream manga for adults. And believe me when I say 'mainstream' - Oishinbo (The Gourmet) has been an ongoing series since 1983, and is currently up to vol. 102 (one hundred and two) in Japanese collections. Now, mind you, this English-language release isn't chronological or comprehensive; it's based on a separate Japanese repackaging, the A la Carte series, which itself has racked up 45 volumes since 2005 by sorting various stories from the series' run into themed collections. The very basic theme of this debut English volume (actually vol. 20 of the Japanese series) is Japanese Cuisine. Did I mention it's a comic about food?

Not that big a surprise, I guess - there's been a few English-translated manga involving chefs, your sheer shōnen Iron Wok Jan or the older teen shōjo of Antique Bakery. I've heard a few jokes about the sheer amount of food-related programming on Japanese television (including a 1988-92 Oishinbo anime, which ran for 136 episodes); Iron Chef apparently doesn't scratch the surface. So hey, why not some similar subject matter for an art form that's built up as much mass appeal as television? There's been golf manga and gambling manga, sex tips manga and religious cult manga - many with their own strata of legends, their masters of the form, heroes and inspirations little known outside of Japan.

Oishinbo is the work of writer Tetsu Kariya and artist Akira Hanasaki; neither have been published in English before, save for a few chapters of Oishinbo showcased in the semi-legendary 1990-97 'learn Japanese through comics' magazine Mangajin, although Kariya might also be known to my fellow obsessive compulsives as co-creator with Ryoichi Ikegami of the '70s schoolyard tough guys classic Otoko Gumi (Gallant Gang), which is supposedly more-or-less the ur-series behind Cromartie High School.

Hanasaki's visual style is a slick 'n staid approach that matches photorealistic (and, in all likelihood, photo-traced) backgrounds/items with the sort of airy, arch-mainstream cartoon character designs which, ironically, only ever seem to be glimpsed in North America through 'alternative' works that reference mainstream manga - think the pretty girl drawings in Hideo Azuma's Disappearance Diary, or the 'normal' framing sequence in Takashi Nemoto's Monster Men Bureiko Lullaby. It's certainly not very heavy on tilted panels or speed lines -- though both are present -- and may come off as oddly Western to some readers. Don't be fooled - it's just another aspect of manga!

The plot is the very essence of simplicity giving way to unlimited potential. Young Yamaoka Shirō is a newspaper reporter cum archetypal salaryman's fantasy character: frequently snoozing at his desk or plotting his next trip to the track, but always respected in the end for some superior attribute or another, here specifically an all but peerless taste in food pounded into him by his hated, brutal artist-foodie father, a man of such unflinching standards he worked Yamaoka's dear mother right into her grave and just didn't give a shit.

Now, Yamaoka has been ordered to assemble the "Ultimate Menu" for his paper's 100th anniversary, a quest that'll lead him to do basically nothing but enjoy hundreds of delicious, impossibly high-class meals all around the nation (just like real newspaper reporters!), while pushing him ever-closer into the arms of his lovely partner Kurita -- whom he'll eventually marry (this being a rather long assignment) -- and uncovering the occasional mild peril that's rarely more than one eating-related idea away from resolution. But watch out, Yamaoka - a rival paper is planning their own, cleverly titled "Supreme Menu," and they're staffed exclusively by sneering villains, and their project, dear reader, is headed by none other than Yamaoka's wicked father!!

Naturally it all comes down to consuming lots and lots of presumably expensive food -- money is almost never mentioned, as that would get in the way of the escapism -- in self-contained short stories roughly 25-30 pages in length. This VIZ edition is one of the nice ones with the flaps; it sports a pair of recipes and an extra-long translator's notes section as supplements, so you'll be double-damned sure you know the various cuts of tuna. The stories themselves are a little scattered, perhaps owing to this volume's vague theme, covering everything from rice preparation to sashimi slicing to the value of not smoking. There's stuff to learn, although I couldn't call it educational - most of the pieces are structured like little suspense thrillers, often pitting Yamaoka against his dad in battles of foodstuff wits that'll leave most readers horrified at the prospect of visiting Japan and subsequently being humiliated in public for wrapping rice in seaweed the wrong way.

But, you know, I found this book to be very interesting, not really because the stories are especially thrilling or impressive, or even for any reason directly related to food - no, I was fascinated by the comic's relationship with elitism.

Everything in this manga revolves around characters with incredibly developed taste, and every solution to every problem involves uncovering a superior presentation/preparation of food. Yamaoka may loathe his father, but he's hardly above correcting someone who's "enjoying" their food the wrong way, or standing up at a table to dismiss a meal as insufficient. This is no slobs vs. snobs saga - there's snooty antagonists that get taken down a peg, yes, but only because their hubris has somehow led them to advocate for something less than excellent. Sometimes Yamaoka is bested by his father -- any time Our Hero starts going on about gathering some showy arrangement of "the best" ingredients he's headed for a fall, since Japanese cooking is an unfailingly subtle art -- and while he scowls and pounds his fists it's always with some respect for how correct the old man is.

In other words, the series' stance can be summed up simply: it's best to be elitist, but try not to be too much of an asshole about it.

And you know what? Being an asshole is still better than being mediocre.

Gosh, that's not a sentiment you hear much of in North American comics. You can pick up traces of it in plenty of shōnen action titles - how many young men have raised their hands to the sky and vowed to be the very best there is? The cast of Oishinbo is a bit like that, if less childish - their Ultimate Menu quest is ultimately one of discovery, and even the worst setback, like, say, Yamaoka's father dismissing them all as unworthy to even dine in the presence of a truly great chef for getting their chopsticks an inch and a half too damp, only leads them to vow a greater level of achievement next time. As in, one character goes running off at the end of the story with a ruler, just to make sure.

Why is this? Is everyone mad? Is this a horror comic? Do I ever want to eat in front of other people again?

Quite simple, I think. At their bottom, these stories aren't just about eating or elitism - they're about patriotism. They're about discovering all aspects of Japanese cuisine, and drawing out the gorgeous simplicity and minute sympathies that make Japan itself a wonderful place, of wonderful, rich culture.

Do note the time when this series launched: 1983. The bubble economy was growing so much bigger, and Japan was getting noticed all over the world, especially in the United States. Oishinbo, aimed at older male readers, thus takes a position of intense pride, of showing how Japan deserves to be seen as excellent, to stand with the best.

One story sees a US senator of Japanese descent visit the old country; all the lush meals and local pomp mustered by bigwigs (as neat as it must seem for salaryman readers!) cannot compare to the gentle excellence of the best green tea, prepared beautifully in an aesthetically rich setting, "as if a breeze from a mountain stream has just blown through my body," the soul of Japan. Another sees a young girl raised in France ashamed of eating with chopsticks; she learns that the gentle caress of a meal is far less 'barbaric' than stabbing it with a metal skewer. A famed critic bloviates about the superiority of foreign procedures, but he goddamned learns some respect. And oh, you can just guess what happens when a crew of Benihana-style American-learned chefs-as-performers rolls out; it's not pretty.

Too bad that VIZ couldn't include some information on when these various and sundry stories were first published; I'd have liked to savor the subtle shifts in flavor after the bubble burst and Japan was reaffirmed as only human after all. But, fittingly, it would have to be subtle - there's no ferocious shifts in this taste, this cooking, this kind of mainstream. No, be quiet, and thereby be loud. Eat proud. Eat GOOD.