Comics!

/![]() (both from Viz, both $12.99)

(both from Viz, both $12.99)

***

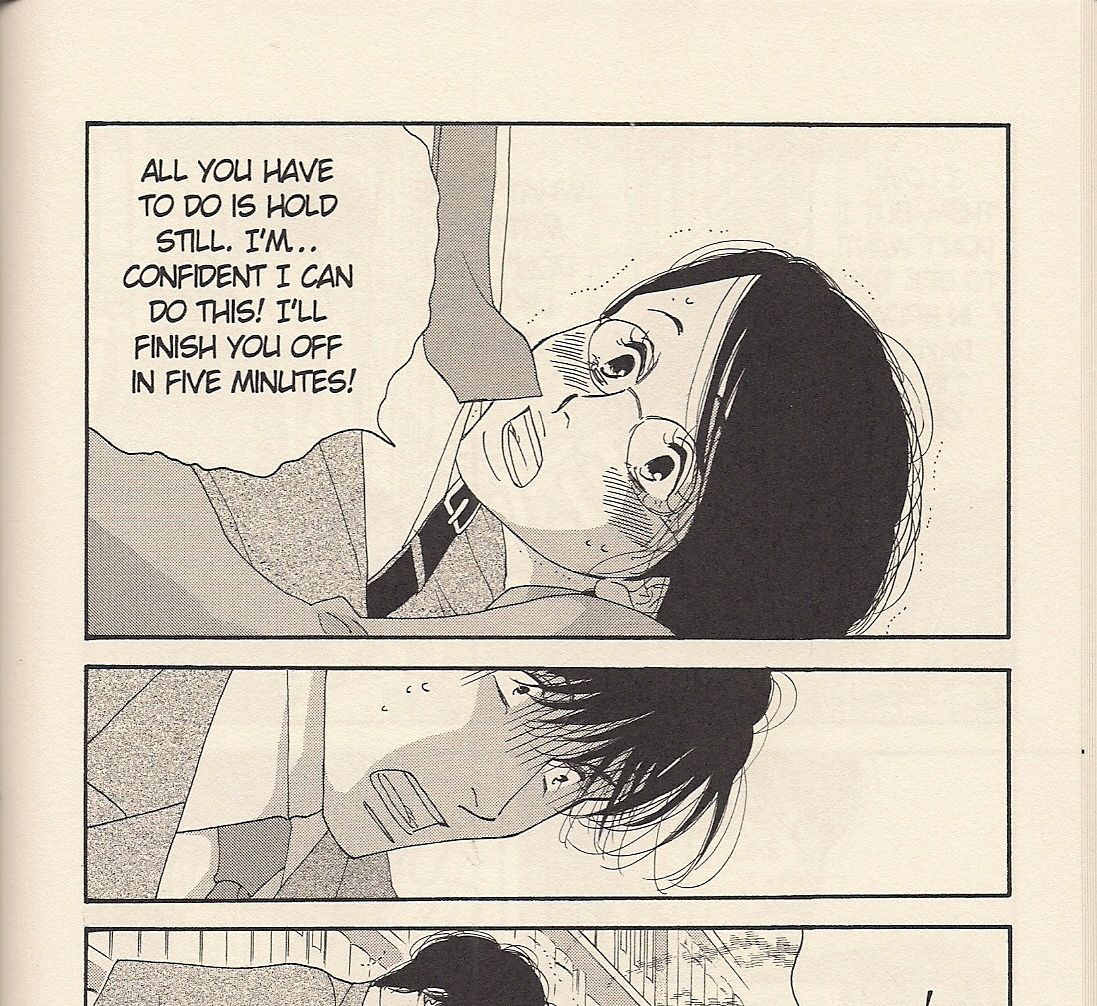

Biomega Vol. 1 (of 6):

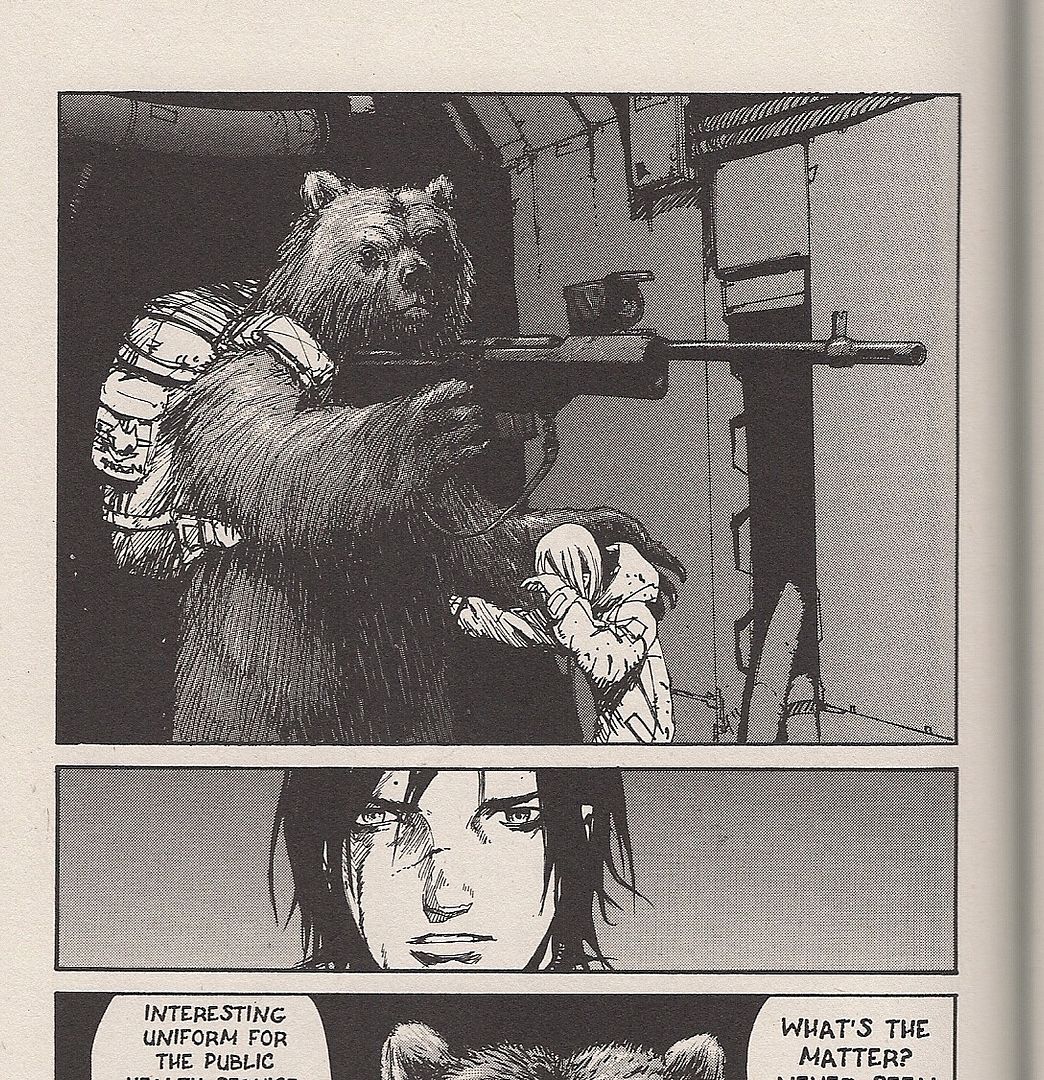

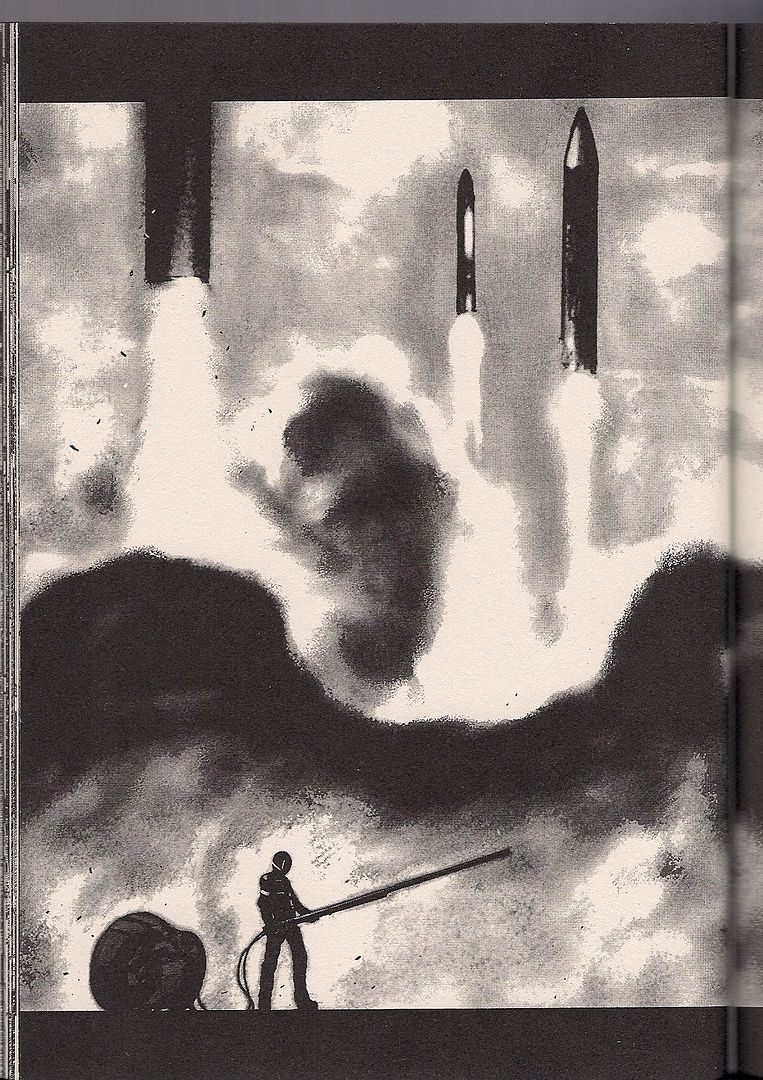

It's the 31st century and a virus from Mars is transforming everyone into mutant zombies; a synthetic human dressed in a black uniform and a black helmet rides his talking motorcycle at 666 km/h into a walled city on a mission to find a teenage girl, whom he almost immediately runs over as she crosses his path, tearing her leg most of the way off, only to have it heal herself in a manner perhaps expected of an Accommodator of the virus from Mars - the dazed girl, however, is also the ward of a talking bear with a rifle who shows up and whisks her away to a tall castle, wherein she is disguised in a bear costume which fails to bamboozle a Cenobite-looking villain with a bloody smock draped over a black cloak who defeats the talking bear and the synthetic human in combat and then stands on a ledge, the girl hoisted over his/her shoulder, shooting the castle with his gun until it explodes, albeit as the synthetic human rescues the talking bear, Kozlov L. Grebnev, who retreats to a submarine while Zoichi, the synthetic human, rides on his talking motorcycle, Fuyu, her AI materialized holographically as a woman in white, through a whole crowd of zombies, whacking at them with an axe en route to shooting the Cenobite-looking bloody smock villain in the head from a distance away while another Cenobite-looking villain in a gown of bandages loads the girl onto a shuttle, leaving her compatriot to mutate into a less human form and lecture Zoichi, who cuts him to pieces, on the villains' terrible plan to purge humanity forever and start a new race with the Accommodators, as emphasized by the sudden launch of thirteen intercontinental ballistic missiles -- while the talking bear watches television in a submarine and a newscaster shoots himself in the head because he cannot abide the baptism of the new society -- upon which Zoichi assembles a very long cannon from out the back of his talking motorcycle, somewhat in the manner of that very long gun the Joker pulls out of his pants in Tim Burton's Batman, and shoots all the missiles out of the air, a la the Batwing, as told to another black-uniformed rider, elsewhere, who fires his own wounded talking motorcycle's AI away in a rocket before confronting another Cenobite-looking villain in a trench coat with a gigantic sword who whacks him on his head, smooshing it all the way down between his shoulders, as the rocket evocatively clears the Earth's poisoned atmosphere into the dead silence of cool outer space. Comics.

Biomega is a big, loud, ridiculous heavy metal tractor pull of a comic, a nakedly derivative blood-on-black-leather action/sci-fi jamboree aimed squarely at 14-year old boys prone to drawing ninjas in class and 14-year old boys prone to drawing ninjas in class at heart. It's the kind of manga that mother (Studio Proteus) used to make (localize to English), and highly OKAY on that level, even if most of us can name a lot of recent zombie-dotted action/horror comics from out of North America; I've often found that manga iterations of such familiar material tend approach things with a notable lack of inhibition (see: talking bear w' rifle), and that's pretty much the prevailing virtue here.

Also, of course, there's the art of creator Tsutomu Nihei, whose 10-volume magnum opus Blame! (pronounced "BLAM" like a gunshot) was released by Tokyopop a few years back, along with an odds 'n ends 'prequel' book NOiSE, although he actually enjoyed the unique honor of a North American-specific color comics introduction prior to any of his Japanese manga seeing release, courtesy of the late Jemas Era out-of-print Marvel curio Wolverine: Snickt!, continuing the onomatopoeia theme.

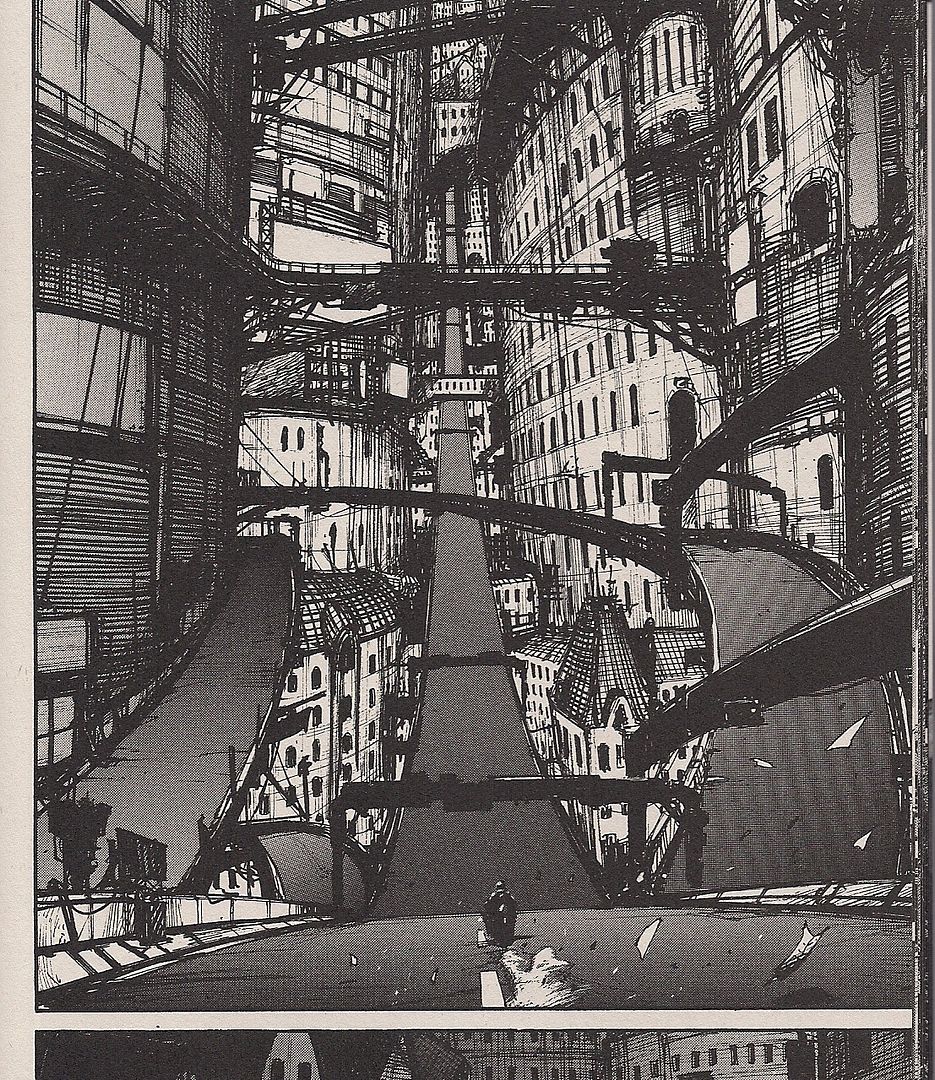

You might therefore conclude that Nihei is a man of lean, sleek action, but that's not quite right; a former architecture student and studio assistant to seinen suspense artist Tsutomu Takahashi (whose Ice Blade was among Tokyopop's early, unfinished translations), he's more 'François Schuiten reborn as an Image founder,' which isn't to say that his work looks like any of those artists' on the surface -- his settings owe more to the late Zdzisław Beksiński while his character art somewhat evokes Hiroaki Samura of Blade of the Immortal, comparisons which frankly do him no favors -- but that he practices a funnybook monumentalist approach reliant on the stillness of figures, be they looming man-made spires or detailed humanoid forms tense in action poses and thereby as awesome as skyscrapers.

So, yeah, it's more Cyberforce than Les Cités Obscures, despite Nihei drawing much influence from European sources; while Schuiten might reinforce the vulnerability of humans against massive mortar metaphors, Nihei explores the similarities of the two by rendering them both as cold structures -- with a few fuzzy talking anomalies -- coherent only in that they look as awesome as possible on every page, fully appropriate for his scenarios of humankind caught mid-transition into something new and less emotive, a theme sometimes attributed to other Japanese action stylists, like dubious anime legend Koichi Ohata of M.D. Geist and other bloody messes spattered over winning steel and augmented bones. Unlike many North American comics, which you can easily imagine spinning Biomega's man-against-many story as a fable of enduring individuality, this one explicitly casts its hero and villains as representatives of unseen organizations, literally built to order. The sociologists might have more to say on that.

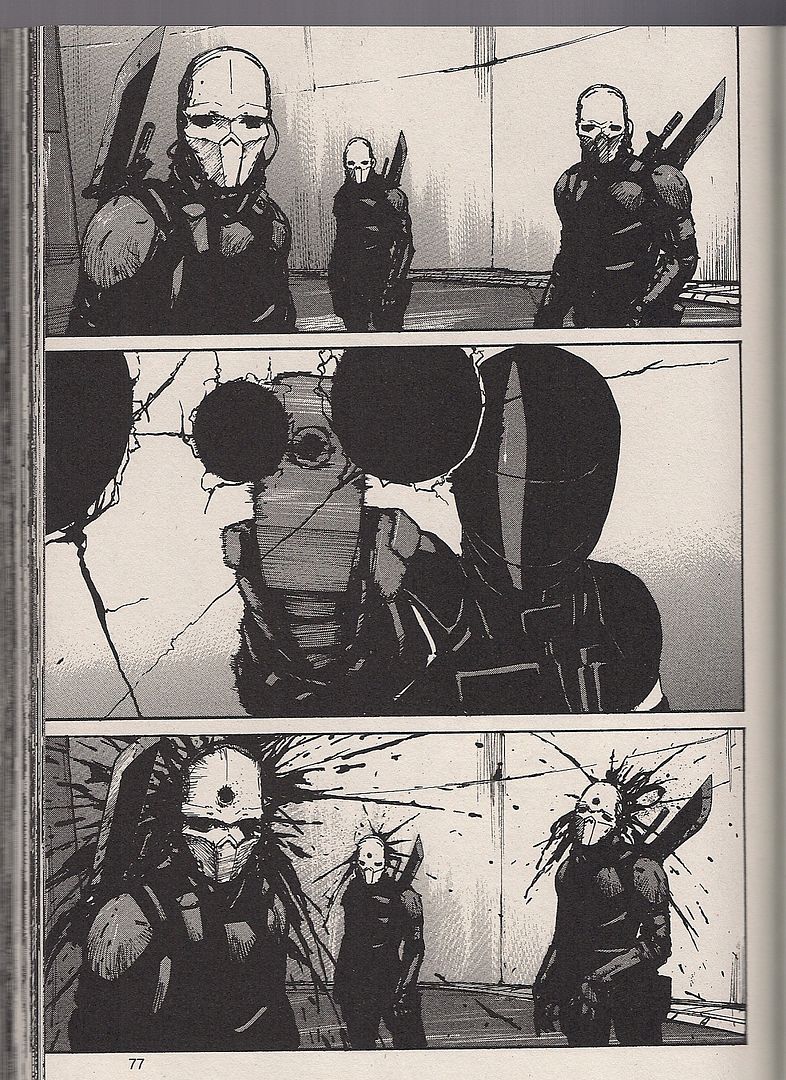

This points to Nihei's faults as well. His plots tend to be exceedingly basic, elaborated upon mainly to throw obstacles in front of characters prone to coughing expository matter into each other's faces when they open their mouths, which is not often. Nihei demonstrates little command of body language, and seems disinterested in the niceties of facial expression. Moreover, he's largely inapt at conveying physical contact between panel elements, which, all visual-thematic analysis notwithstanding, is kind of a problem for an action comic that boils down to Kamen Rider Vs. the Zombies; that early bit with the talking motorcycle running down the heroine is so lacking in visceral impact its huge overcompensating WHUMP sound effect -- admittedly a publisher's addition, but I tend to presume these things roughly match the Japanese sfx elements -- comes off as simply funny.

What makes this more worrisome is that Biomega is a newer work (serialized 2004-09), and seemingly intended as a more directly engaging piece; say what you will about Jim Lee, but when, say, All Star Batman kicks All Star Corrupt Police Officer in the face, you can fucking feel it. Little of that comes through in Nihei's art, and I do get the impression he's keenly aware of it - a later bit with the Cenobite smock villain winging a punch off of Zoichi's helmet sees the entire point of impact covered by a helpful shower of sparks. Likewise, virtually all of the big action sequences are powered by fairly clever shifts in perspective, like a close-up panel of a character firing a rocket -- and speaking of stillness, Nihei is extremely fond of stroboscope-like images of projectiles frozen in mid-air having juuuust exited the barrel of a weapon -- followed by an over-the-shoulder glimpse of the target with the prior character now in the background, the rocket halfway between them. All posed, all tense.

An interesting effect sometimes results, circumstantial evidence of the artist thinking his limitations through. Zoichi is a very fast character, even without his talking motorcycle, much faster than most of his opponents. Nihei will sometimes use good ol' speed lines to convey this, but other times, without warning, he'll lay out a series of panels depicting Zoichi performing some activity grossly out of synch with everyone else around him, so that he'll nonchalantly draw his gun and calmly point and fire at everyone's head while other characters spend every panel in either exactly the same pose or some barely-along variant of such, save for their heads erupting. Their bodies will still be in mid-fall as Zoichi prepares to leave, and then the in-panel action will snap back into synch. A very cool effect, and I mean 'cool' as in disaffected, and neatly facilitated by stiff, posey characters.

He can't do that all the time, so, despite his rough, scratchy lines, some pages replicate the detached feel of slick, heavy realist superhero artists, though Nihei is closer to Jae Lee's intense reliance on mise-en-scène then overt ships-passing-in-broad-daylight chaos. From this, the artist taps his greatest effect - the sense of place that admirers tend to cite. That's not just in background drawings; David Welsh recently compared Biomega's overall style to that of a first-person shooter -- and indeed, Nihei is supposedly an avid Halo player, preceding his contribution to The Halo Graphic Novel -- but it struck me as more of a 3D action platformer, where the fighting is often secondary to exploring landscapes, just being there, although you can't really advance without fights.

In this way, the key problem with this first volume is that it's an awfully event-heavy play-through, a straight shot, I guess more of a 'proper' crazy uninhibited action manga, from an artist that's defined by his visual/tonal departures from the norm.

But the oddest clash in this book isn't so visual. Keep in mind: when I say the story is "uninhibited," I don't mean it's something like Hiroya Oku's Gantz, which is so po-faced skintight sleazy it borders on camp; in fact, Nihei's body of work is notable in being almost totally without overt sexuality, to the point where I was surprised to learn that his official art book has 'erotic' pages. To my eyes, Nihei's depiction of bodies implies reproduction as a mechanical operation, an act of necessity in appropriate circumstances, as suggested by Blame!'s particular transhuman blend.

Even though I look at the villains in this book and think "Cenobites," Clive Barker's creations tend to be very specifically sexual beings; with Nihei, the surface is adapted into a larger asexual aesthetic. H.R. Giger is another popular point of visual reference, but his fetishistic aspect is diluted into people-as-buildings-as-society totality. Certainly there's no superhero mega-cleavage or male manga fanservice, although the perpetually dazed, childlike 17-year old at the heart of Zoichi's quest showcases several prominent traits of the helpless, hapless, tragic moe girl, which makes for a hilarious, brilliant, and almost certainly unintentional illustration of exactly how little this character type differs from the damsel-in-distress stock of the most clichéd, retrograde macho man heroic fantasies imaginable in genre fiction.

I wonder if that kind of stuff was added to this book to make it more 'appealing' to a wider audience? The back cover and the color front section are decorated with the image of a zombie woman in low-riding bikini bottoms. My problem isn't these images on their own, or Nihei's sexless style, but how badly they jar, like a (possibly editorial) grandmother sitting down with a boy who'd rather play video games than talk about girls and awkwardly inquiring as to his favorite actresses. "I think Kevin Costner is very attractive." Hence: bottoms.

Yet Nihei's true fascination manifests. When a zombie woman shows up, lean and mostly unmutated in a little black dress, her cheekbones are good mostly for detailing how her teeth come out when Zoichi blows open her skinny head. When the girl Zoichi seeks appears, walking in a skirt, it's mainly much the better for tracing the luxurious stretching and splitting of a nude leg torn open by a (talking) motorcycle's tires, and then the recombination of its bloody strips and dancing tendons into a filmy new whole. Better hop into that bear suit, kid - it's a short life for the old flesh. ***

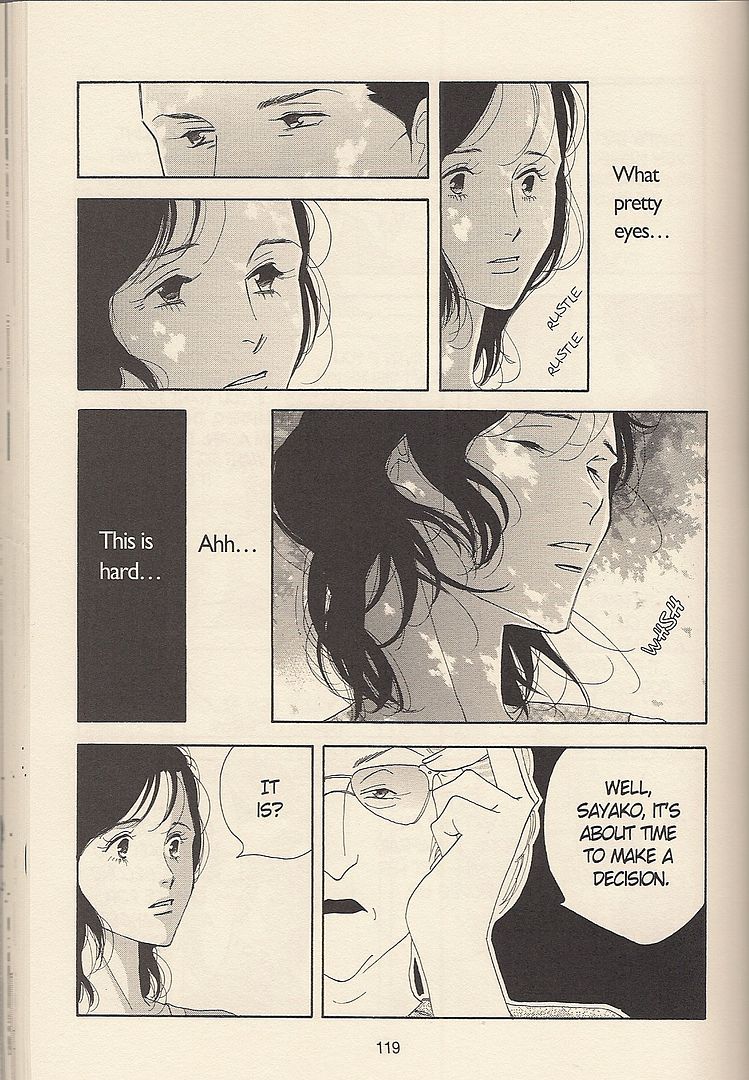

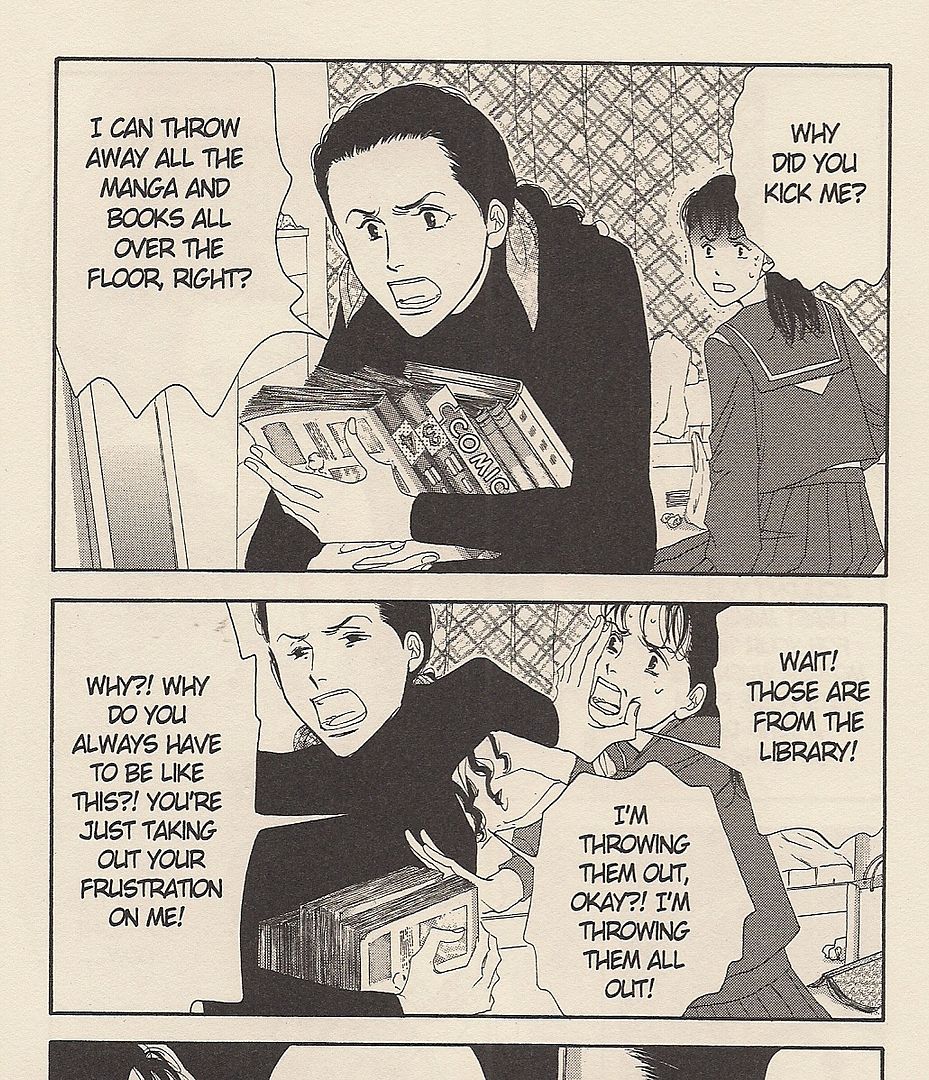

All My Darling Daughters: So, this girl walks into her teacher's office and starts taking off her clothes. She keeps repeating "It's all right" as the flummoxed lecturer urges her to stop, eventually trying to run away when she lifts up her bra. Despite this, he concedes that he likes the girl's breasts, causing her to tear up. She pins him against a bookshelf and demands that he let her go down on him or else she'll yell. He relents -- even though the girl is weird and her hair is oily and sticky -- much to the chagrin of his circle of acquaintances at dinner later on. Yet the girl is among the only ones in his class that seems to listen to him at all; even he considers some of his lectures to be boring. After a subsequent encounter, he offers the girl coffee, which she frantically insists he cannot do, although she tells him he's kind. The teacher idly imagines that he'd accept a more beautiful student's advances anytime. The girl, however, insists that the two of them should not have sex, because it's too good for her; and sex is for the female partner's benefit, while blowjobs are what a man likes best. He smiles when he sees her dutifully copying his words in class. She tells him later that she'd die if he only looked at her face when they're together, and that she used to be embarrassed by her big breasts but accepted them after she learned guys like them; her ex-boyfriends told her that her breasts were her only asset, though she insists they were great guys, because they came to her apartment and ate her food and accepted her presents. She says she likes him better. He admits he's starting to like her, and a friend tells him to return to where it started to go wrong. The next time they're together, he tells her not to go down on him; she cried, but her offers her tickets for them to see a movie. They embrace, and she tells him he's too good for her. In class, he reprimands her for coming in late, and the boy sitting next to her calls her a slowpoke and an ugly bitch. She grins at him as he looks away. "I hope she finds a guy who's a little better than I am." The teacher smiles. Comics?

Well shit, of course it's comics. Not long ago, folks would've called it 'literary' comics, and while that might have raised annoying qualms about imposing prose publishing's literary-genre dichotomy on a different art form -- in that a literary comic could simply be like 'literature' in the sense of being like prose writing itself -- it would nonetheless signal some form of thematic or formalist ambition on the part of various North American comics, albeit at a time when possibly any departure from genre apparatus could be construed as just that.

But comics have grown a lot in the past decade, and the old labels don't stick so well. Case in point: Fumi Yoshinaga, doujinshi-making fan turned pro, the widely-admired creator of the workplace dramedy Antique Bakery and the ongoing alternate history serial Ōoku: The Inner Chambers. This is her newest English release, hailing from 2003 in Japan, a suite of five interconnected stories, one of which I've synopsized above in a way that doesn't leave it too dissimilar to something out of, say, Optic Nerve, Adrian Tomine's quintessential literary comic, which, particularly in its later issues, always struck me as far more cinematographic in its ice-carved observational visuals than anything else. Er, should I mention Raymond Carver?

Prose is not always to be trusted, though, particularly when the prose writer's chief qualification is his blogspot account. What quickly leaps out from Yoshinaga's story is something a plot synopsis cannot capture: how the artist's handling of such potentially risible subject matter is inseparable from her use of the most time-honored aspects of manga iconography. Sweatdrops, booming sound effects, wacky cartoon faces, tiny balloonless dialogue asides - the gang's all here, if not as blatantly so as in youth manga. Still, they are the operations of a mangaka working in a relaxed idiom, a detailed comics language so fully hammered into place by decades of usage in a mass medium that they needn't be questioned. The purpose of Chibi-like cartoon faces are easy to understand (someone is losing their cool), so why not use them in a painful story about a teacher and his student? Because people won't take you seriously? Because you need to look like something else?

Manga may not be the most seriously considered art form in Japan, but it's understood enough that its toolbox doesn't need to be emptied to meet some threshold burden for adult consideration. It's like this: when Jaime Hernandez uses zany cartoon effects dating back to before Dan Decarlo, it's Jaime Hernandez being Jaime Hernandez; when Fumi Yoshinaga does it, it's manga being manga.

Another crucial difference: North American comics don't have a tradition of perfectly GOOD dramas like this to draw from. Currently, they have a small niche capable of selling drama as literature, without the distinctions that mark prose literature, or a limited means of presenting drama as an accessory to genre mechanics.

The beauty of manga is that drama can be simply drama, which, oddly enough, allows for less fussy access to certain literary qualities -- psychological depth, social inquiry, etc. -- though some might claim a more direct comparison to television drama; indeed, Yoshinaga is no stranger to that terrain, in that Antique Bakery was adapted into both live-action and animated television series in Japan, in addition to a feature film in South Korea. This might be a product of comparative serialization, though; certainly most of the television comparisons I hear regarding North American works surround superhero comics, the last big holdout of monthly or weekly chapters around here.

What Yoshinaga's work lacks is interaction with the comics form beyond that of the relaxed idiom. I doubt most non-devotees could even pick her artwork out of a lineup, it's so placidly observant of developed manga values, although a likable blockiness to certain obstinate characters' faces becomes noticeable over the course of the book; certainly she can put together attractive page designs, as evidenced above by the interplay between tones and blocking and those narration-only panels for... special... emphasis.

All of this is directly communicative, however - Yoshinaga is just not a fancy storyteller, rarely attempting even basic dissonance between words and pictures, except for comedic effect. It could be the tide of critical thought is turning, and that as drama becomes more commonplace in North American comics -- hardly guaranteed, given the precarious state of the market -- formalism might yet emerge as the new easy-reading shorthand for 'ambitious' funnies; last year's darling, Asterios Polyp, would obviously fit that bill. I haven't read every manga in the world, but I can't imagine a work like Mazzucchelli's coming out of Japan; maybe my imagination is limited, but it could be that the conditions necessary to conceive of such an obsessive metaphorical outlay just don't exist with manga, where even 'art' comics tend to study movement, like Yuichi Yokoyama's, or play with perspectives or drawing styles, a la Shintaro Kago or the heta-uma artists, or swing a hard fist at societal conditions, as did some of the older gekiga.

You don't need to fulfill any of these criteria to make an effective comic, much in the way you don't need to appear on critics' Top 10 lists to be good. The point I'm getting at is that the transformation of North American comics' makeup will probably cause a shift in how comics are analyzed qualitatively, and it's unassuming books like this that'll raise the biggest questions for readers disinclined to let nationality serve as their co-pilot. Yoshinaga remains upfront, like literature also can. As a writer, she typically has her characters flatly state their minds, confessing to or confiding in one another to move the plot, laughing and crying. She draws superb tears; there's these two pages with a little kid waking up sick, crying and spitting and puking, and there's a world of pain in that, one of the simplest ways comics can charge you up by being what they are.

The stories of All My Darling Daughters aren't very tightly connected -- the characters are all somehow friends or relations of each other, if sometimes tenuously -- although the last one does circle around to compliment the first, and the passage of time is duly conveyed as characters build relationships or get married. All of them concern women struggling with a deterministic world that ensures their relationships are connected to events of the past. Schoolroom slights create lasting tension between a mother and daughter, understandings between friends are informed by teenage vows for the future; probably the most complex aspect of the book is its title, indicating a particular parental concern, a love that Yoshinaga's manga reveals as potentially stifling.

"She said I was too good for her," says the teacher to his friends. That's a recurring sentiment throughout the book, a summary of the neuroses bedeviling Yoshinaga's characters. From this union of aching, across the book as a whole, we can understand the student in that story, even while the artist maintains the male's perspective (the only one of the book) throughout. She is young, and she might find her way out of the trap, although the only characters to really take control of their lives are prompted by one mother's life-threatening disease, thereby signalling a daughter to do the same.

Well, there is another character that undergoes a big change: a young woman who seems to care for everyone, yet never manages a romantic relationship. She's the star of the book's longest and most troublesome story, illustrative of Yoshinaga reaching too far, working with the fairly sophomoric notion of falling in love as potentially cruel discrimination between people as its thematic axis, then ungainly dressing it with allusions to the early 20th century struggles of Japanese leftists and the teachings of Christ, after which a perfectly logical and still faintly silly conclusion is reached.

This character is the counterpoint to Yoshinaga's mother and daughter, a person that can't stand the vagaries of romantic love and thus cuts herself off entirely from mainstream society. It's tempting to read this as revealing of the artist's own position, more adept with smartly observing domestic interactions than grappling with headier stuff; she does seem to want after something different, given this false start's inclusion, and the vastly expanded scope of Ōoku. We may be coming into a time where the new critical biases will demand more, and maybe in a way that Yoshinaga's straight-shot art cannot provide.

Yet maybe the nurturing of calm drama will spark its own nuanced appreciation, and readings will spread outward. Just having a book like this glide across bookstore shelves like it's just manga shows how much the years can change comics, more pliable than Yoshinaga's drawn families and nervous lovers for sure.