"People Come Here For Their Holidays." NOT COMICS! PROSE! Sometimes They Probably Aren't Going To Win Any Awards From The UK Tourist Board!

/What could be better than War Comics? Western comics! But what’s better than Western comics? Why it's surely when I don’t talk about comics at all, and start banging on about some book like I even know what the Hell I’m talking about! Truly, we here at The Savage Critics know how to serve your needs. Look, you’re probably going on holiday, so why not let a complete stranger recommend a really upsetting, but very well-written book? Dettol©® won’t help with this boo-boo, because this? This isn’t just violence, this is…GBH!

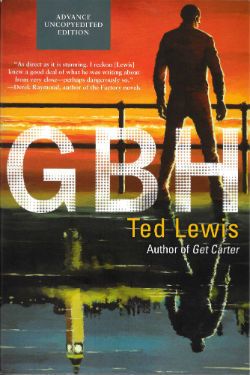

Anyway, this… GBH By Ted Lewis SOHO CRIME (Soho Press, Inc), h/b, £19.99 (2015)

As all connoisseurs of thatch-cheeked 1970s Brit-crime authors know, the very great Ted Lewis popped his clogs in 1982 so what we actually have here is a 2015 reprint of his final, sublimely unpleasant novel from 1980. This edition is ballyhooed as its first publication in America, so I thought I’d better let America know it was out, and what America has let itself in for. Then America can run out and buy it and tuck into the magic of Ted Lewis. Don’t make me feel like I’ve wasted my time here, America! I know you’re out there, America! I can hear you breathing.

First up, even if you don’t realise it you’re probably aware of Ted Lewis’ work from JACK’S RETURN HOME (1970) which was filmed in 1971 as “Get Carter” by Mike “Flash Gordon” Hodges. Everyone’s seen that one, and if they haven’t, well, they just aren’t trying and those people need to up their game; just like the poor in Cameron’s Britain. Word on the street is that it was also filmed Blaxploitation style(?) by George Armitage in 1972 as “Hit Man” starring Bernie Casey and Pam Grier. I haven’t seen that one, but I imagine it’s…something. In 2000 another movie called “Get Carter” appeared and I did see that one; it starred Sylvester “F.I.S.T” Stallone and it was…nothing. As remakes go it was like Blackpool Tower is to the Eiffel Tower. And I mean a plastic souvenir Blackpool Tower that’s fallen behind the radiator in that tat and crap shop; the one next to the fortune teller’s with the picture of Madame Zsa Zsa shaking Sid Little’s hand in the window. So successful was the 1971 movie that the novel was renamed thereafter, and even today Hodges’ movie remains an unsettlingly accurate visual record of a time and place best left gone. Due to its surface wit and style “Get Carter” is frequently perceived as a stylish lad flick, but it is in fact the deeply unpleasant story of a vile man who is quite happy dishing shit out but reacts quite badly when some of it splashes on him. There were two print sequels (JACK CARTER’S LAW (1974) and JACK CARTER AND THE MAFIA PIGEON (1977)) and while the quality decreases as the titles lengthen, neither are quite as pointless as the end of the original might lead you to believe. They are a good time, but not a great time, basically. From what I’ve read (7 of his 9 novels) Ted Lewis never actually wrote a wholly bad book as such and, even better, he wrote a couple of real corkers. GET CARTER being one and GBH being t’other.

GBH is often referred to as Lewis’ “lost masterpiece”; over here (in the UK; the clue’s in my name) it’s only seen print in 1980 and 1994, and in paperback at that. So you are being truly singled out for special attention, America. Don’t throw this back in Soho Press’ face! Anyway, “lost” means no one bought it, I guess, because in the 10 years since GET CARTER Lewis had written some good books but hadn’t had a run of consistent crackers like that one everyone liked, so he’d probably slipped out of the public eye somewhat. Also, drinking. Unfortunately there aren’t any hard and fast rules about booze and creativity; some authors thrive on it but, let’s face it, most only think they do. Largely because they are drunk and their senses are impaired, obviously. After five pints even a ceaseless self-loather like me thinks he’s fucking marvellous, so Christ alone knows what happens in writers’ heads, modest folk that they often be. Anyway, it was his liver to do with what he would. Where the booze paid off (that price – Lewis died at 42. Ker-ching! Beat that Hot UKDeals!) was in a pretty honest portrayal of it, particularly on these pages. Like many a man in a hard-boiled yarn George Fowler sucks the booze down like it’s going out of fashion. Unlike most men in hard-boiled yarns the liquor isn’t used to enhance his manliness (and by proxy that of the (mostly male) audience) but rather ends up unmanning him. George Fowler gets very drunk indeed and the man who wrote George Fowler knew what it was like to get very drunk indeed. Getting very drunk indeed doesn’t do anyone any favours; fact. And getting very drunk indeed is the last thing a man in George Fowler’s position needs. George Fowler needs his wits about him. Because George Fowler is trapped in Mablethorpe. Out of season.

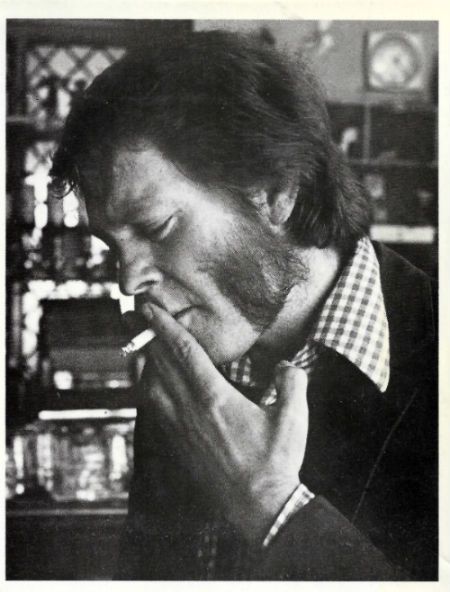

Uncredited photo of Ted Lewis from the back cover of JACK CARTER's LAW.

Uncredited photo of Ted Lewis from the back cover of JACK CARTER's LAW.

See that probably fell a bit flat because America probably isn’t as up on Mablethorpe as it expects the rest of the world to be on, say, Portland. (No, me neither.) So, Mablethorpe is a British seaside resort; a loose but highly centralised collection of shops, hotels, bars, bright lights and fast, thrillingly rickety rides which clings to the coast purely to soak up cash off visiting inlanders during what we laughingly refer to here as Summer. Things have probably changed by now, but back when the book was written (and is set) the British seaside’s charms were more of an exercise in collective wishful thinking than an actuality. Mablethorpe! Where dreams come alive! No one has ever said that. Cheap and cheerful was the order of the day back then, British seaside wise, but we didn’t know any better so we made do. Donkey rides! Postcards of toothbrush tashed husbands leering at ladies melons! Chips trod in vomit A sea too brown for comfort, and too cold to breach! Proper holidays they were. Out of season things were even less fun, with just the sea sullenly remaining but now even browner and colder; a vast turd consommé. The suicide rate in such places probably challenged that of dentists. And Lewis beautifully evokes this drab Purgatory Fowler has exiled himself to, from the awful architecture beneath the perpetually overcast sky to the snippy, chippy malcontents who fill the hours until the brief salvation of the next Summer with booze and backbiting. Fowler stands out amongst them as a sophisticate because Fowler is from The Smoke (i.e. London) and the attention his novelty attracts distracts him from his problems, but because of his problems attention’s the last thing he needs.

Fowler’s problems are back in The Smoke and he’s not overly keen for them to appear here in The Sea. When the book opens we know he has some problems, set-backs if you will, but not what they are. In a series of alternating chapters (The Sea, The Smoke, etc) we find them out as these twin narratives reveal Fowler’s twin losses; first that of his lifestyle and then, perhaps, that of his sanity. Or maybe his sanity’s already flown the coop and the final loss will somewhat more final in nature. Hard to tell with a bloke like George, sanity wise. Now, Jack Carter’s a crap but George Fowler is a monster. Of course, like all good monsters George thinks he perfectly normal, so it’s a clever move to tell the tale (mostly) from his POV. And then we did this, and then we did that, says George , all matter of fact, all low heart rate and slow eye-blink, and then the pieces come together in your mind and you choke back a bit of sick, but you can see George is wondering what all the fuss is about, of course, he continues, after that we had to clean up, and you wonder where the door is, but Ted Lewis has locked it behind him, and it’s just you and George now. And then the lights go off.

George is such a deep, dark pit of shit in fact that it’s entirely due to the titanic level of skill Lewis applies throughout that this reader could not only bear the big shitter longer than a page but even, every now and again, caught themselves actually rooting for him. Sure, I felt dirty but I admired the trick. George is a nasty man in a nasty business but he sees neither as such; he’s just a man and business is, well, business. And we get to know George’s business intimately as the book progresses, and while business may be good for him it is also very, very bad for others. Actually, it’s bad for him as well but he can’t see that. Lewis was always good at showing men arrogant in their belief that they were untouched by the things that damaged others, and then detailing the slow explosion of their unravelling when this belief evaporated like Scotch Mist. (Which is a drink; get me?) That’s only a piece of the parting gift Ted Lewis gave us here, as GBH also provides a convincing depiction of the underworld of the time, with its nasty antics and corrupt symbiosis between villains, filth and hacks and a good old wallow in the abhorrent brutality of a life lived in crime without once glamourising it. Some people (men, mostly) come away from GET CARTER liking Jack, but I can’t see anyone coming away from GBH liking George. It doesn’t mean you won’t feel for him though, because Ted Lewis’ parting shot is to convince us that even evil can love; but it’s still evil for all that. VERY GOOD!

Evil might well love but it gives short shrift to - COMICS!!!