Tucker Proves He Is Incapable Of Sincerity, Thinking: Post One Of One

/![]() I'm a simple man, that should be apparent. I prefer my Passion to be in a Cove, my Bedtime to be packed with Stories, and my Hotel's to be nearby some Erotica. So when Mr. Wolk fired off the "step up to the plate, ye lazy jackals" missive, I thought I'd respond by denying the Critics its Savage-ry, and provide a bit of the "Good Stuff", i.e., stuff I actually find enjoyable. In other words, this is "too many words that say too little" surrounding the old "look at sumthing kewl" comic book blog post. If this was a Pile, I'd tell you to Buy. (Two of three are out of print though, which is a bit of a scumbag move.)

I'm a simple man, that should be apparent. I prefer my Passion to be in a Cove, my Bedtime to be packed with Stories, and my Hotel's to be nearby some Erotica. So when Mr. Wolk fired off the "step up to the plate, ye lazy jackals" missive, I thought I'd respond by denying the Critics its Savage-ry, and provide a bit of the "Good Stuff", i.e., stuff I actually find enjoyable. In other words, this is "too many words that say too little" surrounding the old "look at sumthing kewl" comic book blog post. If this was a Pile, I'd tell you to Buy. (Two of three are out of print though, which is a bit of a scumbag move.)

Yes, there's something after the jump.

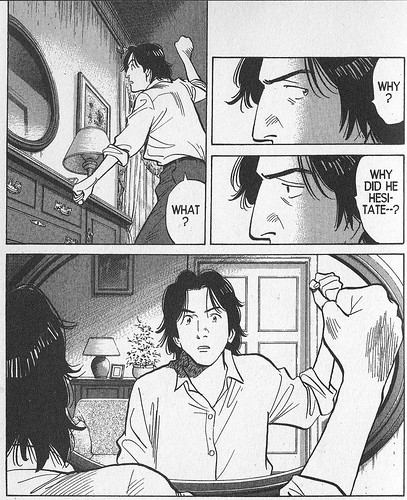

Monster vol 5, by Naoki Urasawa

Naoki Urasawa's Monster goes on a bit longer than necessary, but it's still an All Around GOOD in my book. And while Monster's conclusion includes a violent showdown that greatly pleases me, where men shoot men through chairs while occasionally throwing each other guns in the rain, the portion that stands out in memory is a quieter one that takes place in the fifth volume. It begins here, with Inspector Lunge (the Gerard to Kenzo Tenma's Kimble) examining a murder scene.

Twenty pages later, Tenma arrives at the same scene. Going through the same motions as Lunge, he also reaches the same conclusion, explaining Lunge's "hm" from earlier, and thus cementing the two's relationship that continues until the story's end. Tenma wants the truth. Lunge just wants Tenma. See, somebody died in this room--Tenma thought it was the man he's after, and Lunge thought the same.

Twenty pages later, Tenma arrives at the same scene. Going through the same motions as Lunge, he also reaches the same conclusion, explaining Lunge's "hm" from earlier, and thus cementing the two's relationship that continues until the story's end. Tenma wants the truth. Lunge just wants Tenma. See, somebody died in this room--Tenma thought it was the man he's after, and Lunge thought the same.

They are both wrong.

They are both wrong.

In Tenma's case, that means he has to move, that he has to run. In Lunge's case, that means he's got to choose between truth and obsession. In a way, I spent the remainder of the series feeling like it was Lunge's choice--to focus on catching Tenma, despite the facts--to be a major part of why Tenma is able to remain as focused as he does. There's multiple portions of Monster where Tenma's goal of catching up with Johann (the ultimate villain of the story) is postponed longer than truly necessary. When he can stop and play good Samaritan, he does. When he can slow down and hide out in jail, he does. While Johann's evil schemes ultimately bring Tenma and Lunge to the 18th volume's final conclusion, Tenma's obsession is never as pure as Lunge's, so constantly at odds with his exhausted self-preservation, his fear of how things must end. Lunge, on the other hand, never moves on. He will catch the man he's after, and if it turns out that the man he's after isn't guilty, he'll decide where to go after that. From a meaner viewpoint, that's part because Lunge is never really defined too deeply--he's so much the dogged Terminator that he's even given an almost supernatural memory (one that is depicted by Urasawa as being controlled and accessed by the character typing his fingers in the air)--but that's not too unusual in a story this genre-simple. Without a Lunge to chase him, to force him to discover and expose the truth, Tenma has only to depend on his misplaced feeling of responsibility. Considering how many years pass, it's not hard to imagine that Tenma--a character that Urasawa endows with more realistic emotion than any other in Monster--would eventually give up, feeling he'd tried his best.

I guess Urasawa could've just had him repeat "With great power..." over and over and over and over again, but I think they frown on that in Japan. (I've never been!)

Domu: A Child's Dream, by Katsuhiro Otomo

One of the other comics that I've fallen head over heels with recently is the third volume of Domu: A Child's Dream. The first two volumes (serialized by Dark Horse in 1995) aren't bad, but it's when Everything Goes The Fuck Down in volume three that keeps sticking with me lately. Take a look at this:

She doesn't deserve that, if that matters to you. Neither does this guy, who dies just trying to help.

She doesn't deserve that, if that matters to you. Neither does this guy, who dies just trying to help.

Domu's a pretty straightforward thriller--a couple of telekinetics go to war with each other in a gigantic apartment complex. Otomo spends the majority of the third volume tracing the carnage of their initial, vicious battle, which leaves a healthy portion of the apartment (and its tenants) destroyed. But then he flips it on the reader, with a short "pick up the pieces" interlude. After that little fake-out, the battle continues--only this time, the little girl is prepared for her elderly nemesis. The two sit--her on a swing, him on a park bench--and have a staring contest.

Domu's a pretty straightforward thriller--a couple of telekinetics go to war with each other in a gigantic apartment complex. Otomo spends the majority of the third volume tracing the carnage of their initial, vicious battle, which leaves a healthy portion of the apartment (and its tenants) destroyed. But then he flips it on the reader, with a short "pick up the pieces" interlude. After that little fake-out, the battle continues--only this time, the little girl is prepared for her elderly nemesis. The two sit--her on a swing, him on a park bench--and have a staring contest.

Neither speak, ignoring an "urgh" in the final moments, and with only one exception, none of the bystanders realize what's happening. It's a testament to Otomo's skill that the panels move the way they do--cutting back and forth, the viewpoint going up and down, with little bits of unrelated dialog spitting their way into the frames, accelerating and defining the rate at which the action is occurring. Little details--the way in which tiny shadows appear under pebbles as they race above the ground, a fragment of something slicing across the only onlooker's face--define the actual "action" surrounding the quiet center of the piece, the beating heart: a little girl with a determined (albeit blank) look on her face as she finishes the ugly job of exterminating a crazed killer. As conclusions go, it's EXCELLENT.

Neither speak, ignoring an "urgh" in the final moments, and with only one exception, none of the bystanders realize what's happening. It's a testament to Otomo's skill that the panels move the way they do--cutting back and forth, the viewpoint going up and down, with little bits of unrelated dialog spitting their way into the frames, accelerating and defining the rate at which the action is occurring. Little details--the way in which tiny shadows appear under pebbles as they race above the ground, a fragment of something slicing across the only onlooker's face--define the actual "action" surrounding the quiet center of the piece, the beating heart: a little girl with a determined (albeit blank) look on her face as she finishes the ugly job of exterminating a crazed killer. As conclusions go, it's EXCELLENT.

Another thing I like is punchlines, which you aren't supposed to ruin, but hey: this next one is from a few years ago and I don't care.

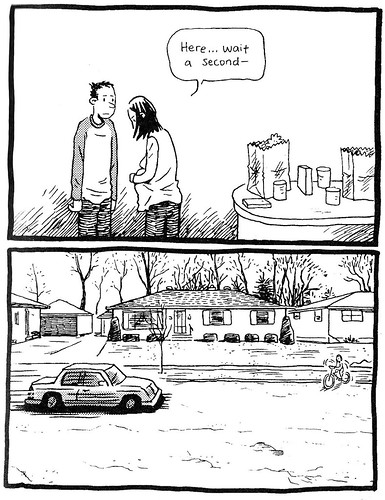

"The Groceries", by Kevin Huizenga

This story is from Or Else # 2, when Glenn and Wendy are unpacking groceries and daydreaming/fantasizing about their future child. Glenn's fantasy involves him getting too little sleep and eventually teaching the child to ride a bike. It's affectionate and brief, and Glenn is only broken from it when Wendy glances over at him and says "What's wrong with you? Come over here and help me." After he describes his thoughts, Wendy daydreams of a more boisterous, verbal future, one that concludes with the frightening image of a bowl being knocked off its high perch, falling directly towards the head of their child. Before you see the tragedy occur, Huizenga cuts to this drawing.

Then, when Wendy describes the dream to Glenn, Huizenga separates the concluding sentence, with Wendy's "And it falls but you catch it before it hits her" appearing on the next page.

Then, when Wendy describes the dream to Glenn, Huizenga separates the concluding sentence, with Wendy's "And it falls but you catch it before it hits her" appearing on the next page.

The thing that gets me with this one: I don't believe that's what Wendy thought. It's not that she's explicitly lying to hide a gory conclusion, but that she aborted the fantasy at the moment of nasty, and then chose to make up a hero ending so as not to draw Glenn into darkness. Glenn seems to be the more sensitive one in the Ganges household--the obsessive one, the one more likely to stay up late over-thinking stuff (as he's currently doing in Ganges #1-3), and Wendy probably knows that she's better off not fueling the crazy. (Of course, Glenn begins obsessing despite her "you saved the day" ending, questioning whether he should move the bowl or not, mentioning that it's an antique, suggesting eBay, rethinking the conclusion of his own fantasy, with a car heading towards the kid--it's not difficult to imagine that, if Wendy had described the bowl braining the tyke, Glenn would've started...I don't know, crying, something like that.)

And that's what makes the joke--which, up until this point, has been pretty well disguised, so clever.

She ain't even pregnant. It's just a melon, which they're eating in the next panel.

She ain't even pregnant. It's just a melon, which they're eating in the next panel.

Of course, few comics retain their humor when their pacing is broken up on the computer screen--it's understandable that this doesn't neccessarily work in scan-and-talk, but it's still a decent encapsulation of what I find so likable about Huizenga's work. Jog described his feelings about Ganges like this:

Of course, few comics retain their humor when their pacing is broken up on the computer screen--it's understandable that this doesn't neccessarily work in scan-and-talk, but it's still a decent encapsulation of what I find so likable about Huizenga's work. Jog described his feelings about Ganges like this:

I can agree with that, and I'd include much of Or Else in that as well. It's not what Huizenga's saying that makes his work so unique, so special--it's how he's saying it. That's the most generic thing one could say about the man's work, but therein lies the rub: it doesn't make it any less true. Here, it's not the drawings, but the pacing--the way pages separate dialog, the blankness of an expression described by the emptiness of a panel--that make the work stand beyond what is, at its most basic, another indy comic about a happy couple going about the mundane necessities. Maybe it's because I'm getting older/shithead-ier, but it's the subtlety that I'm getting into these days. Hell, I used to think this was the coolest part of Batman: Year One.

Now, I like that Mazzucchelli indicates Gordon's ass-peep with a tiny little line.

Now, I like that Mazzucchelli indicates Gordon's ass-peep with a tiny little line.

See it?

See it?

Oh, JIM. You are a CAD.

Oh, JIM. You are a CAD.