Obsolescence & Model Kits: Jeff Looks at FC: Superman Beyond #1 and G-Mo in the DCU

/![]() I remember when I was a kid being entranced with model kits. It was a different time then, back before semi-autistic engineers could make themselves rich with their penchant for elegant complexity: instead of writing computer code, they wrote tactical charts for historical wargames, assembled model kits of cars, ships, jets, and rockets (and, occasionally, monsters and robots), and crafted massive model train sets in garages and basements. Painstakingly, they assembled private landscapes--usually based on an actual historic train route--stipling mounds of carved foam to create textured boulders; studying photographs to create detail accurate train yards; rigging lighting; recreating timetables. Until finally, the engineer was done: he'd remade a corner of the world to scale. It looked perfect, ran smoothly, and made you ache to look at it--because it was devoid of people. I never felt so sad as when I looked at a perfectly constructed model train set.

I remember when I was a kid being entranced with model kits. It was a different time then, back before semi-autistic engineers could make themselves rich with their penchant for elegant complexity: instead of writing computer code, they wrote tactical charts for historical wargames, assembled model kits of cars, ships, jets, and rockets (and, occasionally, monsters and robots), and crafted massive model train sets in garages and basements. Painstakingly, they assembled private landscapes--usually based on an actual historic train route--stipling mounds of carved foam to create textured boulders; studying photographs to create detail accurate train yards; rigging lighting; recreating timetables. Until finally, the engineer was done: he'd remade a corner of the world to scale. It looked perfect, ran smoothly, and made you ache to look at it--because it was devoid of people. I never felt so sad as when I looked at a perfectly constructed model train set.

Whereas model trains made me sad, the model kits filled me with frustration. Even the simplest was well beyond the scope of my clumsy fingers and lazy soul. You had to snap and clip plastic parts off a manufactured lattice, then sand the barb from where the part connected with a lattice, glue the parts together, wait, paint them, wait, apply decals, construct the diorama in which to...I'll be honest, I never got past clipping the third or fourth part off the lattice. Part of it--most of it, actually--was shameful laziness, but some of it was the suspiciousness with which I regarded the model makers. After all, if I was supposed to do all that, why didn't I just carve the god-damned thing out of soap? It seemed to me they were taking advantage of my desires (and the abundance of industrial grade plastic at their disposal), turning a tidy profit by promising a completed product for which I would do the majority of the work.

I realized just yesterday, that those feelings of frustration and shame and suspiciousness, are my constant companions when reading most of Grant Morrison's work for the last five or six months. At some point, Morrison stopped writing stories, and began churning out mental model kits of stories, which only work if you take the time to snip them apart, study the instructions, and assemble them yourself.

[More in this vein, alas, behind the cut.]

I have theories as to why Morrison has turned down this path. Many, many, theories. The least generous theory is that Morrison is a brilliant manic-depressive who can cogitate like a motherfucker in his manic stage, falls back on his tropes when he hits his depressive phase (or just stops producing altogether), and is smart enough to make it all sound like it was one organic plan after the fact. So, for example, you get something like "New X-Men" that generates tons of new ideas in the beginning, hits a bad patch where it's all about Mutantbolik and his flying saucer girlfriend, then sprints through a "widescreen" finale (followed by a rushed two part epilogue that jams in all the stuff he never got around to).

A more generous theory is that while Morrison has the mind of a formalist, he's got the heart of an anarchist. If a storyline of his takes too long, he can't help but think of ways to fuck it up and make it more interesting, even if those new ideas invalidate the groundwork he laid. I'm thinking here, again, of his New X-Men storyline, but also The Invisibles, which mutated as it went along, ending far from where it started. Because Morrison constantly layers in allusions that work on multiple levels, it's easy for him to claim victory in the end by suggesting the level that didn't satisfy wasn't the one you weren't supposed to be paying attention to. In some cases (Sea Guy or The Filth, let's say), I believe that's absolutely the case and in some (Xorn, and the New X-Men run being characterized by Morrison as a conscious deconstruction of how the franchise defeats the author), I believe that's absolutely Morrison talking out his lipstick-smeared butthole.

But most generous of all my theories is that G-Mo has constructed a way to promote the work on the Internet that doesn't involve running a forum, or having a Twitter account, or keeping track of his Myspace friends: the individual issues aren't stories jammed with easter eggs, but easter egg hunts cordoned off by a ribbon of plot. The stories themselves aren't particularly difficult, but tracking the details of the plot through the thicket of detail can be, which is where all the online annotations come in handy. As Abhay pointed out in his brilliant recreation of a Marvel panel at SDCC, readers today don't really have any idea how a story works--they only want to know what will happen to the characters they follow, hitting Newsarama day after day to get the spoilers, with no real interest in the story that ostensibly explains exactly that. And companies and creators play along, spoiling stories to lesser and greater degrees so as to build buzz and heat from the resulting discussions and outcries. Morrison's brilliant and daring twist is to construct stories so people will hit the Internet not to discuss what will happen, but to figure out what is happening. Next to the way Mark Millar promotes himself on the Internet, it looks downright elegant.

Under this theory, the fact my enjoyment of Final Crisis didn't really start until I read Douglas' annotations, or that my enjoyment of Batman R.I.P. derives entirely from commentary of fine internet including (but not limited to) Mindless Ones, Funnybook Babylon, and our own critics and commenters, is all part of the plan. Indeed, even though I picked up the majority of the references in Final Crisis: Superman Beyond #1 covered by David Uzumeri's annotations, his willingness to analyze Morrison's intentions on the fly (particularly during that five page Monitor origin sequence) gave me a greater appreciation of the work, and even helped me uncover new layers of interpretation.

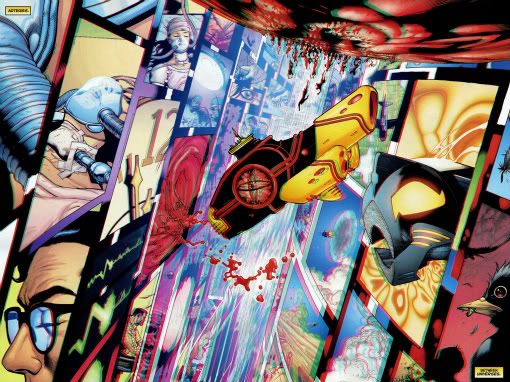

However, while they gave me the tools to appreciate the work, they didn't give me the tools to enjoy it which suggests that something has gone terribly wrong, either with me or this devious master plan I've capriciously attributed to the book's writer. Honestly, I'd be more willing to attribute this to me if I wasn't reading a comic book where five supermen board a yellow submarine to sail through the metaverse--and one of those supermen is a drugged-out Dr. Manhattan analogue. As Graeme McMillan so frequently says to me when discussing comics, "Come on! How can you not love that?" Honestly, it's such a direct descendant to batshit Steve Gerber stories from the '70s, I can see how I could love it. I should love this book.

However, while they gave me the tools to appreciate the work, they didn't give me the tools to enjoy it which suggests that something has gone terribly wrong, either with me or this devious master plan I've capriciously attributed to the book's writer. Honestly, I'd be more willing to attribute this to me if I wasn't reading a comic book where five supermen board a yellow submarine to sail through the metaverse--and one of those supermen is a drugged-out Dr. Manhattan analogue. As Graeme McMillan so frequently says to me when discussing comics, "Come on! How can you not love that?" Honestly, it's such a direct descendant to batshit Steve Gerber stories from the '70s, I can see how I could love it. I should love this book.

And yet, I don't. I mean, I think I'd give it a high OK or something (particularly if you have stereoscopic vision and can take advantage of the 3-D glasses, which I don't and can't) because it's pretty and cool and brings back stuff from Morrison's Animal Man run.

And yet.... I dunno. It could be the model kit factor, where I'm a little frustrated that for $4.50 I get so much frickin' event and so little story. There's not really what you would call much of a plot revealed in all these pretty pages: Superman gets recruited by Zillo Valla (although no one uses that name until the last four or five pages and, at least in the case of Superman, it's not clear how he learns it), they board the Ultima Thule, things go wrong, they end up in Limbo, people make arbitrary decisions--honestly, at this point, it's not really too different from a Friday the 13th movie. You've got the bullying jock (Ultraman), the kind-hearted peacemaker (Captain Marvel), the druggie nerd (Quantum Superman) and the kid who dies the first time he has sex (Overman). If the second issue has Superman in a bra and panties running screaming around the perimeter of a lake while being chased by a chainsaw wielding Anti-Monitor, I won't be too surprised.

I don't think it's the model kit factor, in short. I think Morrison has fallen prey to the Model Train set mindset. Everything looks gorgeous, and the detail is planned out to a staggering level, but there aren't any characters in Superman Beyond #1: there are people with names, their basic character and that's all you got. While Morrison has used such deliberate flatness to extraordinarily good effect in All-Star Superman, I find it more disappointing here simply because there's not thirty-plus years of character identification with most of these characters, and the ones for whom there are--Captain Marvel, for example--get about three lines that aren't purely exposition. It's not surprising Morrison uses a musical motif to explain the travel through the metaverses: he's using the characters in this book (and perhaps in his others) like leitmotifs, thematic markers that gain complexity when contrasted with other markers.

It's a very smart way to deal with work-for-hire superheroes--you can't change them or develop them, after all, so half the traditional conception of what makes a story is out the window anyway. But it may be that I find I prefer the illusion of change and development to no development whatsoever, no matter how much room you clear up for phantasmagorical imagery once you chuck that illusion. For example, if Morrison recognizes that the character with the most depth in Superman: Beyond #1 is Merryman, the King of Limbo, he seems unaware of what this might mean. It's not that every character is too delightful to be consigned to Limbo, but that in innumerable universes where everything happens but nothing has any lasting impact, it's really no different to a single space where nothing happens--the former is just prettier than the latter, and it takes a little longer for boredom to set in there. But once it does, it doesn't matter how many times the trains trundle past their scale-model mountains. No one waits near the flickering waxy light of the station for them to arrive, and when the creator leaves the room, it's as if none of it ever happened.