In The Wee Small Hours: Jeff Looks At The Man With The Getaway Face

/Here's a fun fact I learned at Wondercon 2010: Darwyn Cooke is probably the closest thing comics has to a Frank Sinatra. I was with Matt Maxwell on the last day of the Con, we were both getting ready to leave, both of us feeling beat up in different ways and for different reasons, and Matt swung by to say a quick goodbye to Cooke who was over in artist's alley.

I was aware Matt and Cooke knew each other, although I wasn't sure how well—it seemed like a casual friendship, nothing super-tight or anything (although if you know Matt Maxwell, you know the man has his own code of what he'll talk about and what he won't and things have to move in the teeth-pulling direction before he even considers talking about the latter). So what kind of impressed me is that, as Matt waved at Cooke over the throng of people at Cooke's table, Cooke looked over, smiled, exchanged a few words with Matt, seemed very touched Matt had taken a few minutes to stop and then thanked him...and, in doing so, blew Matt a small kiss.

It takes style for one hetero guy to put his fingers to his lips and blow a kiss at another guy and not have it seem, you know, kind of fey. In fact, this came off as pretty much the opposite: it was the ne plus ultra of het masculinity, affectionate but also jokey and even self-mockingly benedictory. When guys in gangster movies grip one another with a meaty hand below the ear and kiss each other on the cheek? It was kind of like that.

In fact it was exactly like that, and it made me think, suddenly, of Frank Sinatra, a guy who'd deliberately battled his way up to the top of the tough guy heap exactly so he could dish out such acts of gentleness and sentiment without getting any grief for it. (Indeed, it's not easy to remember but Sinatra did a ton of work to get himself positioned exactly so: between being the crooner adored by swooning bobby soxers and having a 4-F rating that kept him from military service during WWII, Sinatra in the '40s had been considered one of the great candyasses of the western world.)

I'll be honest with you here—this is the point where I'm supposed to break out my deep, deep knowledge of Sinatra's music and his personal history, do a little bit of the ol' presto-changeo!, and show you exactly how The Chairman of the Board and Darwyn Cooke (The Chairman of the Bristol Board! Start the meme now!) are intriguing mirror images of one another, images made strange by working in such dissimilar media and to such different ends.

Instead, I'm forced to confess my familiarity with Sinatra is, at best, slight and the closest I can come to tying the two men together is exactly the thing that kept Ol' Blue-Eyes at such a distance for mesomething I'll call The Nelson Riddle Factor.

Nelson Riddle was Sinatra's arranger at Capitol in the '50s, precisely the time when Sinatra pulled off his spectacular career resurrection and went from being a facile 4-Fer to tormented tough guy, and I must be the only guy on the planet who finds Riddle's arrangements the epitome of treacle. I can make it through a song of his if I'm at a bar and I've got a beer under me—in fact, I can even make it through two—but anything more than that and I feel like someone is emptying a cement mixer full of honey over me. It is too too—every imperfection is smoothed out, every nuance underscored with a flourish, every string section put to work even if the job could've been done with a solo violin. It's sonic bathos.

It's a testament to Cooke's talent I don't feel the same about his work, frankly. Being familiar with the source material, I enjoyed Cooke's adaptation of The Hunter but I also understood Dan Nadel's stinging critique over at Comics Comics: What Nadel objects to is precisely the Nelson Riddle factor in Cooke's work, the tendency toward excess (or as Nadel memorably puts it, "every room Parker walks into has an Eames chair and a Noguchi table. Every clock is by George Nelson. All the women are outfitted like cheesecake 'dames.'") in adapting a work known for its spareness. It's not the sort of excess those of us who read a ton of superhero comics easily recognize because we're used to bombastic excess, but it's there. Only the mix of Cooke's storytelling chops--the rhythm of the panels on the page--and the original story's killer narrative hook kept The Hunter from becoming torpid.

So I'm relieved—giddy, in fact—that The Man With The Getaway Face flips the script so successfully: Cooke cuts material from the second Parker book and strips it down to a twenty-four page comic book. Sure, it's oversized and mustard-colored, stylized and clearly in love with the milieu, but it's a comic book about Parker getting a new face and scaring up some money by way of an iffy heist he's not in a position to turn down.

Cooke has to make some hard choices here, but the work is all the better for it and it makes the bravura touches really hit home. The first four pages, for example, feature a credit page sequence that dares you not to think of Saul Bass, and two full page-splashes, one of which is an annotated letter. I have no doubt Cooke could come up with an entire graphic novel full of stunners like this but they're quickly swept aside as the book, and Parker, gets down to business in a series of eight and nine-panel pages which use the oversized format to keep things from feeling utterly claustrophobic.

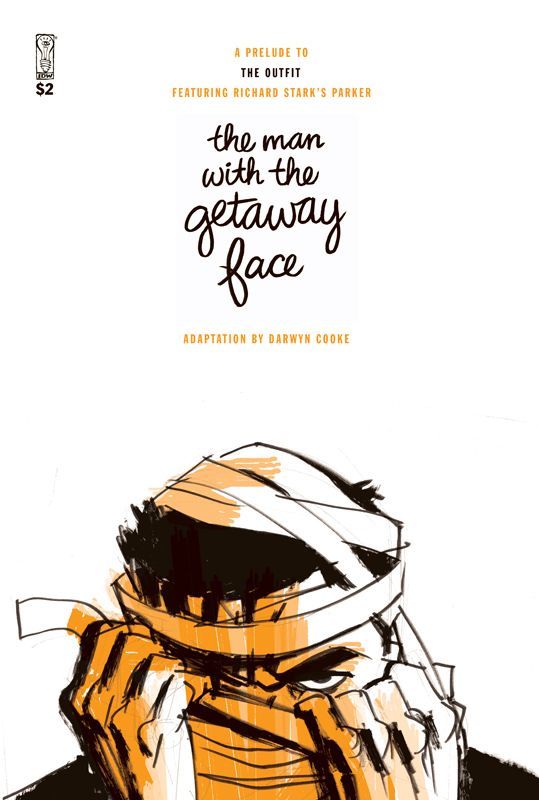

Like the heist presented inside, Cooke's The Man With A Getaway Face is all about planning and timing. Lovely bits that could've been meaty set-pieces get cut to the thinnest slices possible (I'm thinking here of the panel showing just the ten items needed to pull the heist, presented with no explanation whatsoever) and the art moves from stylization into honest god-damned cartooning: Parker has a face that doesn't come together from panel to panel—in one panel, the tip of his left cheek bone escapes his face altogether, and in long shots his head looks like the puzzle piece Curious George swallowed—but that suits the character perfectly (he has just had reconstructive surgery, after all, and it's easy to imagine how raw-boned and unsettlingly malleable his face must now feel) as well as gives the eyes something to linger on. As Graeme pointed out in our recent podcast installment, even the cover is loose, not-right, with the pencil under-sketching on the right hand visible.

We'll have to see if Cooke is going to keep working like this, or if he decided this was just the way The Man With The Getaway Face had to be—loose, speedy, and purposeful—and The Outfit will shift gears once again. Although this story will be included as a prologue to that book, I prefer The Man With The Getaway Face the way you can get it now: oversized, gaudy, and cheap. It's the Sinatra single I never got to hear—experience and talent and impeccable phrasing, all those fucking binding strings finally snipped away—and it's Excellent work, well worth your time and coin.